4. Findings

General observations

Across all three research activities some more general observations of sentencers’ experiences and interactions with the guidelines were captured. These findings do not highlight issues with the usability of the guidelines, but are presented to reflect some of the broader context around how sentencers interact with the guidelines.

Sentencers generally have a relatively positive experience of using the guidelines, though believe it could be improved in some areas

Sentencers are generally satisfied they can locate the information they need to make sentencing decisions. They use the guidelines in their everyday role and so navigating the website feels familiar. This sentiment was expressed by one circuit judge who stated ”[the guidelines are] functional, and [are] accurate and reliable”.

However, they also recognise the usability of the website could be improved. Sentencers identified that improvements to the website could save them valuable time in their roles, ultimately leading to improved efficiency in sentencing. One magistrate reported “I’ve probably got a list of 25 cases to get through…so to put it bluntly, if I spend two minutes or even a minute longer [navigating the website], then that’s half an hour out of my court time. And that’s [equivalent to] two or three cases. So time is of the essence really.”

Unlike judges, magistrates sit on a bench in a group of three. When sitting on a bench, not all magistrates look up the guidelines. However, this depends on the preferences of other magistrates on the bench

When magistrates were sitting on a bench with other magistrates, sometimes only one of them might look up information on the sentencing guidelines. These magistrates then provide this information (usually verbally) to other members of the bench (although it was noted this was not a consistent practice and varied depending on the preferences of other magistrates). In some cases, all magistrates on a bench would look up information in the guidelines.

Magistrates who were presiding justices on a bench (i.e. those who chair the bench and oversee the court’s proceedings) reported they would generally direct one of their ‘wingers’ (i.e. one of the other two magistrates on the bench) to look up the relevant guidelines for a case, while they focused on the evidence being presented. However, they might also have to help other magistrates (particularly newer magistrates who were less familiar with the guidelines) with finding relevant guidelines. They also noted that they, or another ‘winger’, might focus on looking at case information or other resources on the Council’s website (e.g. the fine calculator).

Both magistrates and judges were observed generally interacting with the guidelines in a similar manner.

Sentencers primarily referred to steps 1 and 2 of offence specific guidelines when making sentencing decisions

When making a sentencing decision in court, or when preparing for cases, sentencers (both magistrates and judges) almost always referred to steps 1 and 2 of offence specific guidelines. These steps were seen as the key starting point for their decision-making. “If I’m in the guidelines, it’s because I want to see the starting point and category range” (Magistrate). This is mirrored in the results of the Council’s internal survey), which found that a high proportion of sentencers always referred to steps 1 and 2 of the guidelines, though comparatively fewer referred to the remaining steps on a regular basis.

Sentencers generally considered that it was not critical to refer to steps 3 to 9 in the guidelines every time they made a sentencing decision. The reason they gave was that these steps were generally the same across different offences, and felt they knew how to apply these from memory, particularly if they were familiar with an offence or with an offence specific guideline. For example, sentencers commonly expressed they knew the relevant reductions for a guilty plea, so would not need to refer to step 4 in every case.

Nonetheless, sentencers considered it helpful to have all the steps included within the offence specific guidelines, to help remind them of what they should consider. These steps were considered easily available and accessible for sentencers to check or refresh their understanding of these steps.

Sentencers’ familiarity and confidence with IT influences their experience of the guidelines

The majority of sentencers who participated in virtual usability testing and interviews self-reported being confident using technology. However, during in-person observations and virtual usability testing sessions, the degree of digital literacy users demonstrated when using the guidelines was quite varied. This has implications for their experience of the website.

Sentencers who had higher levels of digital literacy, for example those who had experience working with IT, were less satisfied with the usability of the website. They were also more likely to use an alternative platform to access the guidelines (e.g. UK Court Manager – a website developed by an independent company which provides sentencing information and tools, including the sentencing guidelines). They were able to draw upon their knowledge to identify specific elements of the website that could be changed to improve their user experience.

Sentencers with lower levels of digital literacy tended to be more satisfied with the guidelines. Nonetheless, they still contributed ideas for changes to the website so that it would better meet their needs. Additionally, they experienced barriers to using guidelines as they were either not aware of, or did not have the capacity to utilise, features and functions which were available (e.g. viewing offence specific guidelines in different tabs.) Some sentencers remarked they had learnt new skills just from participating in research activities.

Sentencer age did not appear to be related to levels of confidence with using technology, with sentencers across different age ranges reporting varying levels of familiarity with using technology and digital devices.

Sentencers tend to use laptops to access the guidelines, with some preferring to use two devices, and a small minority preferring to see the guidelines on paper

Whilst most sentencers indicated they used laptops to access the guidelines, some use two devices (e.g. a laptop and an iPad, two separate laptops, or a laptop and mobile phone). This was generally done to allow them to view the guidelines on one screen and the case details on another screen. They appreciated being able to see all the information they needed at once.

A couple of sentencers preferred to work with paper guidelines. Although they still access the website, they do so only to print off the relevant offence specific guidelines before each case. While these sentencers stated they print off the guidelines as needed for each case (and do not keep the printed guidelines), this may pose a risk that they do not refer to the most up-to-date guidelines. This approach is associated with personal preference, but may also be related to users’ confidence in being able to navigate the guidelines using a laptop or other electronic devices.

Magistrates tend to access the guidelines via a shortcut located on the desktop of court laptops, while judges (including district judges) typically have the guidelines bookmarked on their laptop

Sentencers (particularly magistrates) generally use a shortcut icon located on the desktop of court laptops by default. They found this a straightforward way to reach the guidelines. Judges tend to have bookmarked a link to the guidelines on their court-issued laptops.

When using an alternative device (e.g. a personal laptop, smartphone, or iPad), sentencers tended to either login to their eJudiciary account (which provides sentencers with remote access to the judicial intranet system) to access the guidelines or reach the guidelines via a Google search.

These findings echo the results of the Council’s internal survey, which found a majority of respondents reported accessing the digital guidelines using a laptop.

Specific findings and recommendations

The following section outlines the more specific findings and recommendations consolidated from all research activities. This section is structured based on the following research questions for this project addressing the usability and experience of the guidelines.

- Searching for guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines with the current search functionality?

- Using the guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines given the current layout and format of the guidelines?

- Navigating the guidelines: how easy is it for sentencers to navigate different guidelines and additional sentencing resources on the Council’s website?

- Accessing the guidelines: how do sentencers access the guidelines?

- Sentencing with the guidelines: how do sentencers use the guidelines when making sentencing decisions?

BIT have suggested the priority in which recommendations should be implemented, by rating each recommendation. These ratings include:

- high priority recommendations: to address common and critical barriers to sentencers’ usability and experience of the guidelines

- medium priority recommendations: to address substantive barriers to the usability of the guidelines, though these may not be consistently faced by all sentencers

- low priority recommendations: to address issues sentencers consider to be less critical to the usability of the guidelines

Where possible, we have illustrated how recommendations could be implemented. We would also encourage the Council to consider piloting or testing these recommendations with sentencers, prior to fully implementing these recommendations.

A. How easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines with the current search functionality?

Finding A1: the search functionality is not intuitive or easy to use, which takes up sentencers’ time

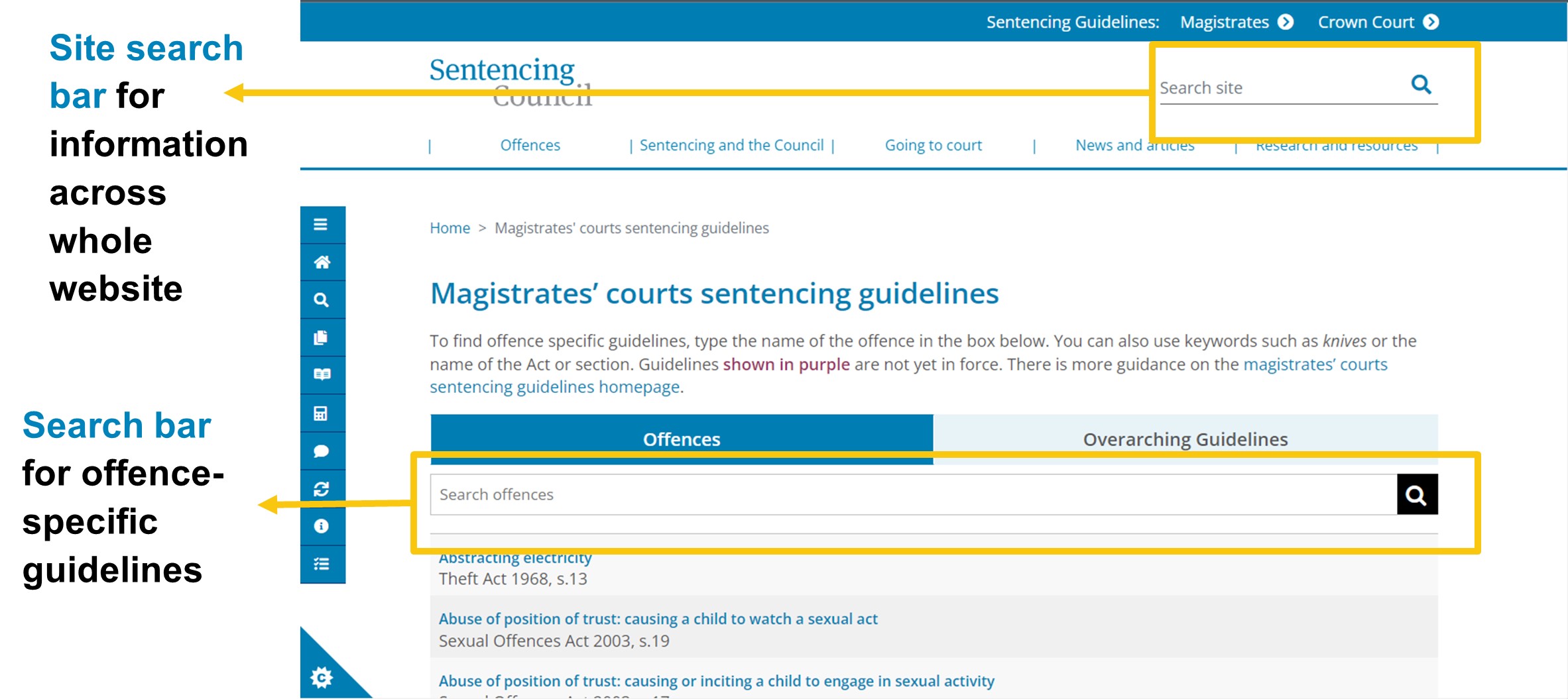

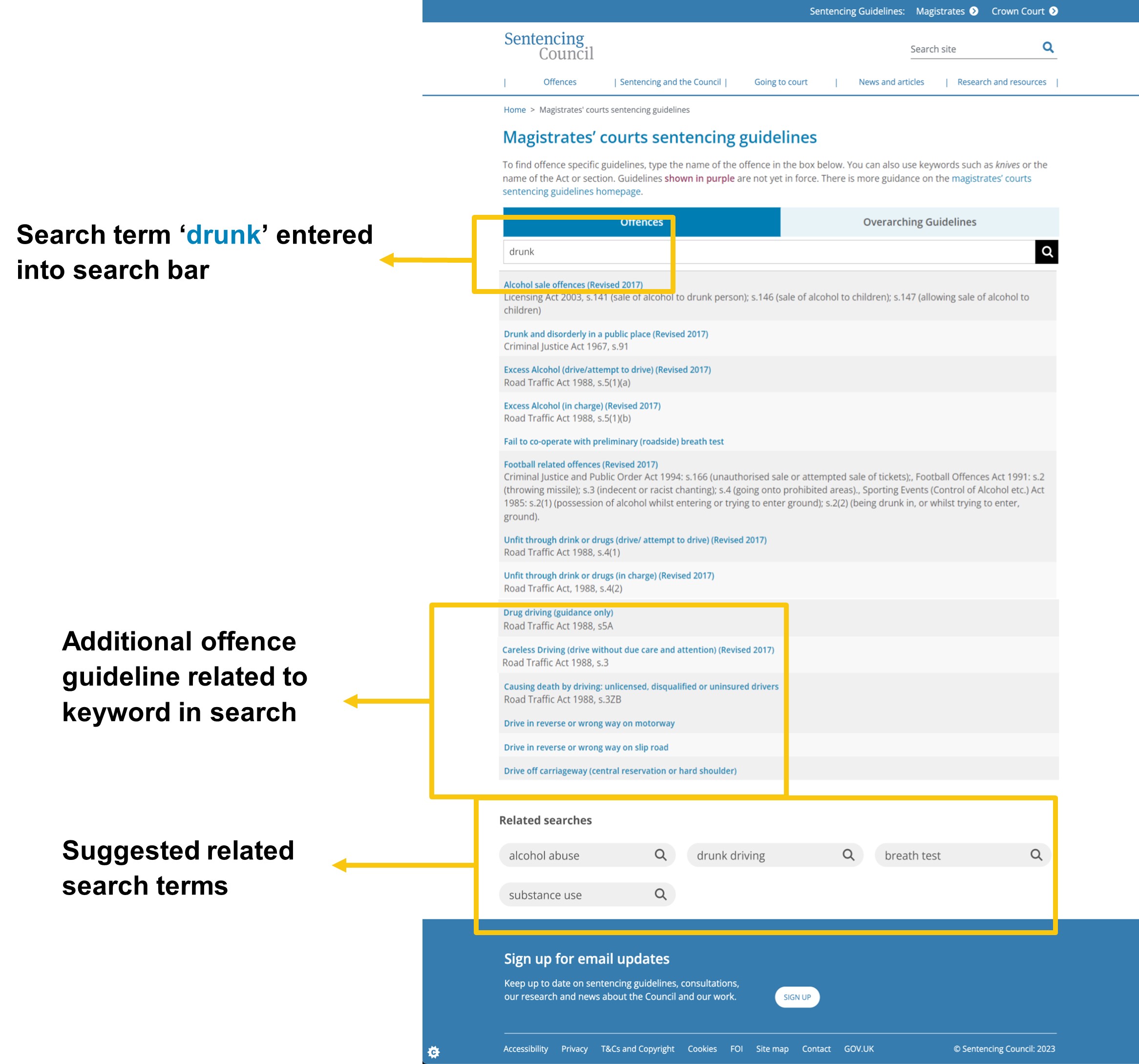

There are currently two different search bars available on the Council’s website. The search bar available on the offence specific guidelines search pages is designed to only search for offence specific guidelines. The site search bar is located in the top-right corner of the Council’s website and enables individuals to search for content across the whole website. These search bars are shown in Figure 4 below. All sentencers were observed only using the search bar in the offence specific guideline landing pages to search for offence specific guidelines.

Figure 4: Image of the magistrates’ court guidelines with the two separate search bars available

Sentencers did not find the search bar in the offence specific guideline landing pages easy to use. Certain keywords were expected to return particular offence specific guidelines – especially when these included either the offence name, the corresponding Act for the offence, or a term commonly used to refer to the offence. However, this often did not provide the results they were expecting. Sentencers reported the search function as being “clunky”, “fiddly”, and “the biggest [downfall]” of the guidelines.

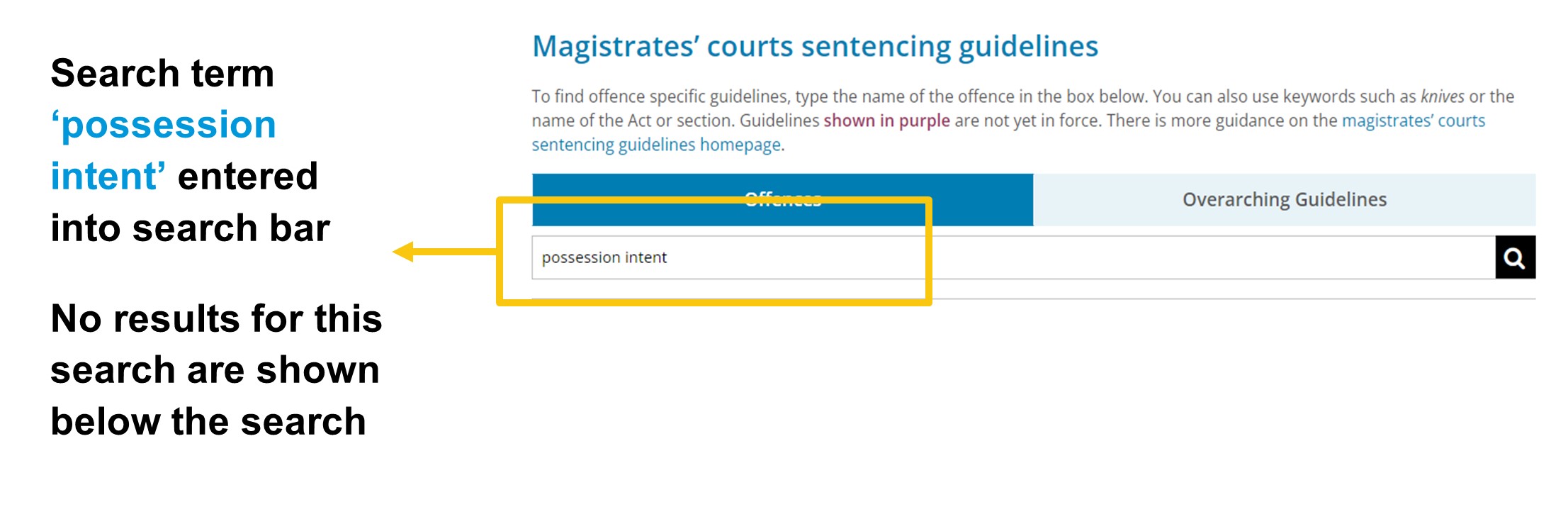

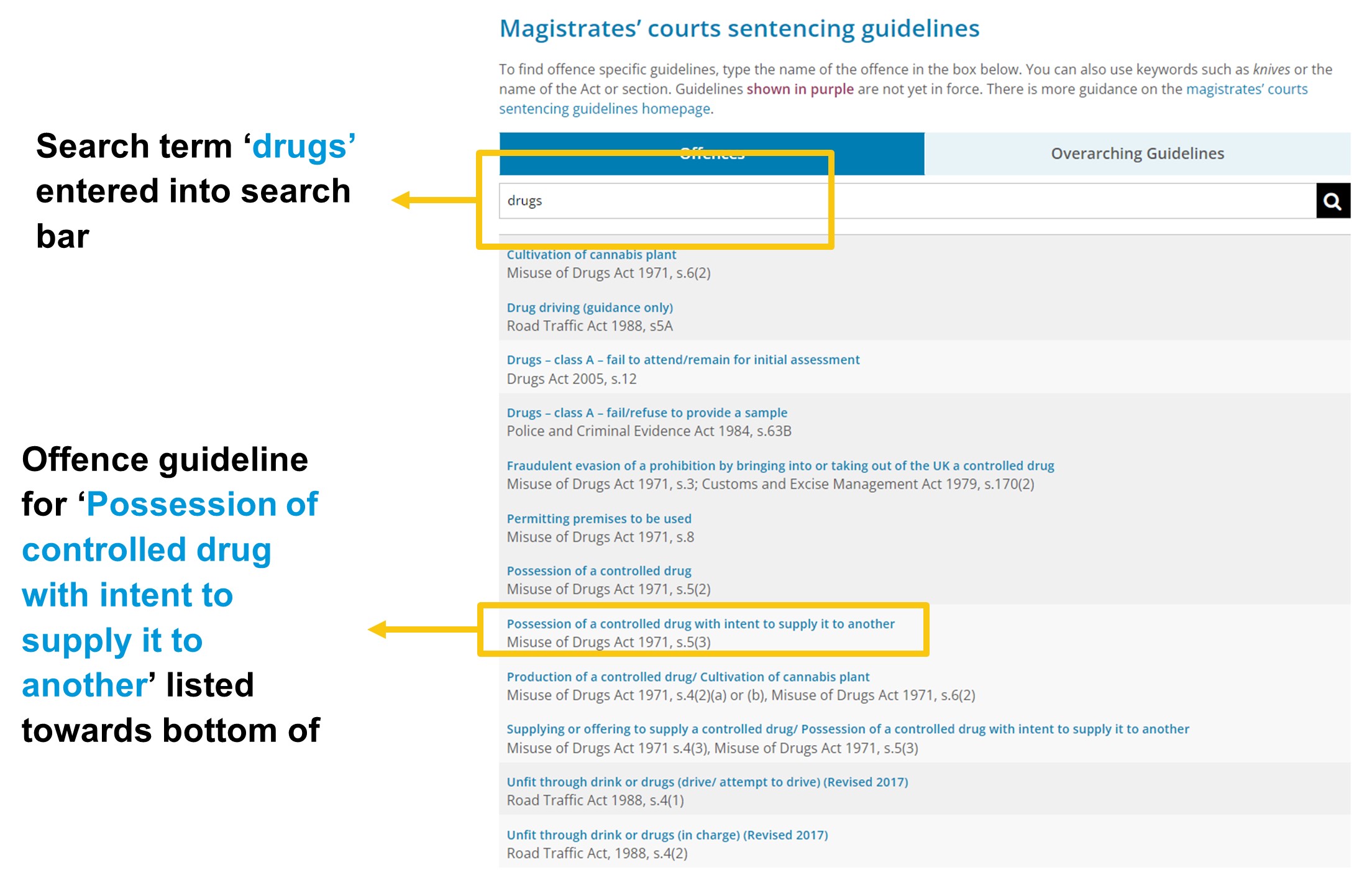

After entering keywords, search results either did not correspond to the keywords, or returned offence specific guidelines related to the keywords, but not the specific guideline sentencers were searching for. On other occasions entering keywords did not return any results at all. As an illustrative example, one sentencer attempted to search for the Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another guideline. The following five search terms were entered, with none of these searches returning the relevant guideline:

- ‘possession intent’

- ‘possession with’

- ‘possession drugs’

- ‘s 5(3)’

- ‘Section 5[space]’

The sentencer located the relevant guideline after entering the search term ‘drugs’. Examples of these search results are shown below.

Figure 5: Search results from magistrates’ court guidelines based on the keywords ‘possession intent’

Figure 6: Search results from magistrates’ court guidelines based on the keyword ‘drugs’

Another sentencer reported avoiding using the search functionality altogether, stating it was easier to scroll through the list of all offence specific guidelines to locate a specific guideline. During virtual usability testing and in-person observation activities, a couple of sentencers were observed using Google to find certain offence specific guidelines.

Sentencers reported the following types of offence specific guidelines, as being difficult to find:

- public order offences

- assault offences

- driving offences

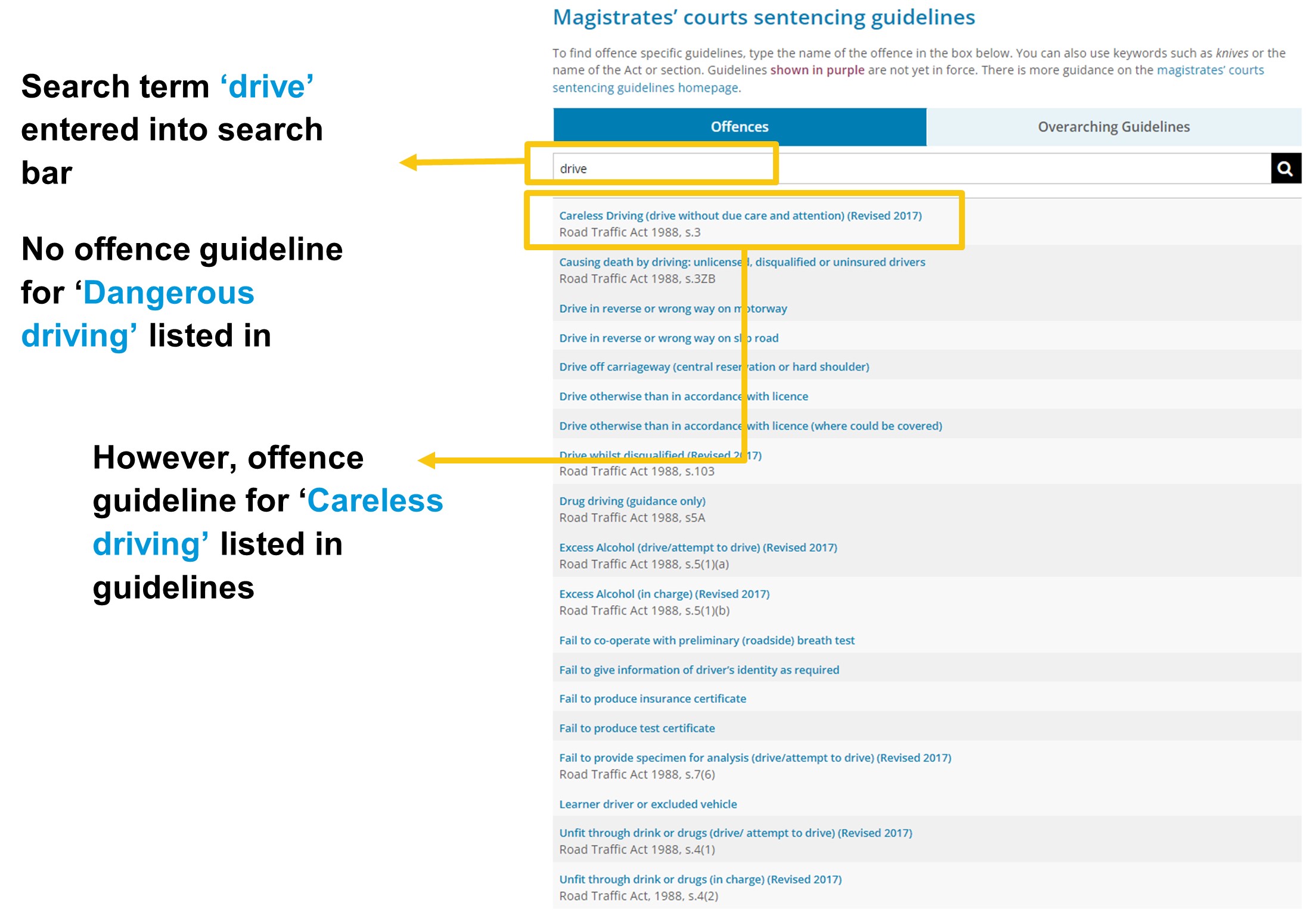

Part of this issue appeared to stem from the lack of consistency in how the search function worked. For example, one sentencer was observed searching for the Dangerous Driving offence specific guideline, and entered the search term ‘drive’. The search results did not list the dangerous driving guideline, though did list the Careless Driving guideline (see Figure 3). The sentencer remarked it seemed like the search function identified guidelines with ‘driving’ in the title. However, this was contradicted by the ‘dangerous driving’ guideline not being included in the search results. Therefore it was unclear to the sentencer how the search function actually worked.

Figure 7: Search results from magistrates’ court guidelines, based on the keyword ‘drive’

The impact of these issues is that it takes longer to find relevant guidelines. Sentencers commonly reported that searching for offence specific guidelines took up additional time. This was a concern when needing to find guidelines quickly in court and was noted by both magistrates and judges. Some sentencers also remarked this could risk not focussing on evidence being presented in court, due to difficulties searching for guidelines. Some sentencers stated that whilst they could pause court proceedings, this was not always practical or feasible as it took away from court time.

During in-person observation sessions, magistrates were also observed taking additional time to help other magistrates search for relevant guidelines – even if they had already found the relevant guidelines themselves.

Not all sentencers reported finding the search function difficult to use. However, this was a minority opinion expressed in this project. Moreover, some of these sentencers had memorised which search terms to enter in order to locate specific offence specific guidelines. “[The] search works well…it’s only a problem when you don’t know what to search [for]” (Magistrate).

Despite difficulties with the search function across the different research activities, all but one sentencer, were (eventually) able to locate the guidelines they wanted to view when undertaking the research exercises. This suggests the search function can technically be used to find offence specific guidelines. However, this currently requires additional time, multiple search attempts, and patience, on the part of sentencers.

Recommendation A1: improve the search functionality for offence specific guidelines with a greater ‘smart searching’ capability.

Priority: high

Refine the search functionality to provide a greater ‘smart searching’ capability, which returns relevant search results, even if the exact search term is not included within these results. To achieve this, the Council should consider adapting the search functionality to include alternative search terminology, partial matches and word stems. These adaptations have been informed by reviewing usability design better practice guides.

Alternative search terminology search results should be responsive to different terms sentencers may use to refer to offences, including less technical or legal terminology. For example the search term ‘marijuana’ should return a result for the Cultivation of a cannabis plant guideline.

The search bar in the offence specific guidelines search page provides results based on search terms for abbreviations of offence names, and the section number of Acts referring to specific offences. These should be monitored and revised on a regular basis to adapt the search functionality to potential changes of offence names and sections of Acts. Moreover, sentencers should be provided with prompts on similar search terms which have been used, or offence names which are related to the search terms being used. This could include showing words similar to the search term below the search bar, or below the search results (see Figure 8 for an example).

Partial matches: search results should be related to the keywords entered, even if there are grammar or spelling errors within the search term. For example, if there are additional spaces entered between, or after, search results should still be presented for that search term (e.g. ‘section 5[space]’ returning results for ‘section 5’). Another example is not using the exact ordering of keywords to provide relevant search results (e.g. both ‘aggravated assault’ and ‘assault aggravated’ should return the Racially/religiously aggravated common assault guideline).

Word stems: search results should be related to both the keywords and its morphological stem (i.e. the keyword without its ending or suffix). As an example, the stem for ‘abuse’ would be ‘abus’. Refining the search result to include this stem would provide results when entering the search terms ‘abusing’ or ‘abused’ (which currently do not provide any results in the search bar – while ‘abuse’ does return results of offence specific guidelines).

The Council could also consider integrating a search analytic capability for the search bar in the offence specific landing pages. This would enable the Council to review search logs and identify common search terms sentencers use, to effectively adapt the search functionality. This search analytic capability would benefit from using geolocation data to obtain search logs from specific geographical areas (e.g. locations of magistrates’ courts and Crown Courts) to review search terms which are likely being entered by sentencers or other relevant stakeholders (e.g. prosecutors and solicitors).

These considerations will improve the user’s experience of the search functionality as it reduces the cognitive load on sentencers when attempting to search for offence specific guidelines. Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental effort people expend when undertaking different tasks. People’s capacity to perform mental work is a limited resource that can be taken up by planning, remembering, worrying, self-control, etc. (Fiske and Taylor, 1991). The current experience of sentencers likely imposes a cognitive load as it requires sentencers to focus their attention on how they can search for certain offence specific guidelines. However high cognitive load has been shown to impair task performance, increase likelihood of quitting unsolvable problems faster, and make more passive choices (Baumeister et al., 1998).

Reducing friction points can help reduce the cognitive load experienced by sentencers. Friction points are small details that make a task slightly more effortful (e.g. an extra mouse click). Whilst seemingly irrelevant, these can make the difference between doing something or avoiding doing it (BIT, 2014). Making the search function more responsive to sentencers’ search queries will help reduce the friction in searching for an offence specific guideline. This makes it easier for sentencers to spend more of their attention on other sentencing related tasks.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Mocked up example of recommendation A1

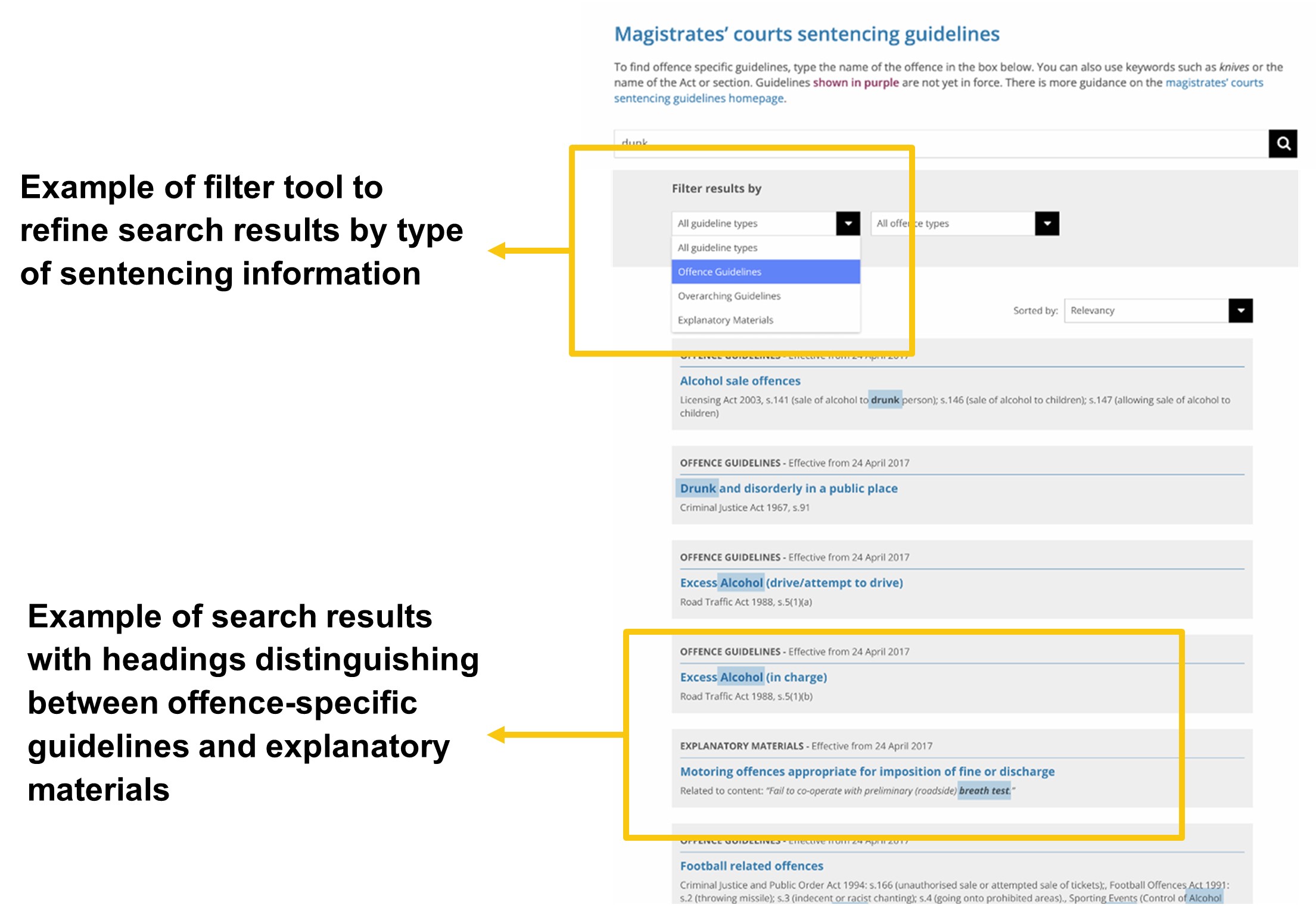

Finding A2: search results are not presented intuitively, which makes it harder to find specific offence specific guidelines

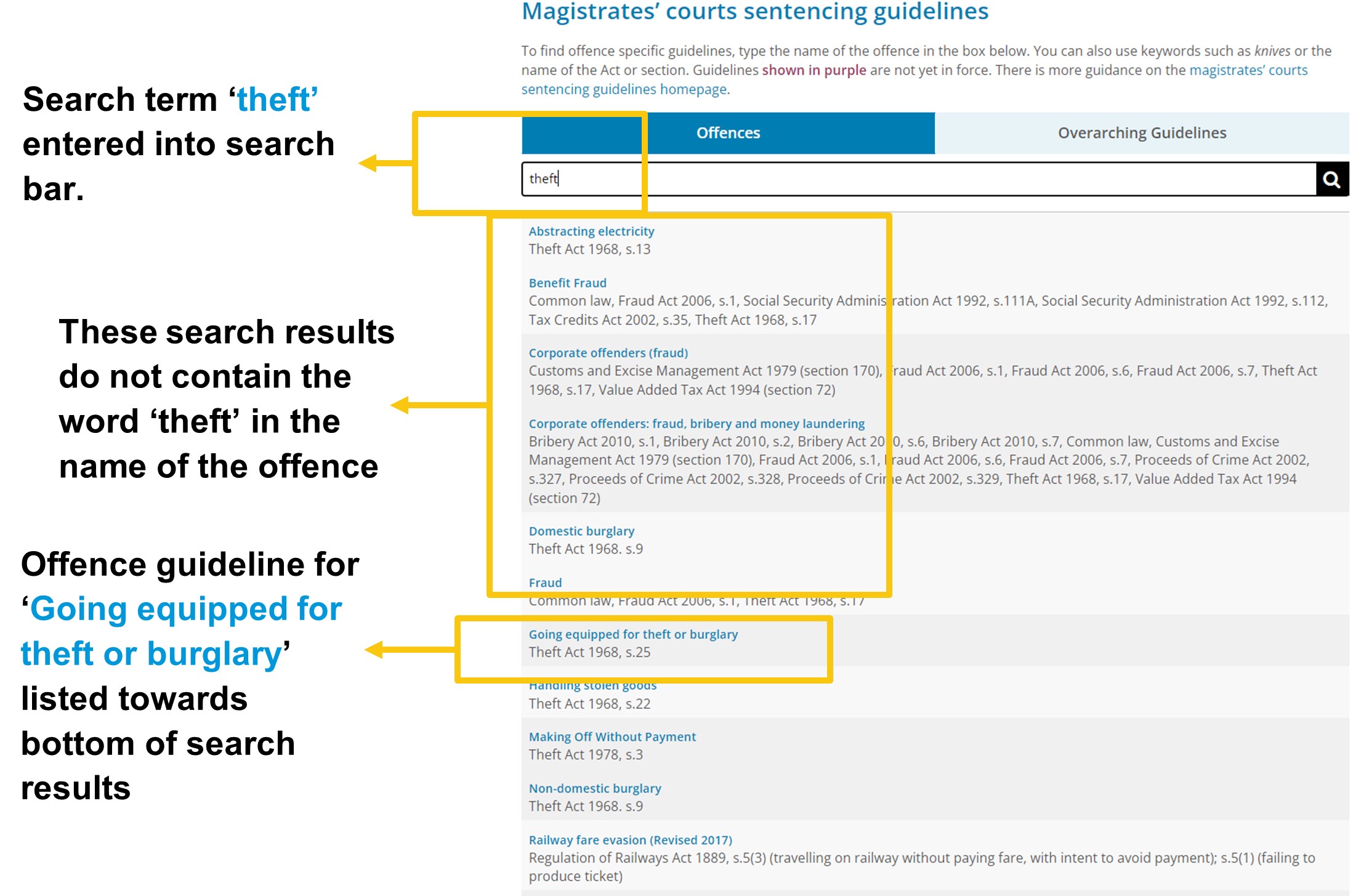

While search results of offence specific guidelines are listed alphabetically, sentencers expressed confusion about the order of search results. They reported that it wasn’t clear if these were listed in order of relevance to the search keywords grouped by certain themes, or grouped by similar Acts. It was not clear to sentencers that results were listed alphabetically, with some expressing they didn’t understand if there was any order to the search results.

As an illustrative example, one sentencer was observed searching for the Going equipped for theft or burglary guideline and entering the search term ‘theft’. The sentencer was surprised that the first six guidelines in the search results did not contain the word ‘theft’ in the offence title (see Figure 9). They expected the intended guideline (‘Going equipped for theft or burglary’) to be higher in the search results. In this case, the other guidelines in the search results included offences from the Theft Act 1968, and other theft-related offences. Therefore, the ordering of these guidelines in the search result list was not intuitive.

Figure 9: Partial search results from magistrates’ court guidelines based on the keyword ‘theft’

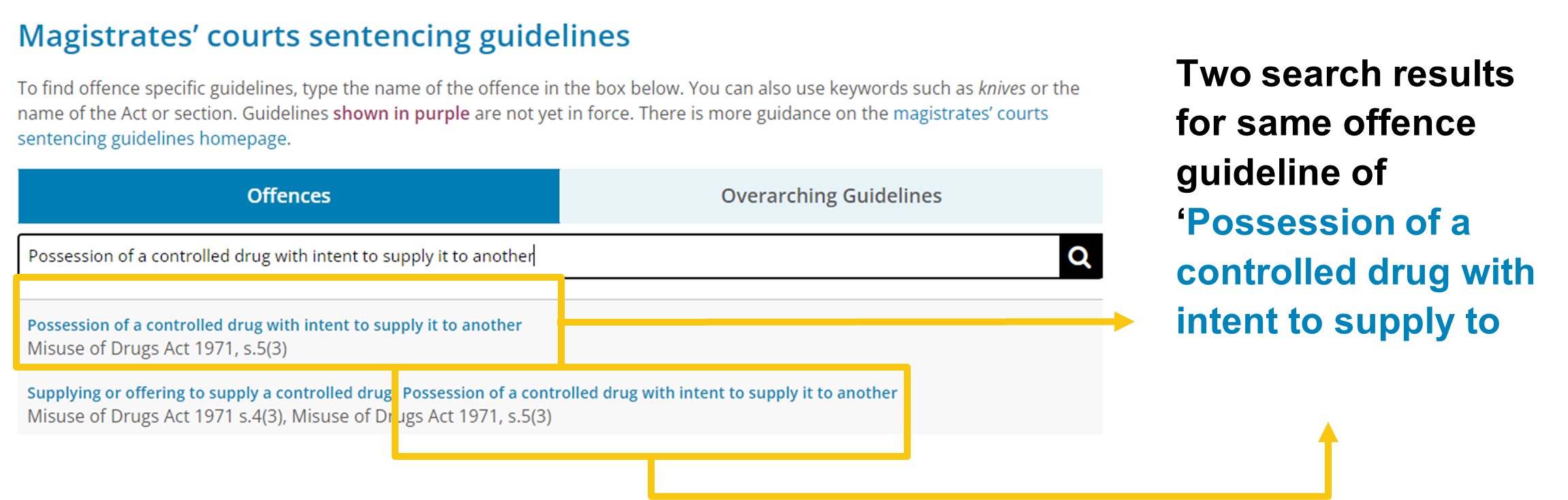

A contributing factor to this issue appeared to be the format and layout of the search results. With the current layout, sentencers were observed scrolling through the search results and missing the offence specific guideline they were looking for. The correct offence specific guideline was found only after having scrolled back and forth through the search results. This indicates the layout of the search results may not be optimally presented to quickly identify relevant guidelines.

Additionally, it was not always clear to sentencers if the guideline for an offence would be listed as a standalone guideline in search results or contained within a guideline for multiple offences. For example, one sentencer noted when searching for the Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another guideline, that there were two separate results for this offence specific guideline (as shown in Figure 10). This also added complexity to understanding how the search results were listed.

Figure 10: Search results based on keywords ‘Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another’

In addition to the time taken by sentencers in making multiple attempts to search for an offence specific guideline, extra time is also required to locate the relevant guideline in the search results. This is especially the case when a large number of search results are listed.

Larger lists of search results were presented when sentencers used broad or generic search terms. While more specific search terms could provide shorter search result lists, the search function did not work well using specific terms. This led to sentencers using more generic search terms, resulting in more search results for them to view.

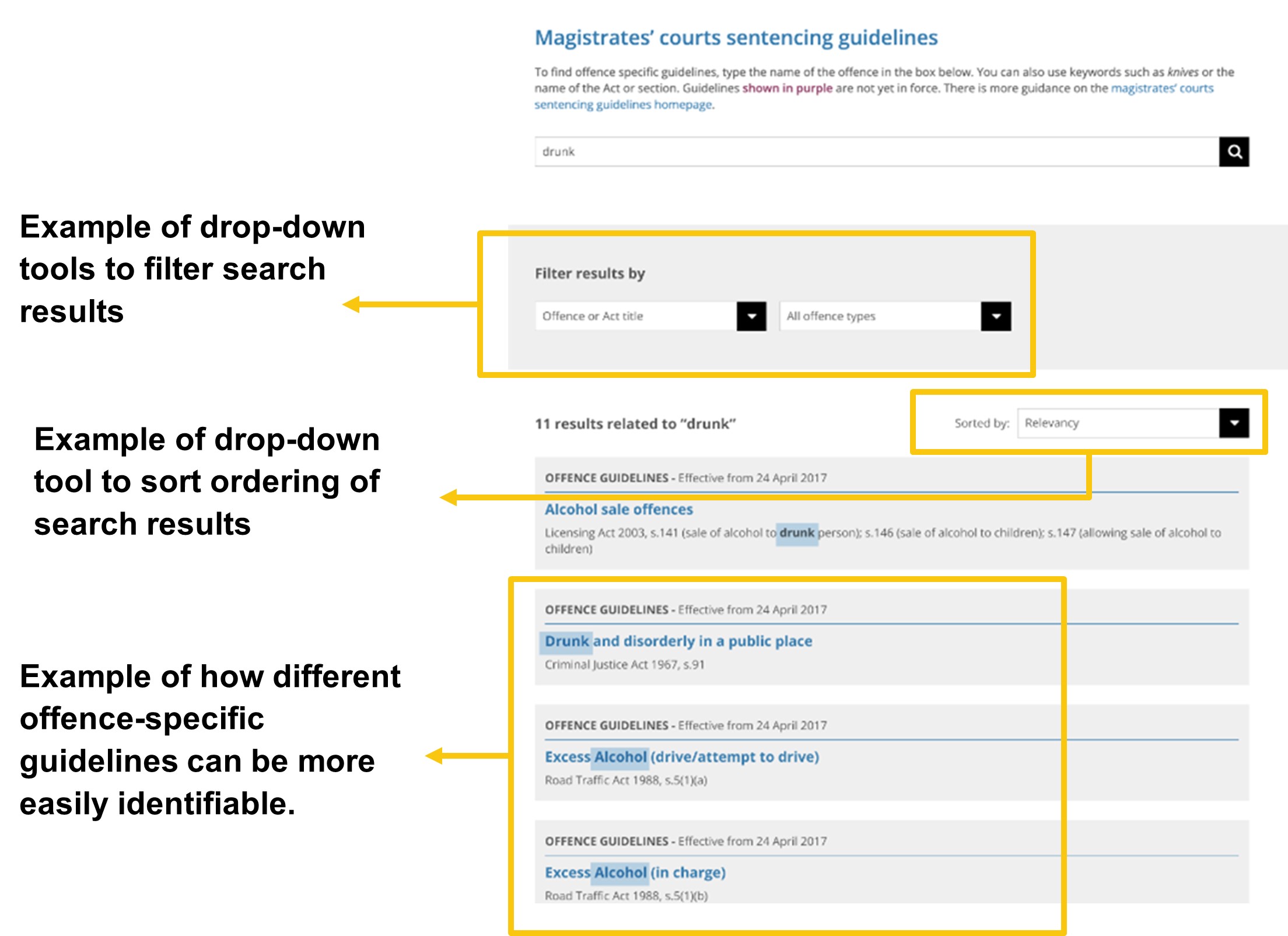

Recommendation A2: refine the order of search results to be presented in order of relevance, and refine the layout of results so sentencers can more easily identify relevant offence specific guidelines.

Priority: high

Search results should be presented in order of relevance – something sentencers expect -with each result being more easily distinguishable from others. Given that most sentencers typically began their search with keywords reflecting the name of offences, the order of search results should be prioritised based on the relevance of keywords within guideline names.

To help make individual search results more easily identifiable, there could be small gaps of white space between each offence specific guideline in the search results. This can help sentencers more easily direct their attention to different search results, to help identify relevant guidelines.

In addition, search results should include highlighted text to help sentencers identify why the results have been listed (e.g. having the search term (or other related terms) highlighted in the search results). Where the search term includes text from content within particular offence specific guidelines (rather than the guideline name), this should also be highlighted within the search results.

Highlighting the search term within the search results makes the results more visually salient, which can help quickly direct sentencers’ attention when viewing the search results (Fisher et al., 1989). This process further helps to reduce the cognitive load sentencers may experience when having to review search results to identify a specific guideline.

Moreover it would be helpful to provide sentencers with the ability to sort and filter search results. This can be achieved by having dropdown boxes, to sort search results by relevance to keywords, or alphabetically by Act or offence name. Providing this functionality can help reduce the potential for choice overload, wherein having too many options can negatively impact people’s motivation to make effective decisions (Lyengar and Lepper, 2000).

As noted in Recommendation A1, the Council could also consider integrating search analytic capabilities for the search bar in the offence specific guideline pages. This could facilitate reviewing search logs for terms entered into the search bar, to identify search terms commonly associated with click-throughs to certain offence specific guidelines. For example, such a review may identify the search term of ‘possession’ is more frequently associated with click-throughs to drug-related offence specific guidelines, rather than for bladed article guidelines. In this case, drug-related offence specific guidelines containing the keyword ‘possession’ should be listed higher in the search results than guidelines for bladed articles which also contain the keyword ‘possession’.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Mocked up example of recommendation A2

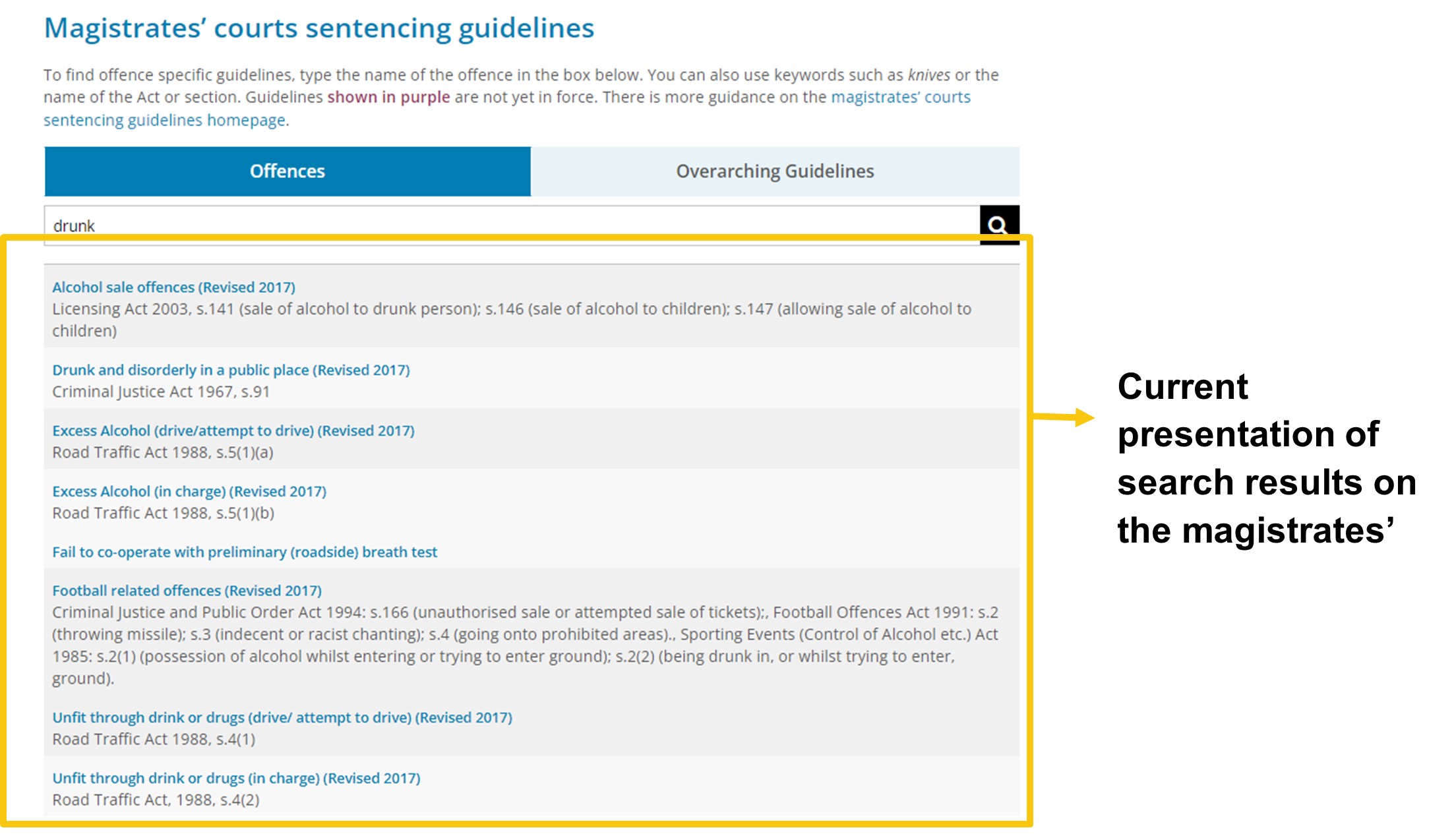

Figure 12: Comparison image of search results from current magistrates’ court guidelines based on the keyword ‘drunk’

Finding A3: the names of offences in sentencers’ court listings do not always match the name of the offence specific guidelines on the Council’s website

Sentencers (especially magistrates) noted this was a common and consistent problem. The wording of offences within court listings were often used as search terms. For example one sentencer stated ‘assault by beating’ was the name of an offence in their court listing. They were observed entering the search term ‘beating’ which provided a result for the Common assault/Racially or religiously aggravated common assault/ Common assault on emergency worker guideline. However ‘assault by beating’ was not listed in the name of this offence specific guideline. Sentencers expected that the names of these offences would be the same as those in offence specific guidelines.

As the name of offences did not always match, this required sentencers to double check whether they were looking at the correct guideline. This typically included checking the section and Act of offence specific guidelines and matching these to the offences noted in court listings.

This resulted in even more time and effort required to locate relevant guidelines. This discrepancy “slows things down”, with one magistrate stating this “causes me issues because you have to make sure everyone is on the same page before you start”. A common feedback point was to have consistency between the names of offences noted in court listings and the offence specific guidelines.

Recommendation A3: provide an easy way to locate the correct offence specific guidelines from the offence names noted in sentencers’ court listings.

Priority: high

Provide hyperlinks within offences noted on (digital) court listings to relevant offence specific guidelines. In general, the names of offences within court listings should be aligned with the names of offences listed on the guidelines.

However, it is acknowledged that court listings are provided through digital platforms by HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) and are not the responsibility of the Council. Nevertheless, the Council should explore opportunities with HMCTS to provide easy to use links to relevant sentencing guidelines from HMCTS digital platforms.

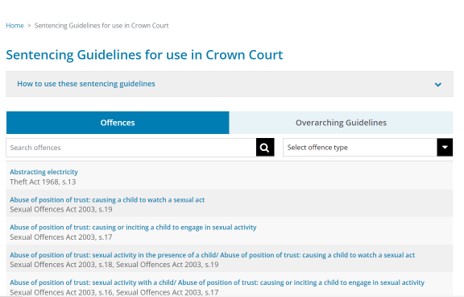

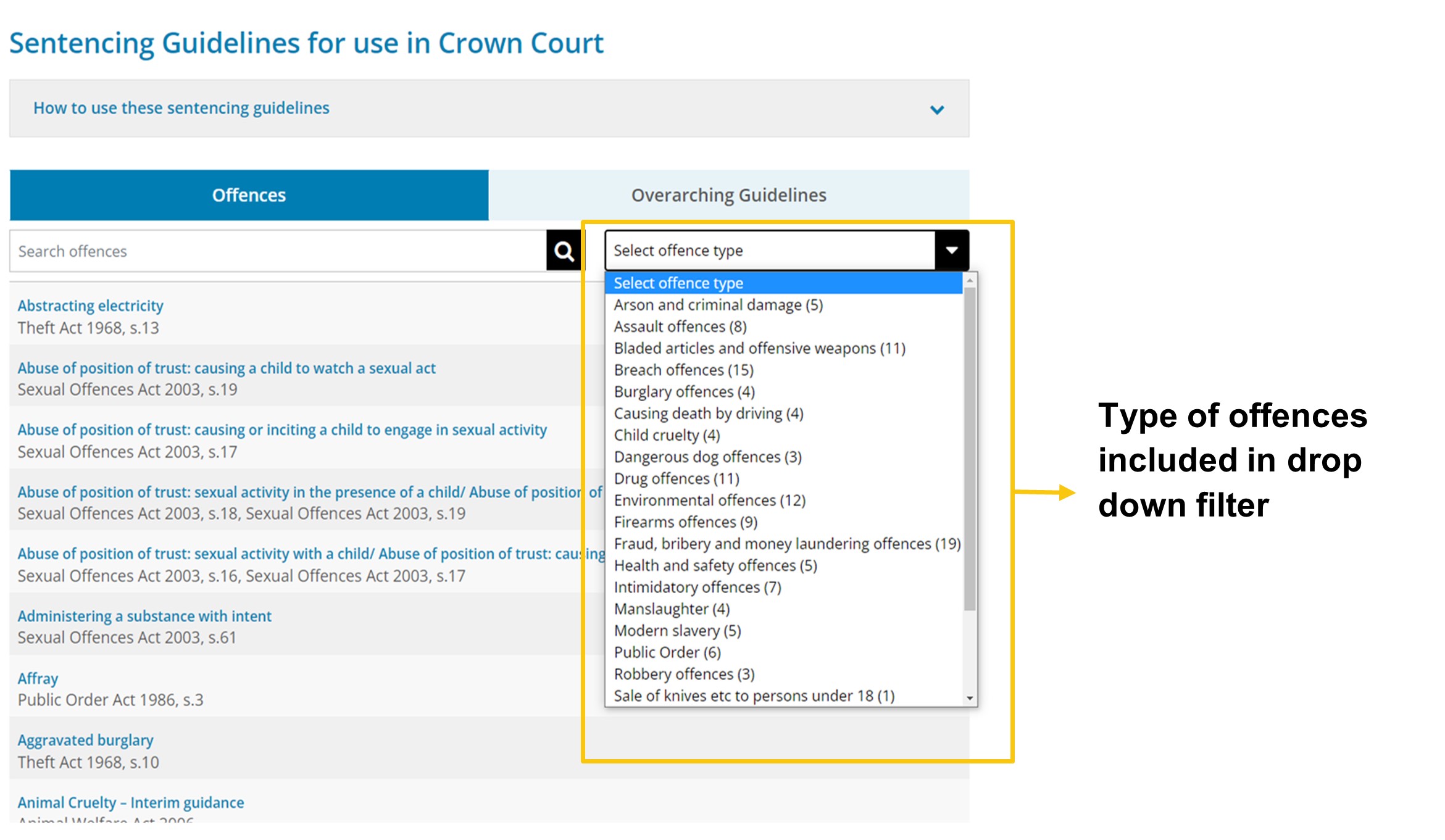

Finding A4: the dropdown filter of offence types in the Crown Court guidelines is useful to search for offence specific guidelines, but isn’t available for the magistrates’ court guidelines

Circuit judges found using the dropdown filter of offence types helpful to search for offence specific guidelines. Indeed, some only used the dropdown offence type filter to search for offence specific guidelines (i.e. they did not enter any search terms into the search bar).

Figure 13: Dropdown filter of offence types in the Crown Court guidelines

Selecting an offence type from the dropdown filter in the Crown Court guidelines typically brings up a relatively short list of offence specific guidelines (usually around or fewer than 10 guidelines). This makes it quick to identify a particular offence specific guideline. The exception to this was the Sexual Offences category, which has 65 offence specific guidelines.

Figure 14: Partial list of offence types included within the dropdown filter in the Crown Court guidelines

Moreover, when an offence type is selected the resulting guidelines are consistently listed in the same order. This makes it easy to remember where certain guidelines are located in the filtered list. Sentencers also noted this was similar to how the paper-based guidelines were structured (i.e. being grouped together by offence type). That structure had also made it easier to remember where certain offences were located in the paper-based guidelines.

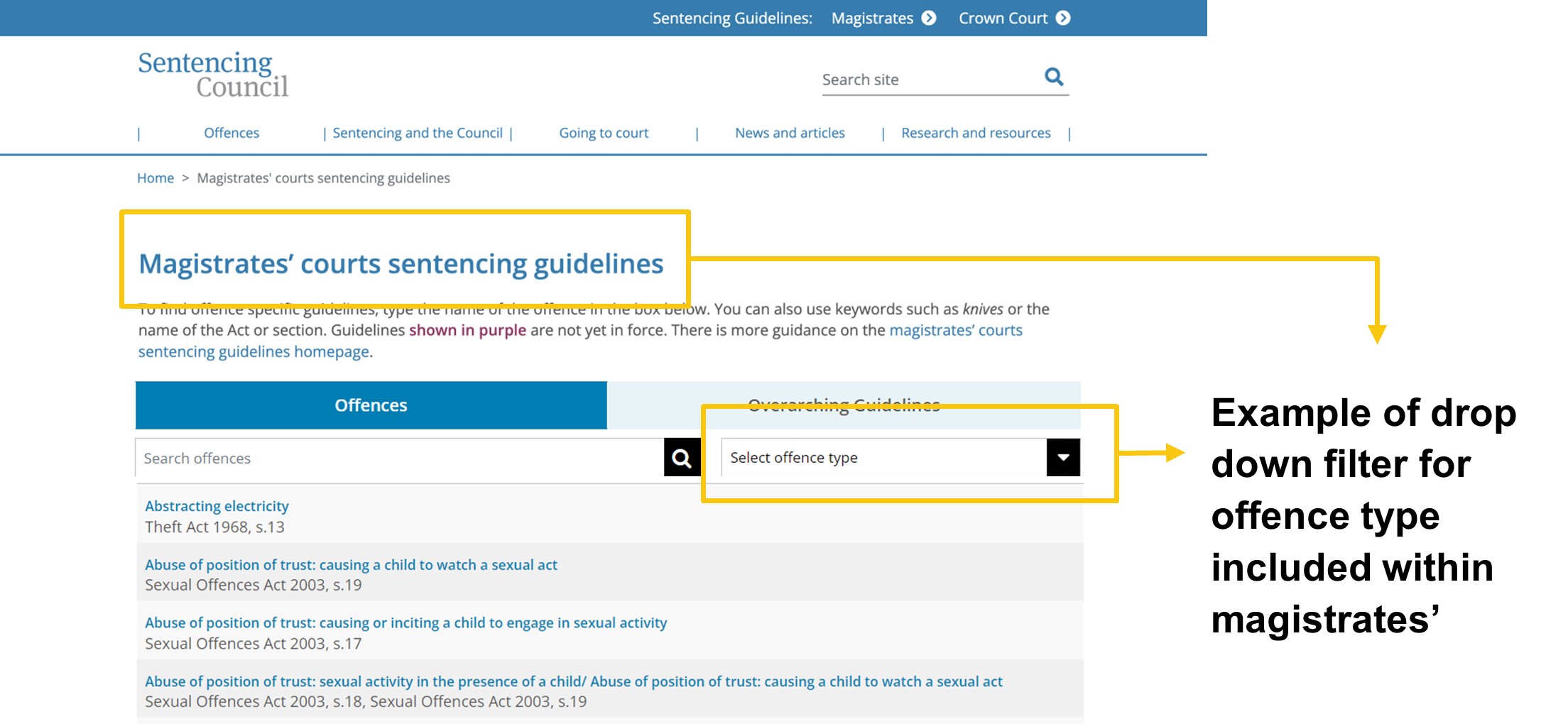

When magistrates were asked by researchers about whether a dropdown filter of offence types (as in the Crown Court guidelines) would be useful for the magistrates’ court guidelines, this was considered to be “very helpful” and they would “love that”.

Recommendation A4: provide a dropdown filter of offence types for the magistrates’ courts guidelines.

Priority: high

A dropdown filter of offence types (as in the Crown Court guidelines) should be provided for the magistrates’ court guidelines.

In addition to providing a dropdown filter, the Council could also consider splitting the Sexual Offences category into two categories, in order to reduce the number of guidelines in this single category. For example, ‘Sexual offences (excluding against children),’ and ‘Sexual offences against children.’ This would reduce the number of guidelines in each of these categories, making it easier to review the guidelines listed in these offence categories.

An example of how the recommendation for a filter could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Mocked up example of recommendation A4

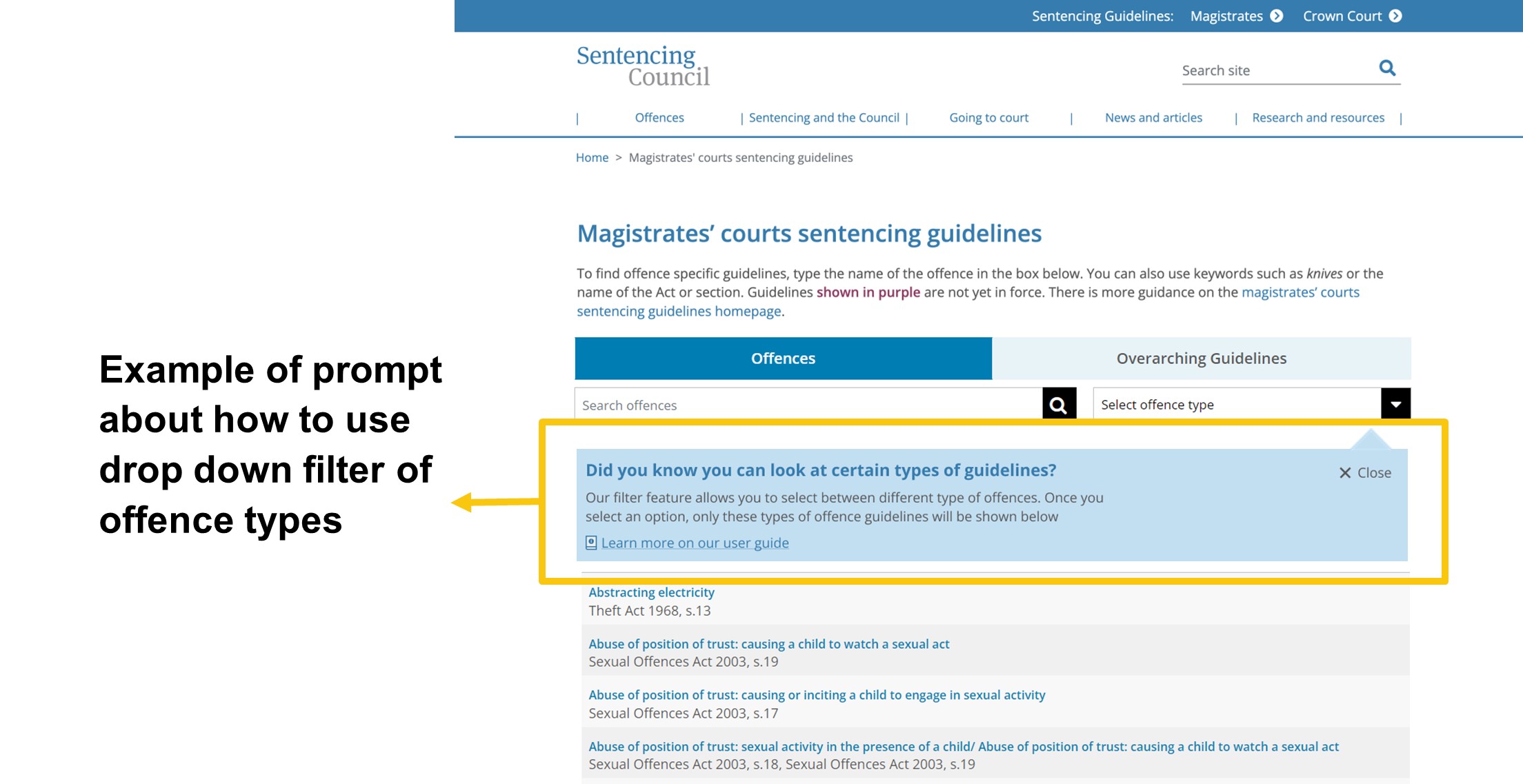

Finding A5: not all circuit judges were aware of the dropdown filter of offence types on the Crown Court guidelines

Some circuit judges were not aware of the dropdown filter of offence types on the Crown Court guidelines until researchers asked them about this. They did not notice this because they were used to entering terms into the search bar. One sentencer stated they “hadn’t used [the filter function] before…you get stuck in your own way of doing things”.

Recommendation A5: provide time-limited prompts about this feature on the Crown Court guidelines.

Priority: low

The Council could provide a small box with brief information about how to use this dropdown filter. This box should automatically open when the Crown Court guidelines are accessed. It should be clearly located close to the dropdown filter.

In order to promote awareness of the feature, while limiting the ‘visual noise’ on the Crown Court guidelines, this prompt should be provided for a limited time (e.g. one month). Additionally, this should be visible only the first time a person accesses the Crown Court guidelines. Given that judges have their own laptops, this provides a non-intrusive way to provide additional information.

This feature could also be used to notify sentencers of new functions and features on the guidelines (for example providing a drop down filter of offence types in the magistrates’ court guidelines, as noted in Recommendation A4: provide a dropdown filter of offence types for the magistrates’ courts guidelines).

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Mocked up example of recommendation A5

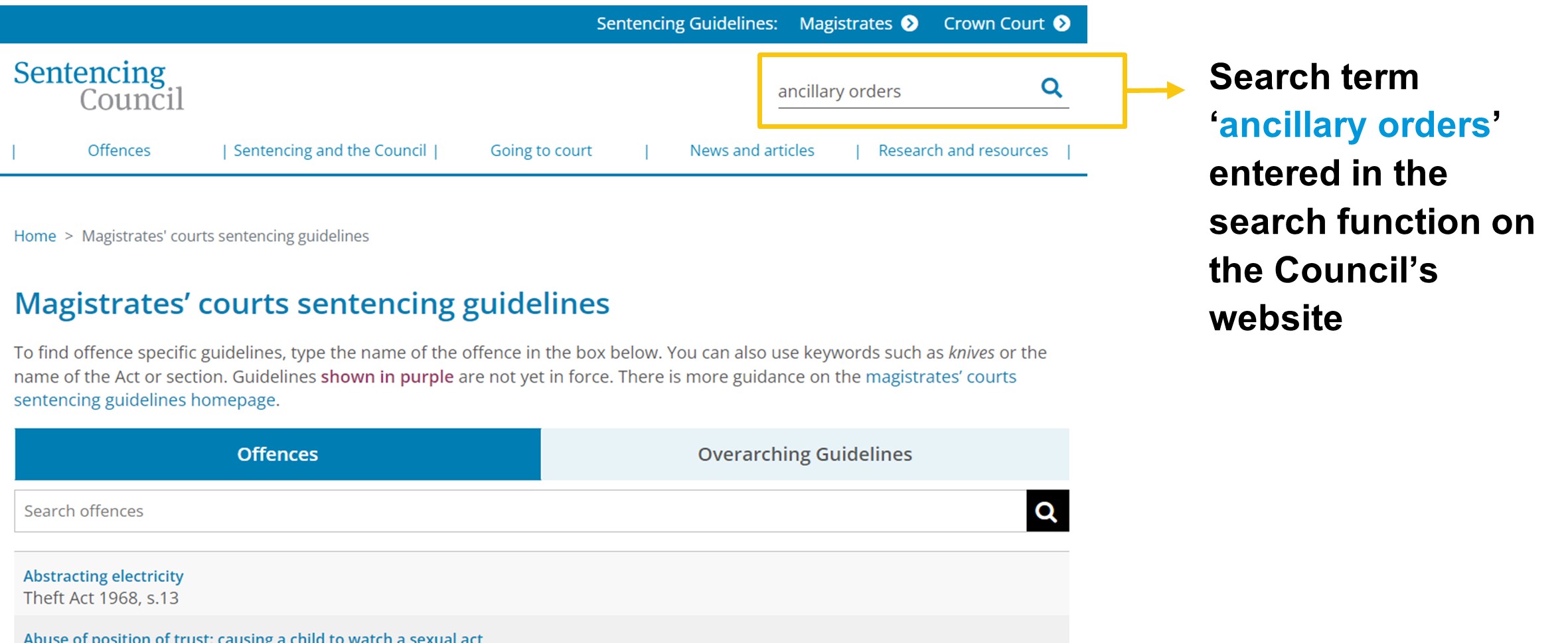

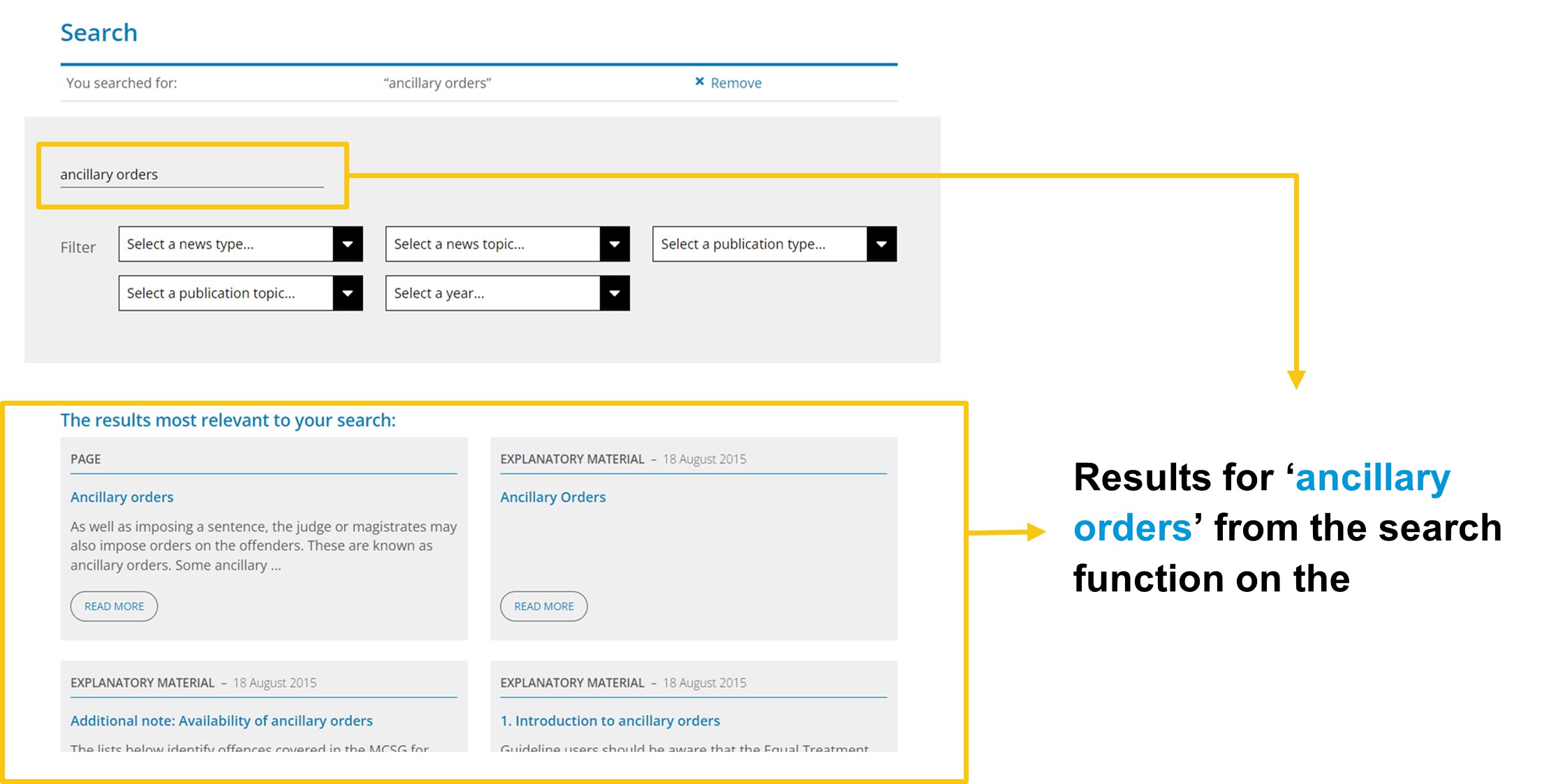

Finding A6: some sentencers try using the guideline search bar to find explanatory materials or other sentencing resources, but currently need to remember this is only available from a different search bar

Some sentencers attempted to use the search function on the offence specific guideline search pages to locate additional sentencing resources. Examples of these types of resources included explanatory materials such as ancillary orders (e.g., restraining order) and fines and financial orders (e.g., suggested starting amounts of compensation for victims who have sustained physical and mental injuries). One magistrate also noted they had tried to search for overarching guidelines using this search function.

While this information is available on the Council’s website, it is not searchable through the search bar on the offence specific guideline page. Some sentencers indicated it would be helpful to search for these types of additional information, rather than having to click through links elsewhere on the Council’s website (e.g. via the blue sidebar). It was also suggested to be beneficial for the search function to locate information within the text of sentencing-related documents hosted on the Council’s website (e.g. bail conditions listed in the Adult Court Bench Book).

Nonetheless, there were some sentencers who were aware they could use the separate ‘site search’ function on the Council’s website to find additional information (see Figures 17 and 18 for examples). However, they stated they did not use this search function often and primarily used the search bar on the offence specific guideline pages.

Figure 17: Example of entering ‘ancillary orders’ into the separate ‘search site’ function on the top-right of the Council’s webpages

Figure 18: Partial search results from keywords ‘ancillary orders’ using the ‘search site’ function on the Council’s website

Recommendation A6: increase the scope of the search function on the offence specific guideline search pages to include additional sentencing resources on the Council’s website.

Priority: medium

While the site search bar in the top right-hand corner of the Council’s website is able to locate additional sentencing information, sentencers were observed almost exclusively using the search bar in the offence specific guidelines page. Increasing the scope of the search bar for the offence specific guidelines would make it easier to find relevant sentencing information. Under the current design of the website, sentencers have to remember which search bars need to be used to find different types of information.

The search functionality for the offence specific guidelines should also be expanded to include additional information such as overarching principles, explanatory materials and the Bench Books.

The results should be presented in a similar manner to offence specific guidelines. However, results for additional types of information should be easily distinguished from these. This could be achieved through labelling the type of information within the search results (e.g. offence specific guidelines, explanatory materials, etc.)

This could also be incorporated with Recommendation A2 (refining the layout of search results), where sentencers are provided with a tool to filter search results. This filter should be set to show offence specific guidelines as the default setting. This would avoid providing too many different types of search results to sentencers using this search function.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 19 below.

Figure 19: Mocked up example of recommendation A6

Finding A7: the search function does not let sentencers know if they are searching for an offence which does not have a guideline, resulting in sentencers being unsure if they are using the search function correctly to locate offence specific guidelines

Sentencers both expressed, and were observed to have difficulties with, determining if they were searching for an offence specific guideline which did not exist. When searching for such an offence, typically no search results were presented. However, this did not give a clear indication that the offence specific guideline did not exist or was not in force, or whether the search function had failed to provide a result.

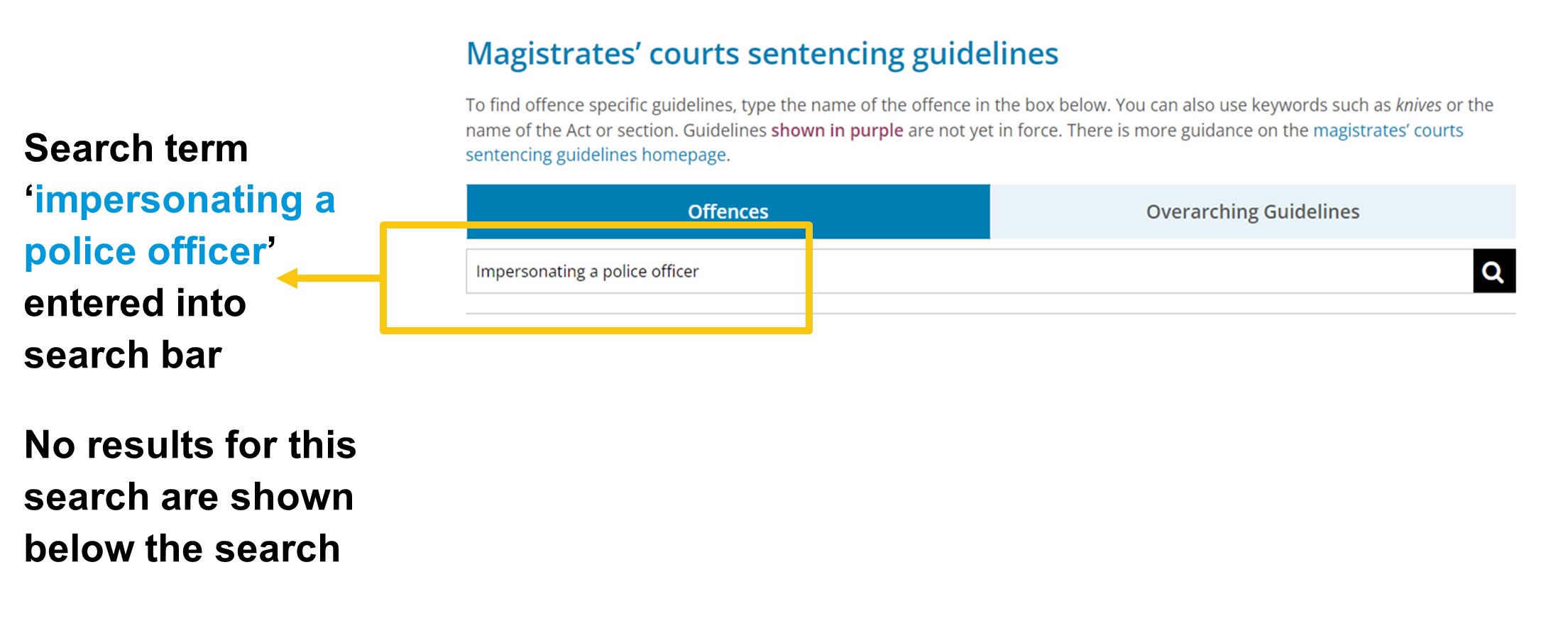

This issue was further compounded by difficulties using the search functionality. For example, one sentencer reported attempting to find a guideline for the offence of ‘Impersonating a Police Officer’ (Police Act 1996, s.90). Different search terms were used, though each had no results. The sentencer assumed they may not have been entering an appropriate search term. Only after multiple search attempts had they realised there may not be a guideline for this offence.

Figure 20: Example search for offence of ‘Impersonating a Police Officer’ on the magistrates’ court guidelines

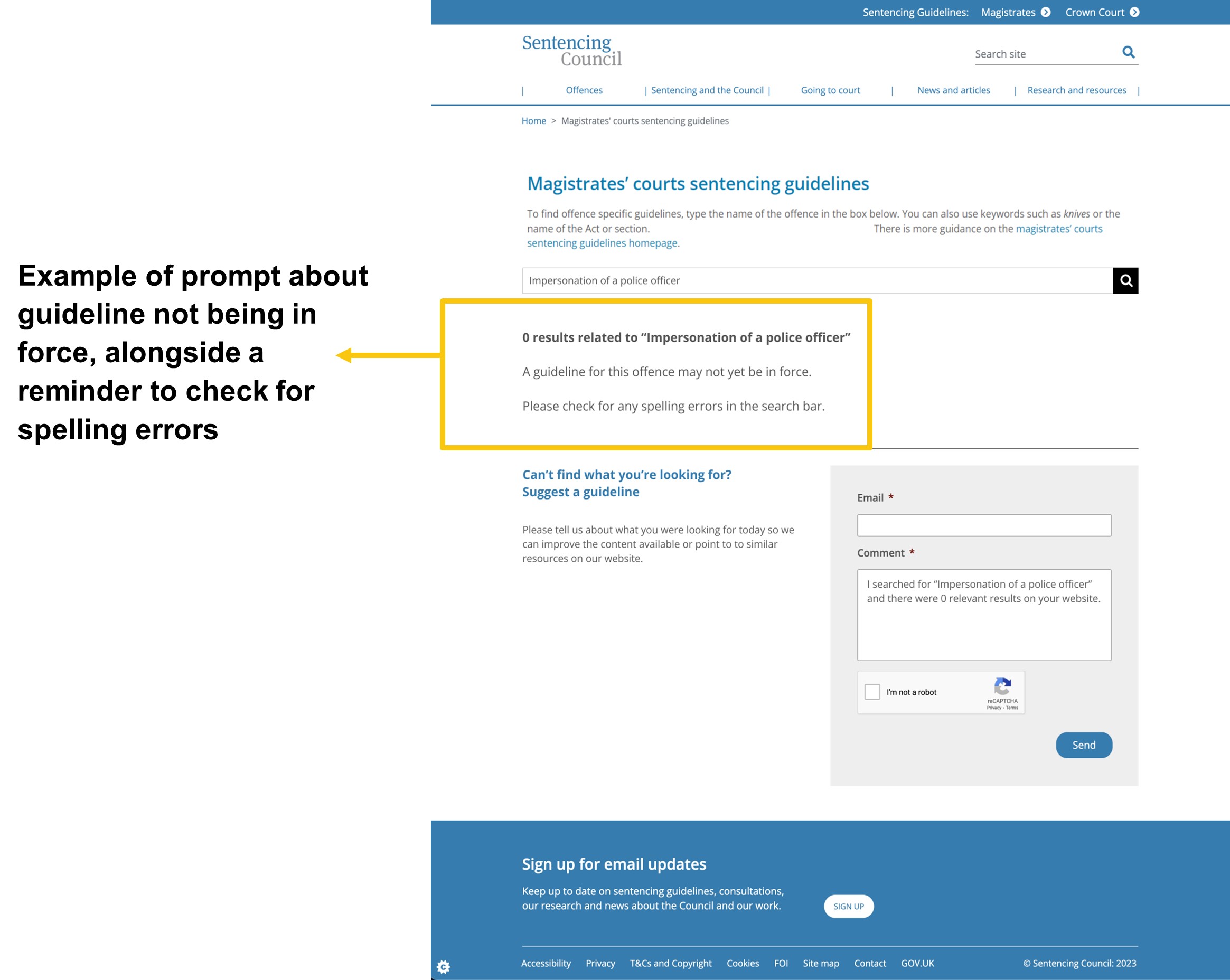

Recommendation A7: provide text prompts to sentencers when searching for guidelines which have not yet been developed.

Priority: medium

Provide prompts when sentencers might be searching for guidelines which do not yet exist. For example, a prompt could be shown when there are no guidelines identified in a search result, suggesting to sentencers that the offence being searched for may not currently have a guideline.

However, an error in search term may also provide no search results. To mitigate against suggesting to sentencers that guidelines may not exist in cases (where these offence specific guidelines are available but have not been listed in the search results), the prompt should also indicate there may be a spelling error in the search term.

This prompt could also indicate that sentencers could refer to the General guideline: overarching principles, where there are no offence specific guidelines are available. For example, this prompt could include the phrase “If there is no offence specific guideline for the offence you are searching for, please use the General guideline.”

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 21.

Figure 21: Mocked up example of recommendation A7

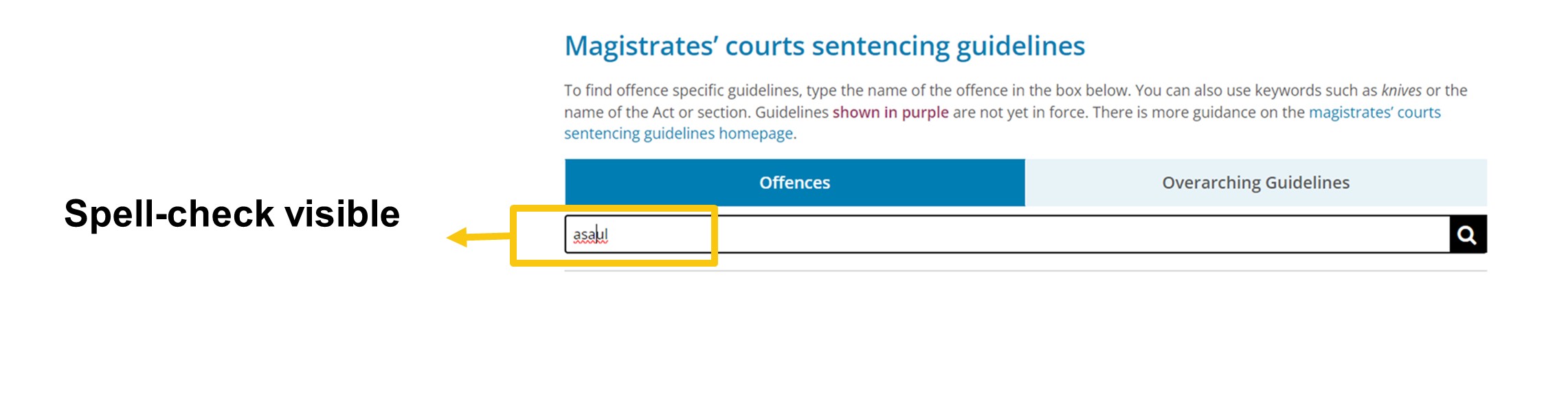

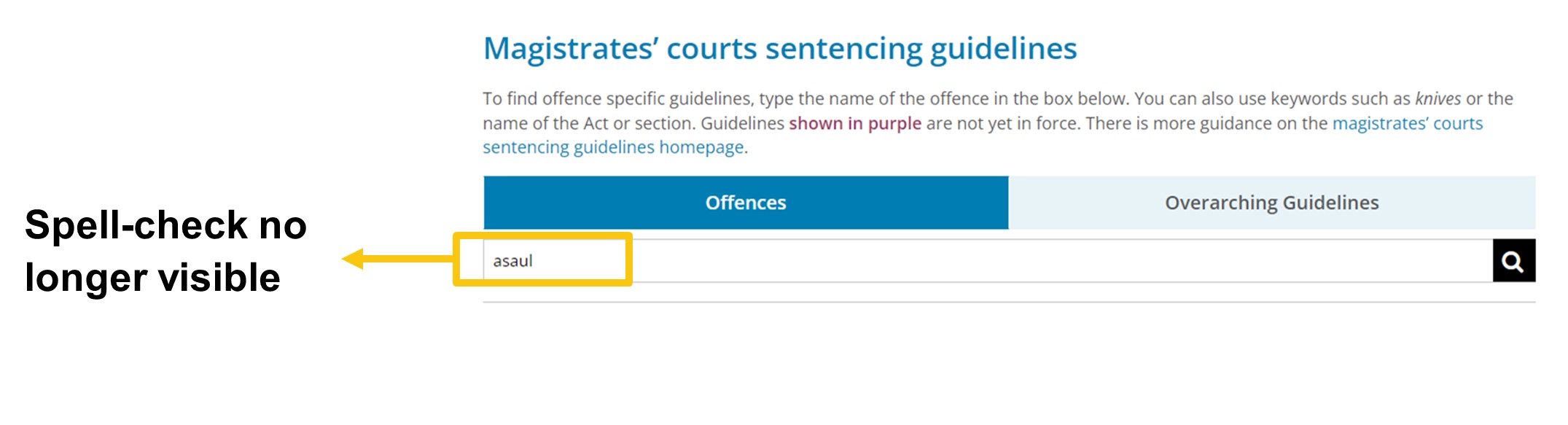

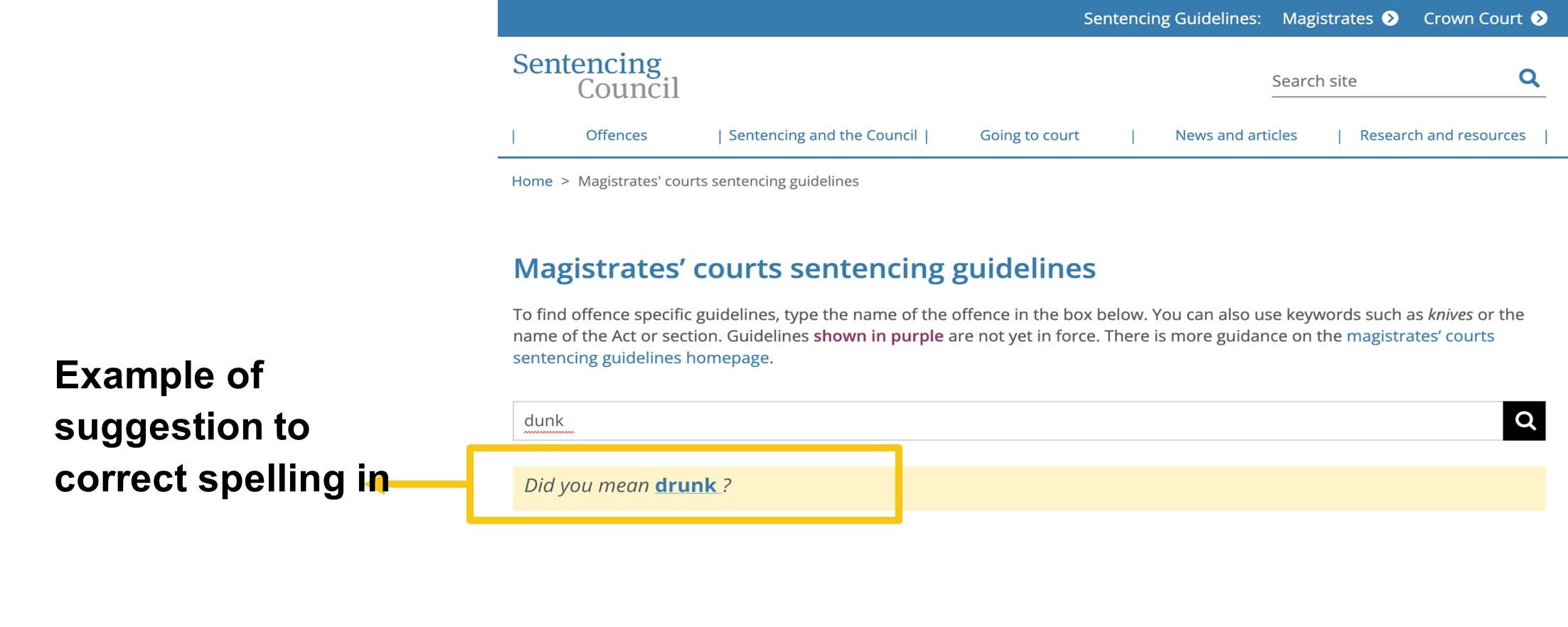

Finding A8: the spell-check function in the search bar for offence specific guidelines does not consistently indicate spelling errors

Sentencers noted certain offence names could be difficult to type into the search bar, especially if they were under time pressure. Most were aware there was a spell-check function (i.e. a red underline beneath spelling errors). An example of this spell-check function in the search bar on the offence guidelines search page, is shown in Figure 22, below. However this remained visible only if sentencers did not click outside of the search bar (including clicking on the search icon).

Figure 22: Spell-check visible in search bar, whilst cursor has clicked on search bar

Figure 23: Spell-check no longer visible, after clicking out of the search bar

Recommendation A8: refine the spell-check function to be consistently visible to sentencers and provide suggestions for correct spelling.

Priority: medium

The search function should be refined to indicate spelling errors, even after sentencers have clicked outside of the search bar. Additionally suggested search terms with accurate spelling should be provided.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 24.

Figure 24: Mocked up example of recommendation A8

B. How easy is it for sentencers to use the guidelines given the current layout and format of the guidelines?

Finding B1: sentencers generally felt the guidelines were well laid out, though could be improved to reduce scrolling back and forth between different sections

Sentencers felt the offence specific guidelines followed a logical order and valued having all of the relevant steps included within them. Currently, these types of guidelines include a step-by-step process that sentencers should take when making sentencing decisions. There are typically nine steps including:

- determining the offence category

- starting point and category range

- consider any factors which indicate a reduction for assistance to the prosecution

- reduction in sentence for a guilty plea

- dangerousness

- totality principle

- compensation and ancillary orders

- reasons for the sentence

- consideration for time spent on bail (tagged curfew)

Additionally, these steps are provided in a consistent manner for most offence specific guidelines, which facilitates sentencers’ decision making when dealing with different offences.

While information included within offence specific guidelines was perceived to be helpful, some magistrates reported they were faced with too much information, with one magistrate stating these were “too busy” and had “too many words”. They also felt some of the information was not as relevant to them as it was to judges (for example, when the starting points and category ranges for a sentence was beyond the power of magistrates to impose). Some reported feeling overwhelmed by the amount of information, especially when making sentencing decisions sitting in court. This was particularly the case when looking at the overarching guidelines for ‘Sentencing offenders with mental disorders, developmental disorders, or neurological impairments’, ‘Totality’ and ‘Sentencing Children and Young People’.

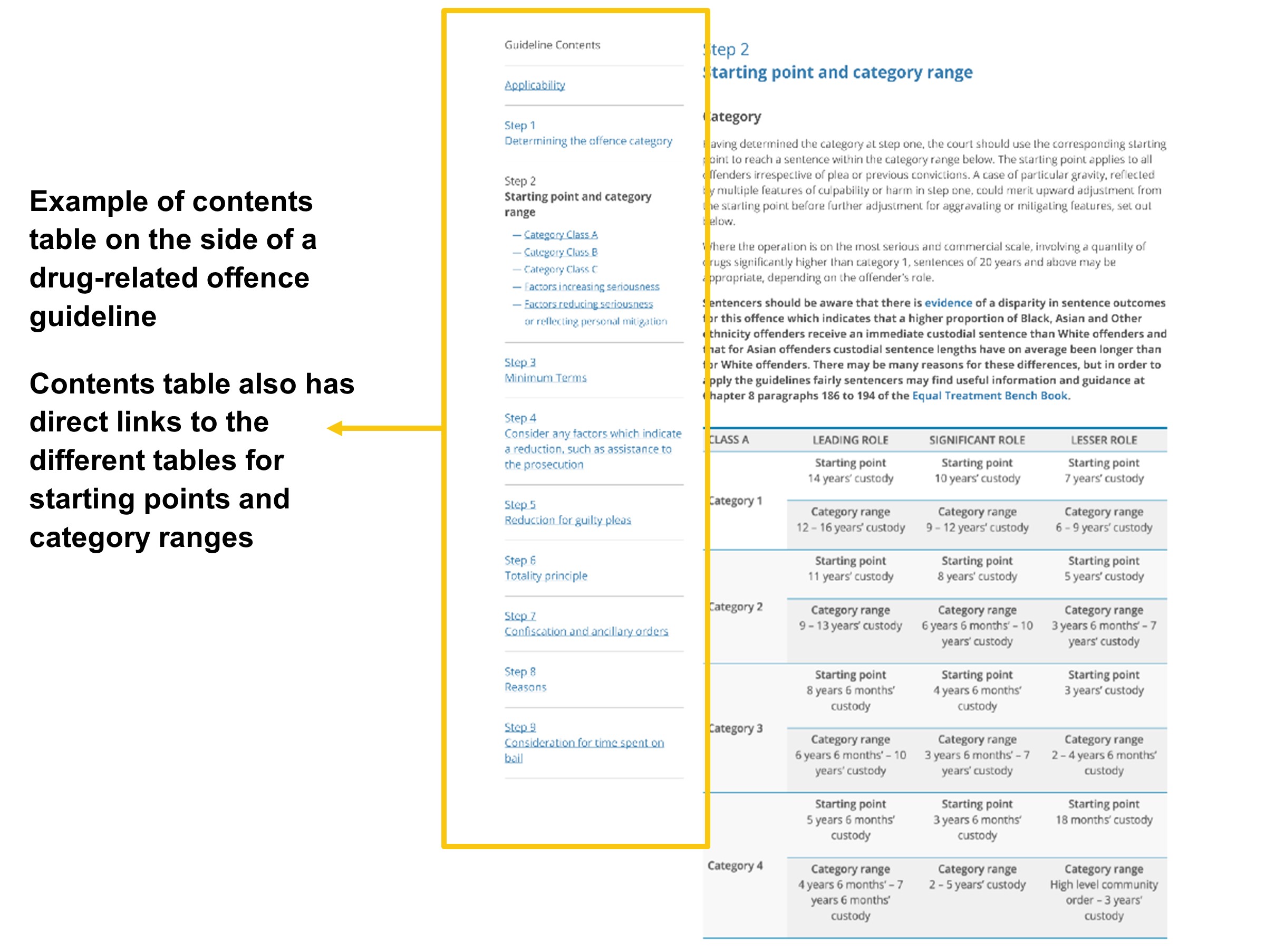

Further, the volume of information available led to magistrates spending additional time scrolling through the guidelines to locate relevant sections for their cases. This process was time consuming, especially when magistrates were dealing with multiple cases a day.

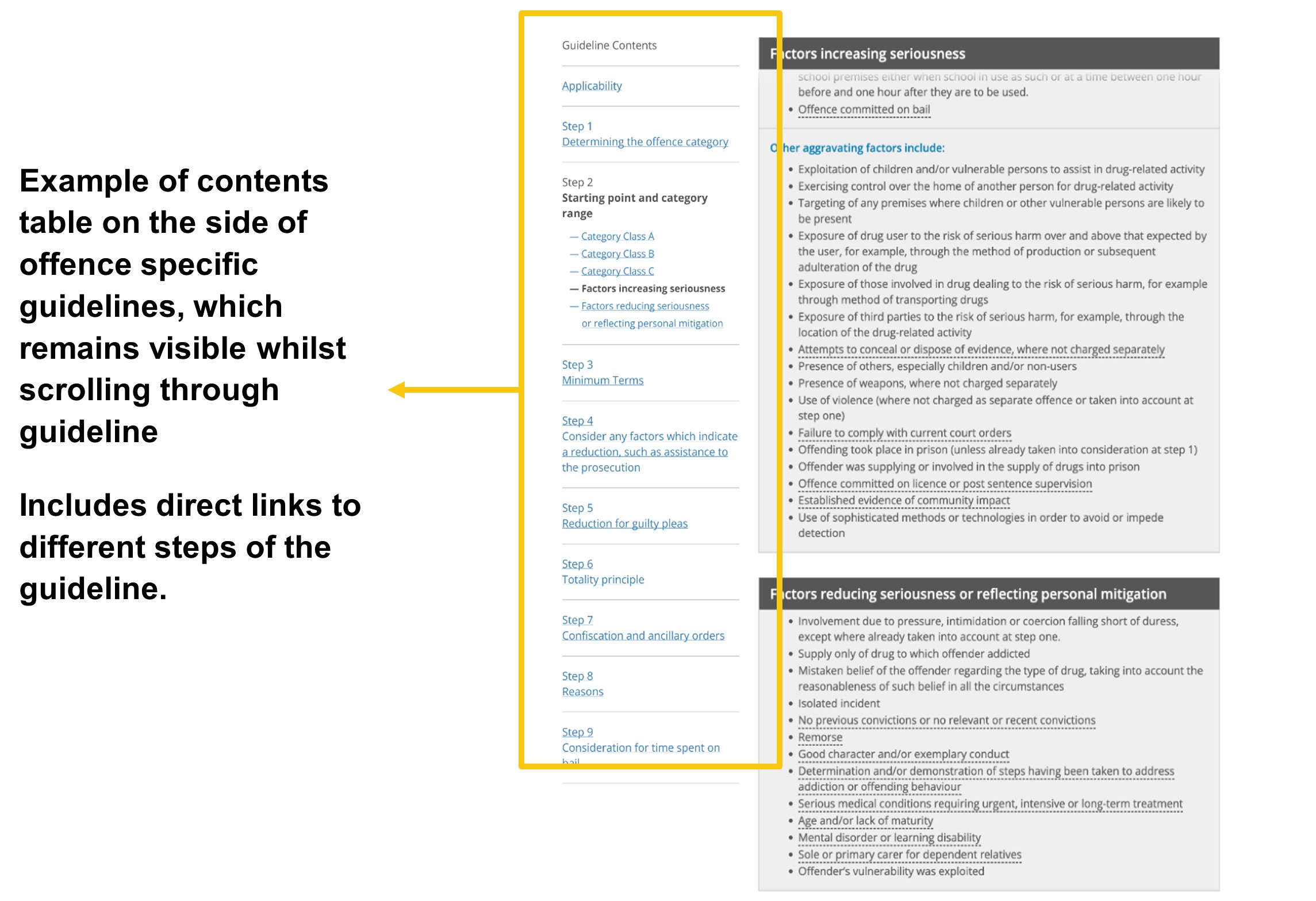

Recommendation B1: provide a floating contents table linking to different sections of the guidelines and increase the spacing between different steps of offence specific guidelines.

Priority: high

Guidelines should have a short contents table on the side of the guidelines (similar to the contents tables in overarching guidelines). This table should be presented on either the left or right side of the guidelines, though having this on the left side may make it slightly quicker for sentencers to navigate the guidelines (Kingsburg and Andre, 2004).

As with the overarching guidelines, the table should be hyperlinked to different steps within the guidelines. Additionally, the different steps of the guidelines should also be spaced further apart, to help reduce the perception of having to navigate through a lot of information.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 25.

Figure 25: Mocked up example of recommendation B1

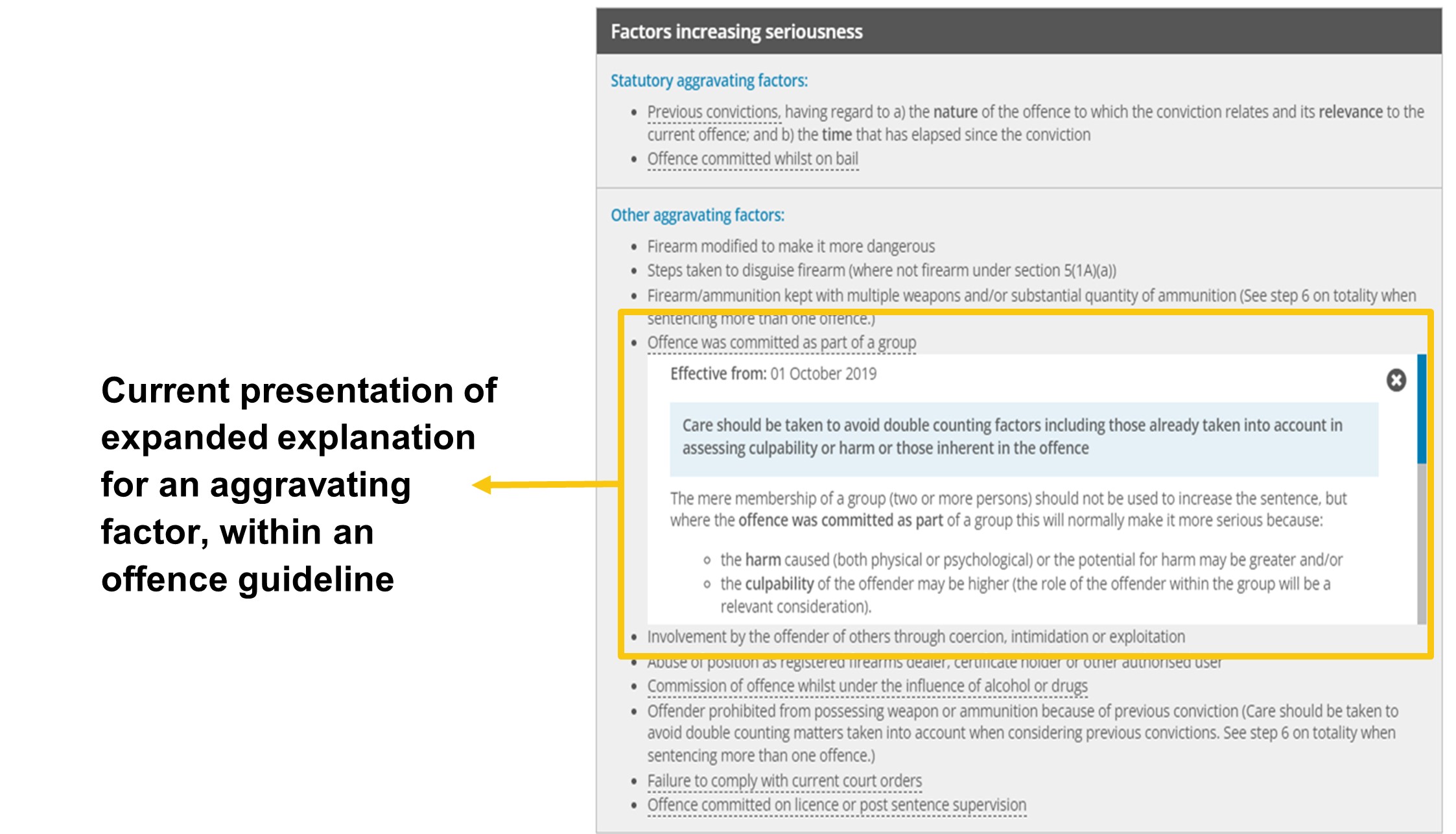

Finding B2: Sentencers were not always aware that some aggravating and mitigating factors included expandable boxes with additional information

Some sentencers were observed clicking on aggravating factors and mitigating factors to reveal additional information within an expandable dropdown box (known as the ‘expanded explanations’ for guidelines). They liked having the option to access this additional information (rather than this being constantly visible) and adding to the amount of information within the offence specific guidelines.

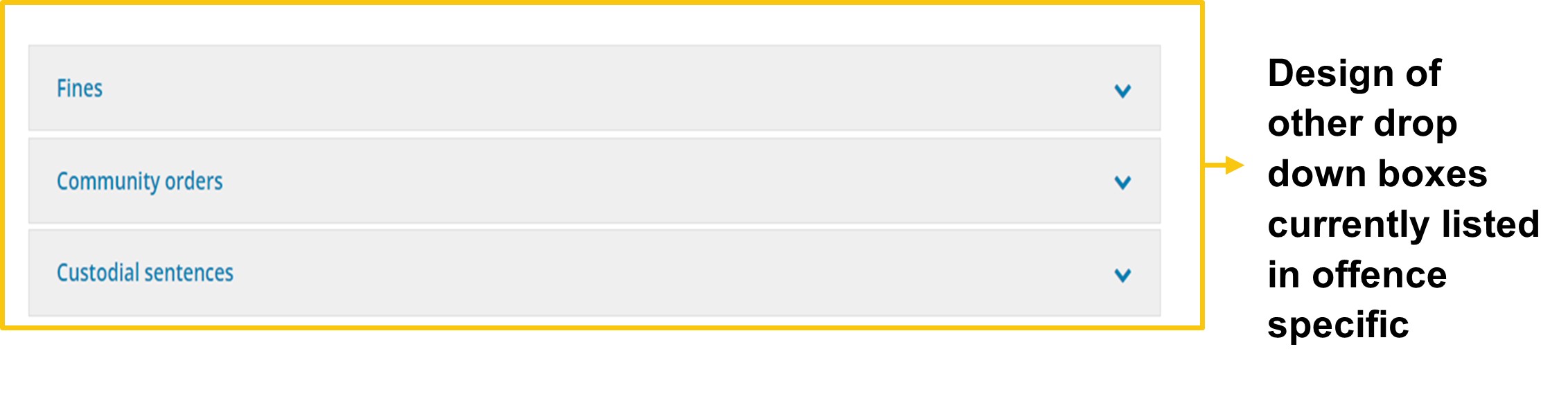

However, not all sentencers were aware that certain aggravating or mitigating factors had expanded explanations. They remarked they had not considered the dotted line beneath these factors to be indicative of having an expandable box. This was not consistent with how other dropdown boxes were presented in the guidelines (often with a small downwards arrow on the right side of the title). Moreover, some participants also lacked awareness about the existence of other dropdown boxes within offence specific guidelines.

Figure 26: Expanded explanations for the aggravating factor ‘Offence was committed as part of a group’ for the offence of possession of a prohibited weapon

Separately, depending on sentencers’ familiarity with these factors, certain offences, and extent of their legal knowledge, they felt it was not necessary to access this information. Judges felt these boxes might be more useful for magistrates or less experienced sentencers. Some magistrates noted seeking advice from legal advisers rather than accessing the information within these expandable boxes themselves.

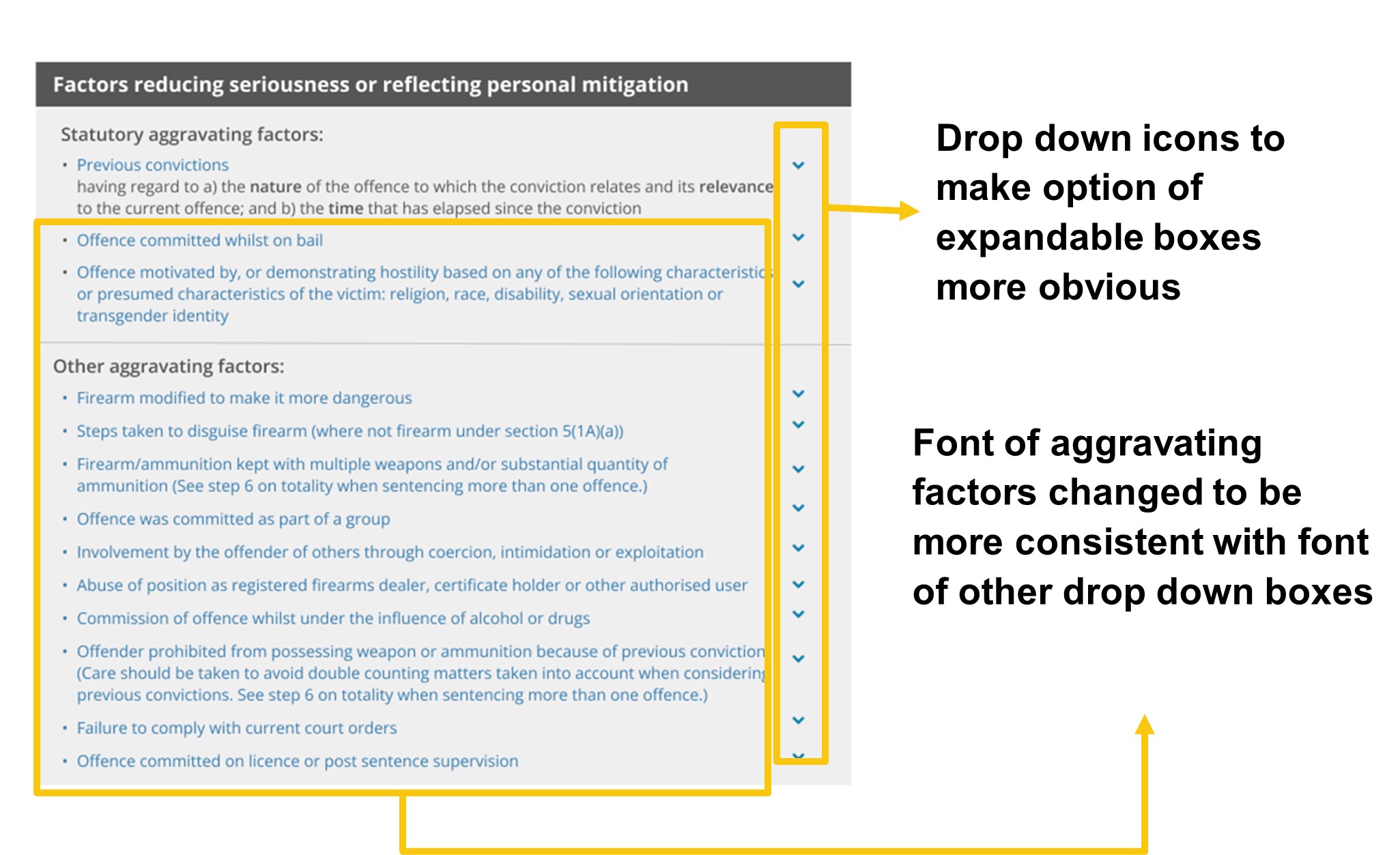

Recommendation B2: refine the design of aggravating and mitigating factors within offence specific guidelines to be more consistent with how other dropdown functions are generally presented online.

Priority: medium

A dropdown icon next to the aggravating and mitigating factors that contain expanded explanations should be provided. This icon should change once it is clicked and the expanded explanation is presented. These expandable dropdown factors should be expanded fully when they are clicked. This would match the way other dropdown boxes within the guidelines operate.

Additionally, the font colour of factors with expanded explanations should also be different to those factors which do not have expanded explanations. The dotted line underneath the factors with expanded explanations should also be removed.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 27.

Figure 27: Mocked up example of recommendation B2

Figure 28: Comparison image of other dropdown boxes currently listed within offence specific guidelines

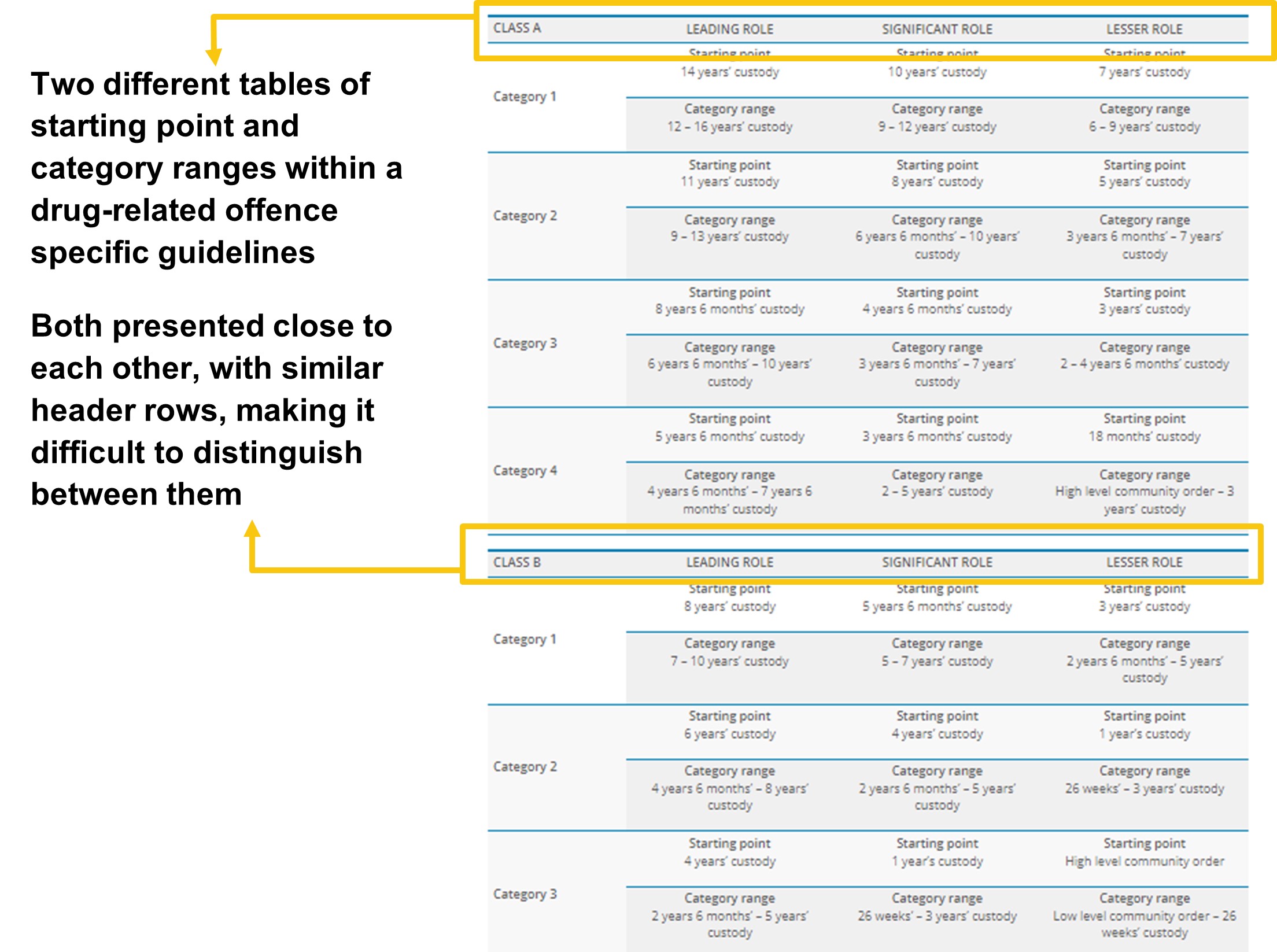

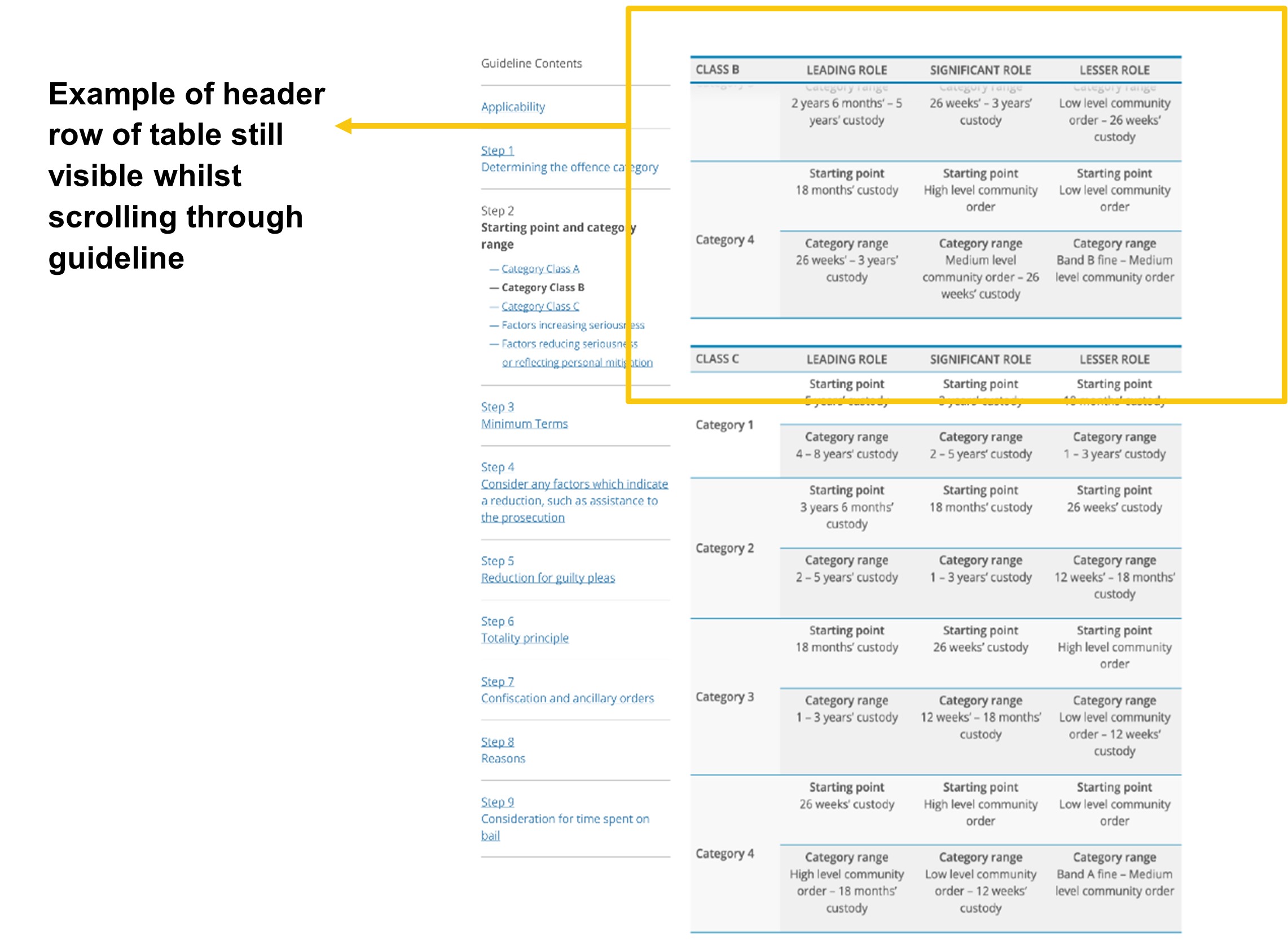

Finding B3: some offence specific guidelines contain multiple starting point and category range tables, which were sometimes confusing for sentencers

Within certain offence specific guidelines there are multiple tables for the starting point and category ranges (e.g. for drug-related offence specific guidelines, there are multiple tables for different classes of drugs). Sentencers did not always know if they were looking at the correct table. This was due to all tables looking the same, and header rows not being visible when scrolling through these tables. Some magistrates were observed using the incorrect table when making mock sentencing decisions.

Additionally, for drug-related offences sentencers suggested the guidelines should provide information on which substances belong to different classes of drugs.

Figure 29: Partial tables of starting point and category ranges for the ‘Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another’ guideline

Recommendation B3: make it easier for users to distinguish between the different tables of starting points and category ranges within offence specific guidelines.

Priority: medium

Provide a brief contents table in these offence specific guidelines (as also noted in Recommendation B1) that links to the different tables. Additionally, the heading of each table should be visible to users while they scroll through the table.

Examples of how this recommendation could be implemented are illustrated in Figure 30 and Figure 31.

Figure 30: Mocked up example of recommendation B3 (illustrating a contents table for the ‘Possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another’ guideline)

Figure 31: Mocked up example of recommendation B3 (illustrating the header row for starting point and category range table being visible whilst users scroll through the guideline)

C. How easy is it for sentencers to access different guidelines and additional sentencing resources on the Council’s website?

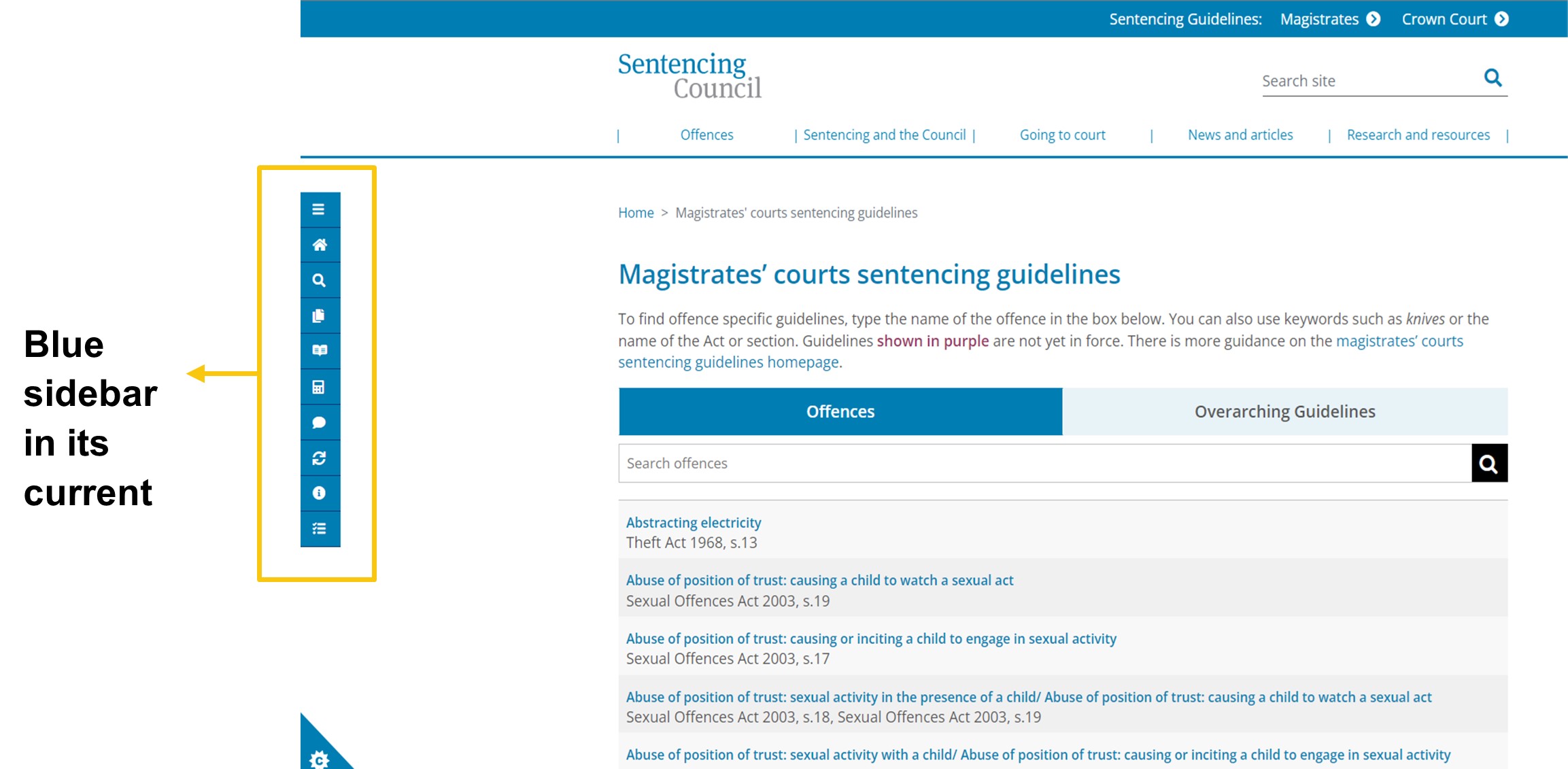

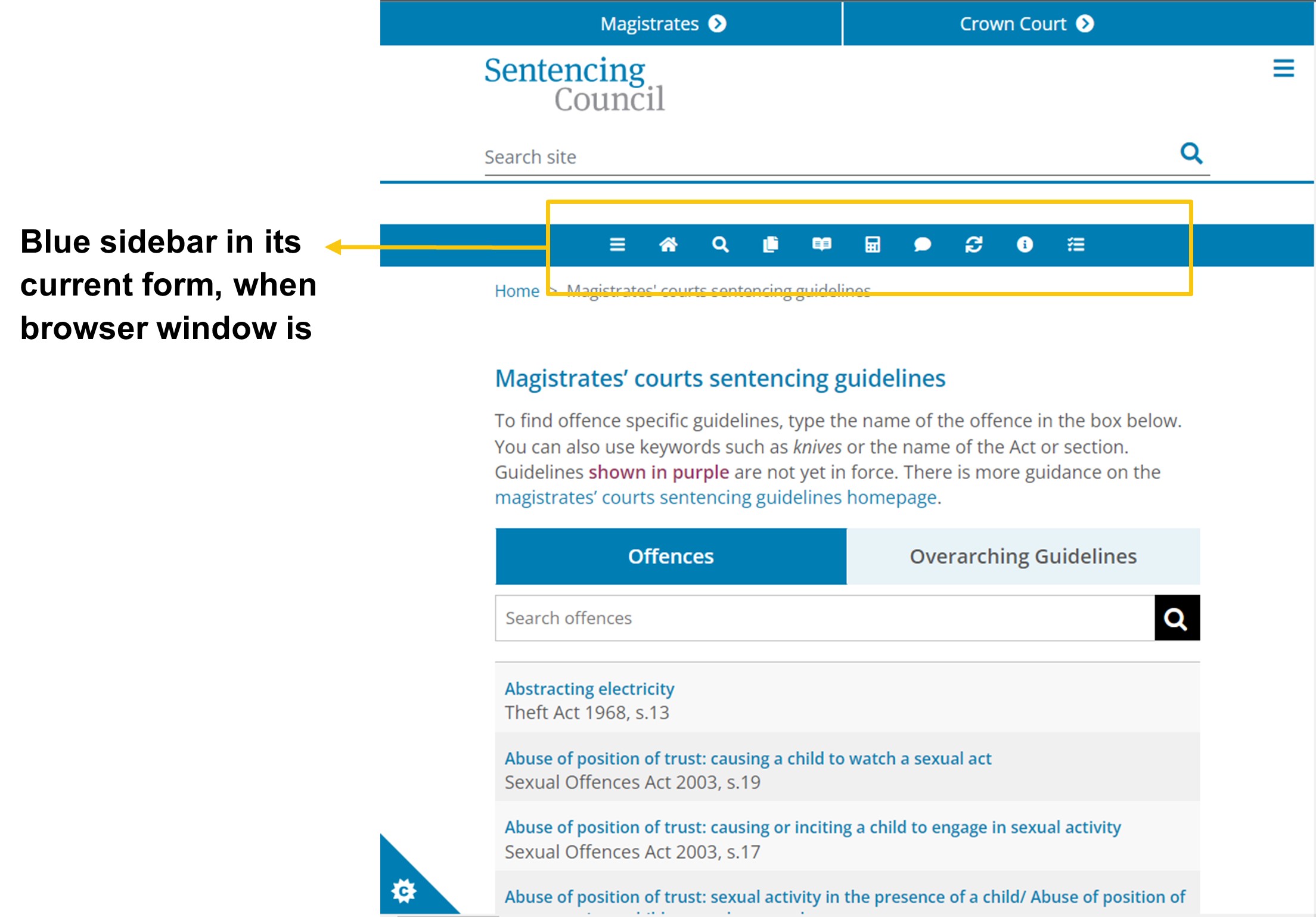

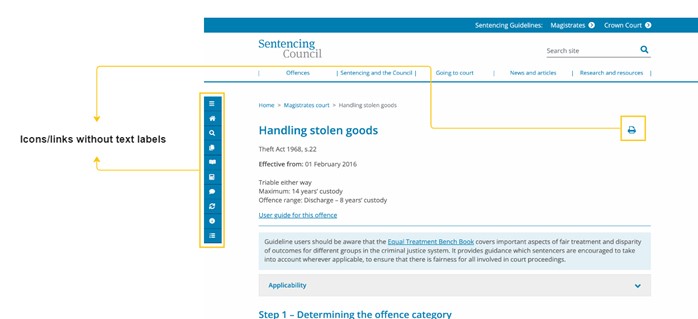

Finding C1: the blue sidebar was a useful shortcut to get to other sentencing resources, though it was not always clear exactly what resources were available through the sidebar

For guidelines in both the magistrates’ court and Crown Court, there is a blue sidebar on the left side of the page (as seen in Figure 32 below). This expandable blue sidebar contains links to other resources available on the Council’s website. Sentencers felt the blue sidebar on the left of the screen provided a quick shortcut to access frequently used resources. The sidebar was largely used as a mechanism to navigate to three main functions: the offence guideline search page, the fine calculator (a tool available on the Council’s website which can be used to calculate the total financial penalty in a case), and the overarching guidelines. However beyond these functions, sentencers both expressed and were observed having limited use for the sidebar.

In addition, some judges and magistrates were not aware of the blue sidebar, reporting that they hadn’t previously noticed it on the page and didn’t understand its purpose. Similarly, others stated they didn’t use many of the resources in the sidebar, as they were not aware of what resources the sidebar included.

Aside from the fine calculator and search icon, sentencers felt it was unclear what the other icons were for, often having to hold their cursor over an icon to understand what resources these icons referred to.

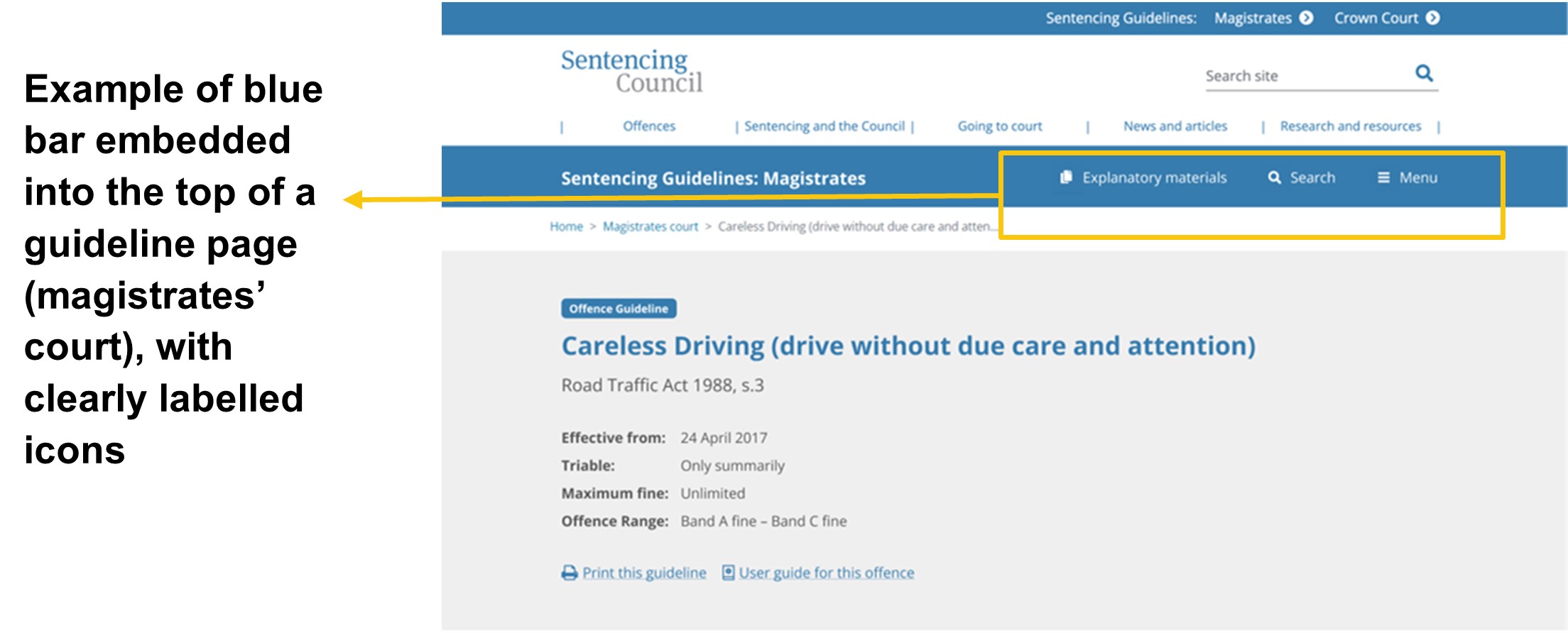

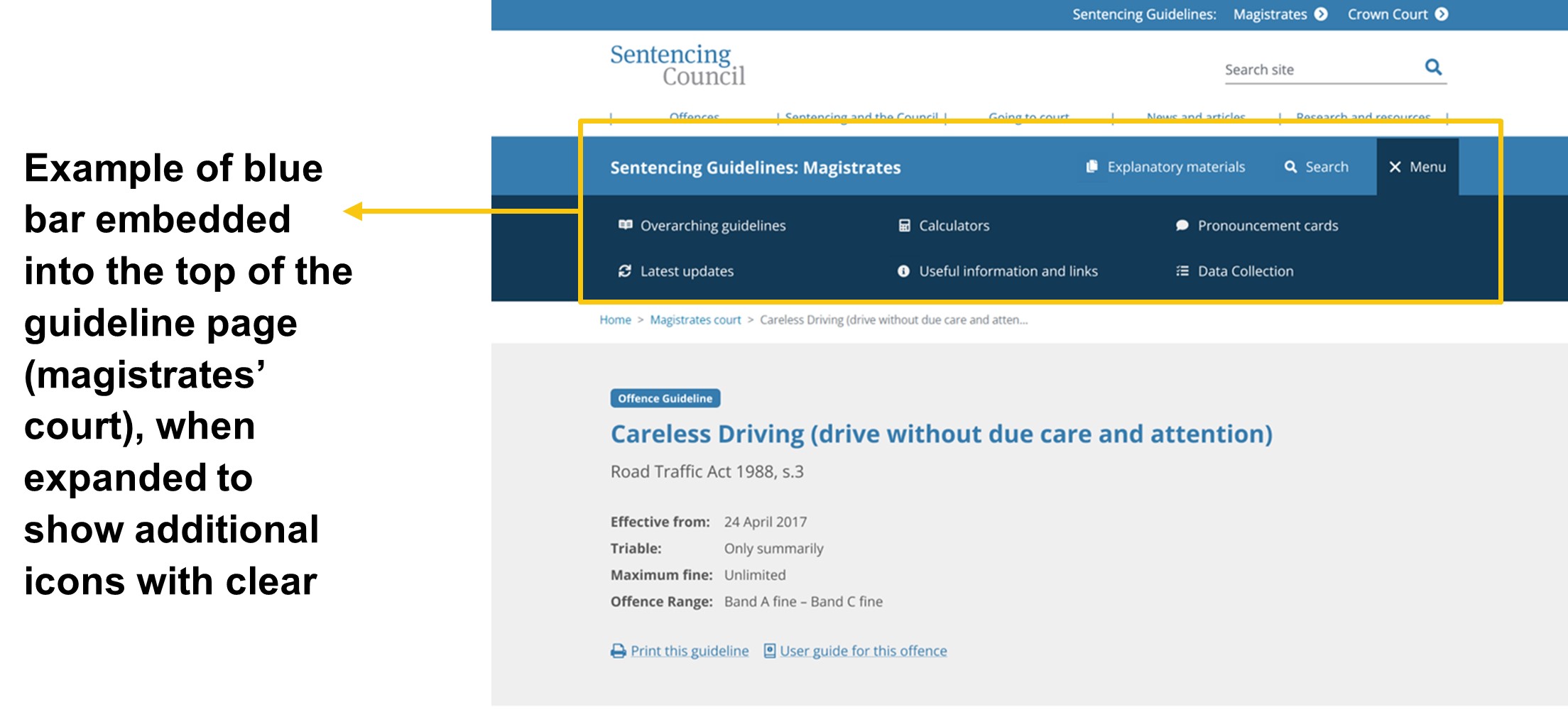

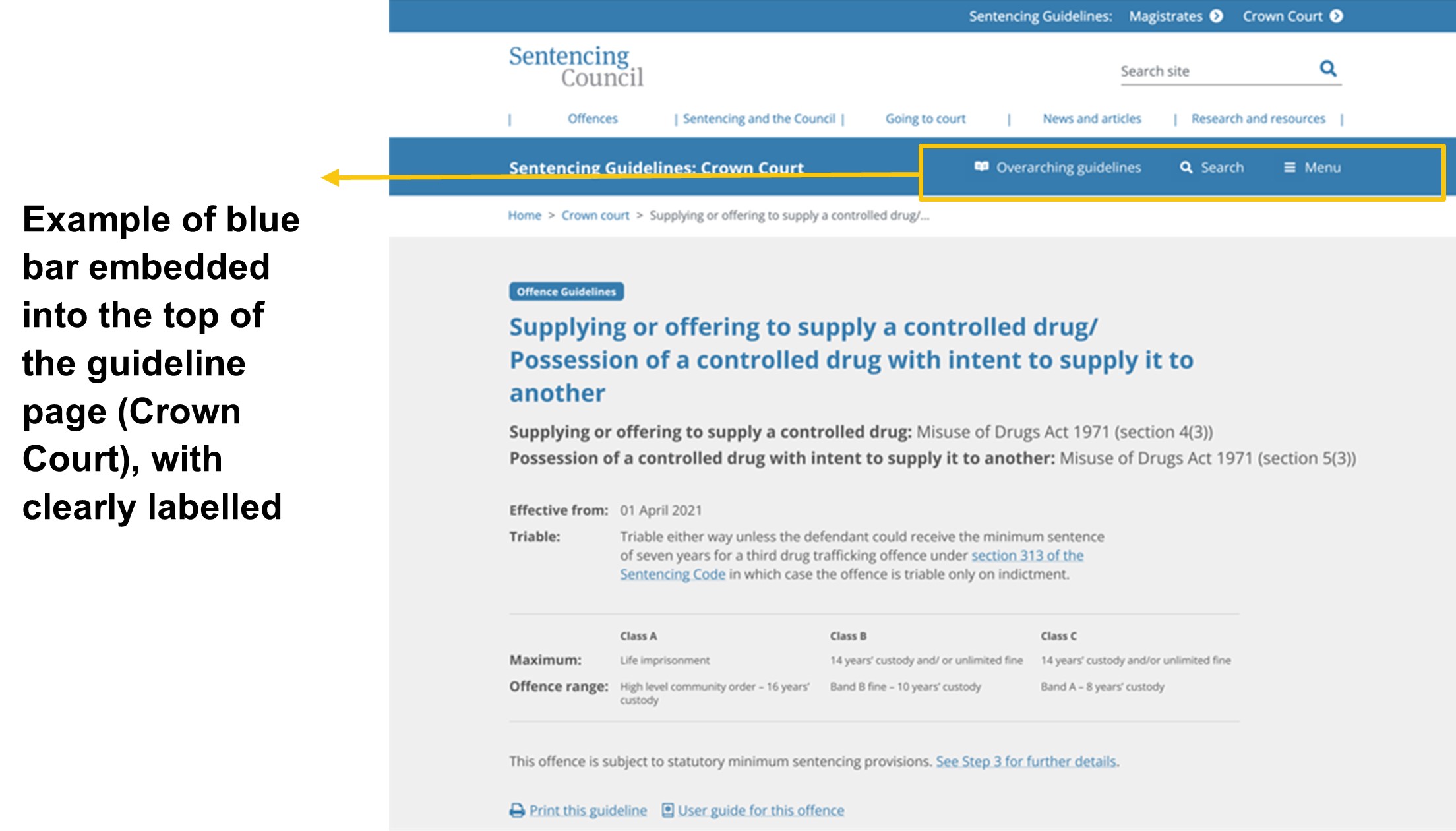

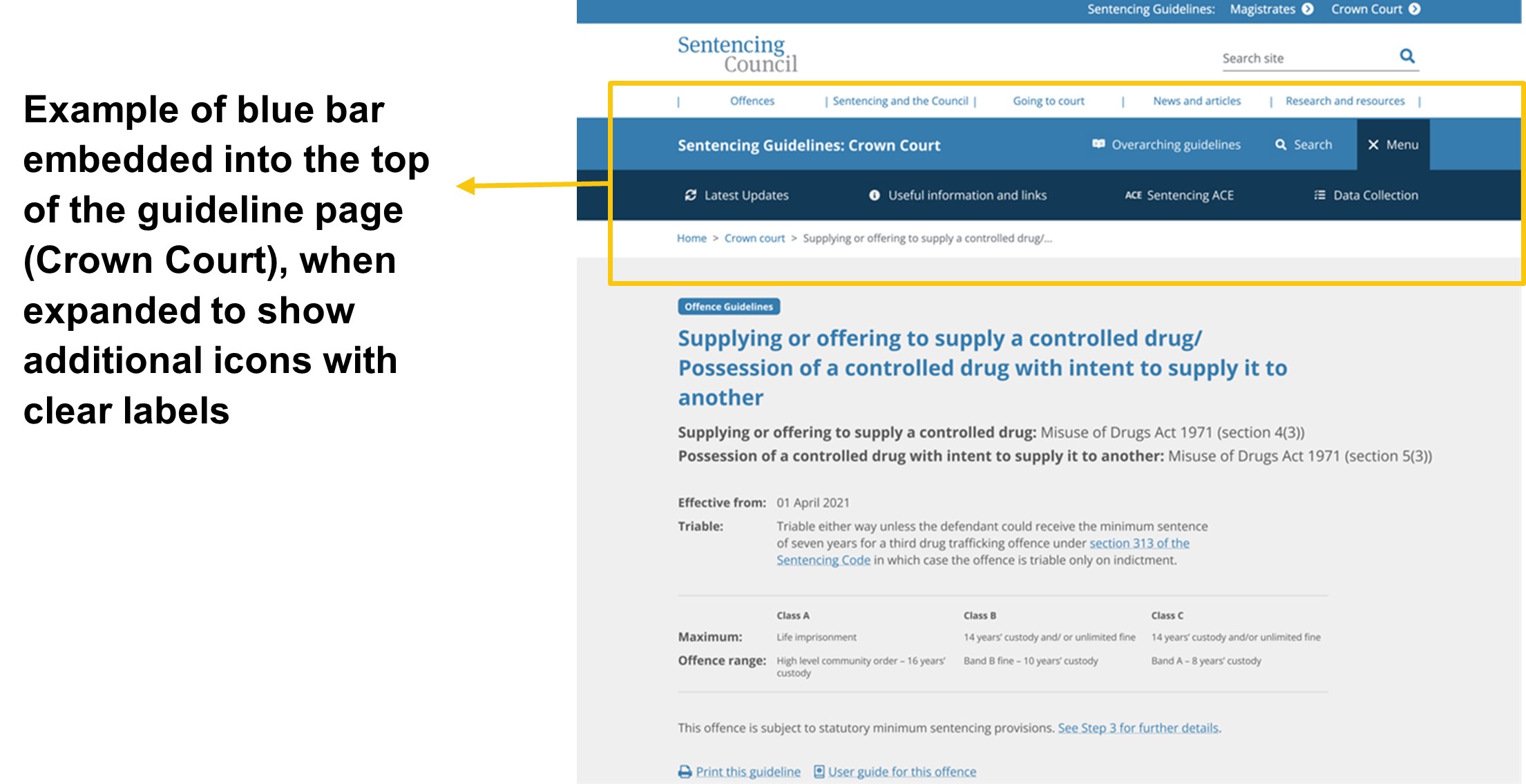

Recommendation C1: embed the blue sidebar at the top of the guideline pages and clearly label the icons.

Priority: medium

The blue sidebar should be embedded into the top of the webpage of the guidelines to make sentencers more aware of it. This should also remain visible when scrolling through the page. This will prevent users from having to scroll up each time they would like to use the blue bar.

It should be located at the top of the page and should remain here, as the location of the sidebar currently changes from the side of the guidelines to the top of the guidelines when the size of the browser is reduced (see Figures 32 and 33). This will help give sentencers a sense of consistency.

Additionally, the names of icons should be presented next to the icons, to help make it clear what these refer to.

Figure 32: Comparison image of blue sidebar as currently presented in the magistrates’ court guidelines

Figure 33: Image of blue sidebar for the sentencing guidelines when browser window is shortened to split-screen display

Examples of how this recommendation could be implemented are illustrated in Figures 34, 35, 36 and 37.

Figure 34: Mocked up example of recommendation C1 (for the magistrates’ court guidelines) showing embedded blue bar

Figure 35: Mocked up example of recommendation C1 (for the magistrates’ court guidelines) showing embedded blue bar when expanded

Figure 36: Mocked up example of recommendation C1 (for the Crown Court guidelines) showing embedded blue bar

Figure 37: Mocked up example of recommendation C1 (for the Crown Court guidelines) showing embedded blue bar when expanded

Finding C2: not all sentencers are aware of the information available in the explanatory materials

There is a lack of awareness among sentencers around the purpose of explanatory materials. When asked about these materials some sentencers seemed unsure of what constituted explanatory materials, and stated they did not refer to these on a regular basis. It is possible sentencers consider explanatory materials contain non-critical information, thereby discouraging them from referring to these on a regular basis. Moreover, some magistrates refer to their legal adviser rather than finding and reading additional information such as in explanatory materials.

Additionally, sentencers were not very familiar with how and where to find explanatory materials. Researchers observed sentencers undertaking a relatively complex process to locate relevant types of explanatory material they wanted. For example, sentencers spent a lot of time searching for certain explanatory materials (e.g. on restraining orders), but often landed on the wrong page and had to resume their search process.

However, other sentencers stated they were aware of the explanatory materials and found them useful when making sentencing decisions (e.g. when needing to refer to ancillary orders such as deprivation or restraining orders).

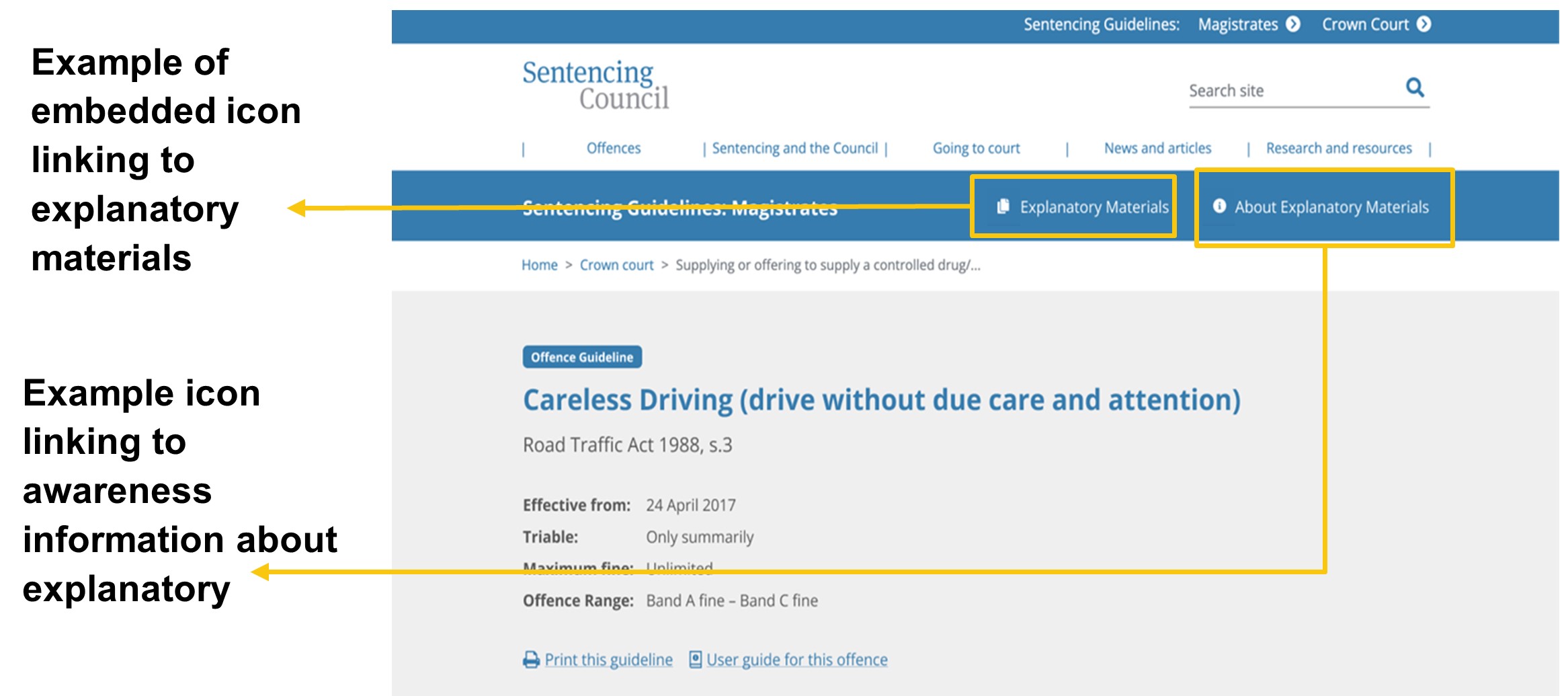

Recommendation C2: make the explanatory materials icon in the blue sidebar more obvious and provide awareness on the information it contains.

Priority: medium

Similar to Recommendation C1 (embedding the blue sidebar at the top of the guideline page), a clearly labelled icon with a link to the explanatory materials should be embedded at the top of the guideline pages. This icon should always be visible and clearly labelled.

The Council should also have an ‘additional information’ icon with a link to a page containing information about the explanatory material. This should include a brief explainer video with accompanying text about the explanatory materials.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 38.

Figure 38: Mocked up example of recommendation C2

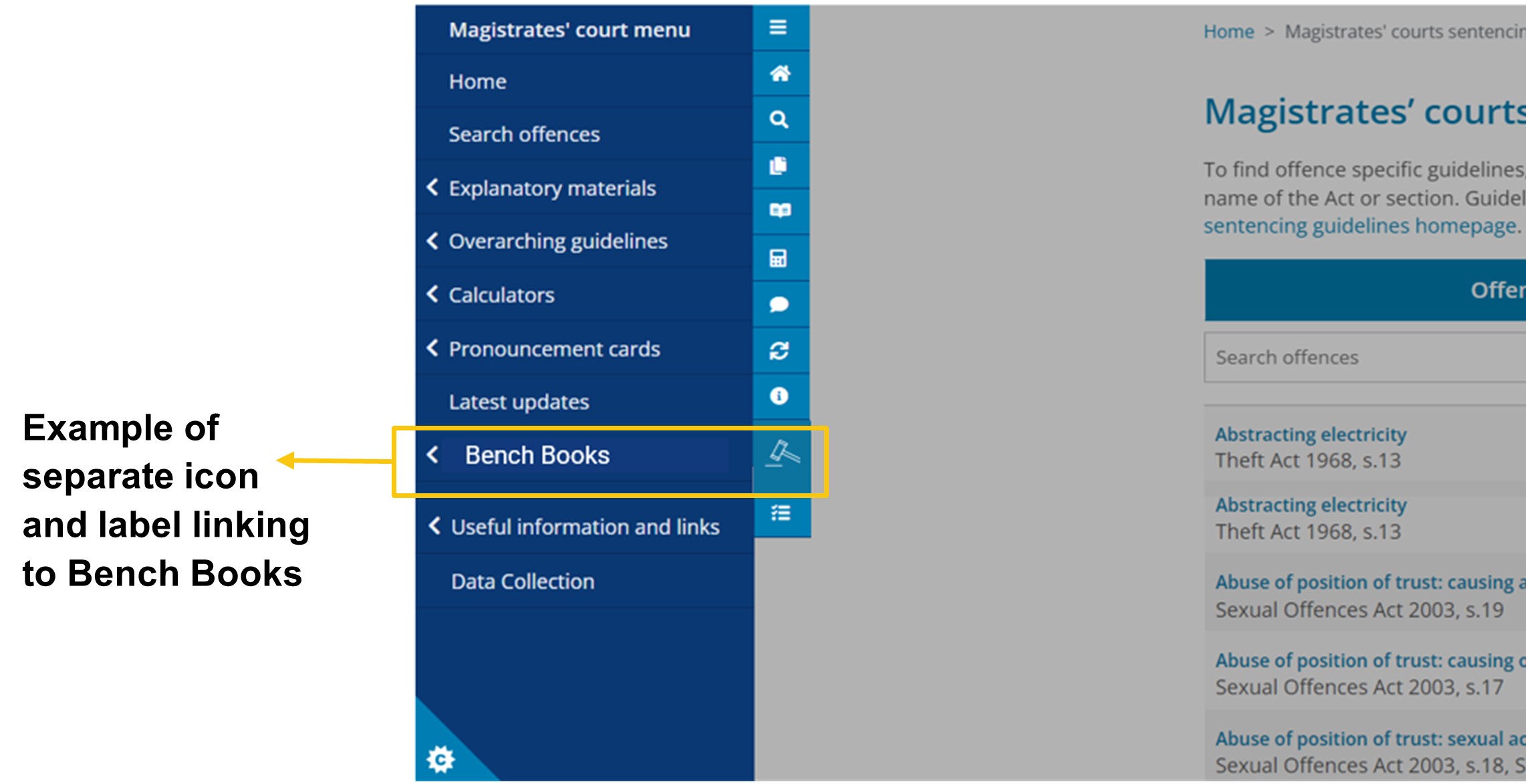

Finding C3: sentencers did not find it intuitive to locate the Bench Books on the Council’s website

Some sentencers used additional resources on the Council’s website such as the Adult Court Bench Book and Equal Treatment Bench Book to inform their sentencing. However, sentencers did not find them easy to locate. For example, the Bench Books can be accessed in the magistrates’ court guidelines via the sidebar through the icon ‘useful information’. However, when shown, sentencers were surprised to find the Bench Books available through this icon.

Recommendation C3: refine the blue sidebar to include a separate icon which makes it clearer this links to the Bench Books.

Priority: low

Rename the icon in the blue sidebar (which currently links to the adult, youth and Equal Treatment Bench Books) to be more descriptive. For example, this icon should be titled ‘Bench Books’. An example of how this recommendation could (partially) be implemented is illustrated in Figure 39.

Figure 39: Mocked up example of recommendation C3

Finding C4: some sentencers, especially those with lower levels of digital confidence, found it difficult to navigate between multiple offence specific guidelines and other resources

Some sentencers found it helpful to open relevant offence specific guidelines ahead of their court sessions. However, this often resulted in multiple tabs being open in the same window if more than one guideline needed to be referenced. Switching between these tabs was reported to be time consuming and often required clicking into a tab to see whether it was the relevant guideline.

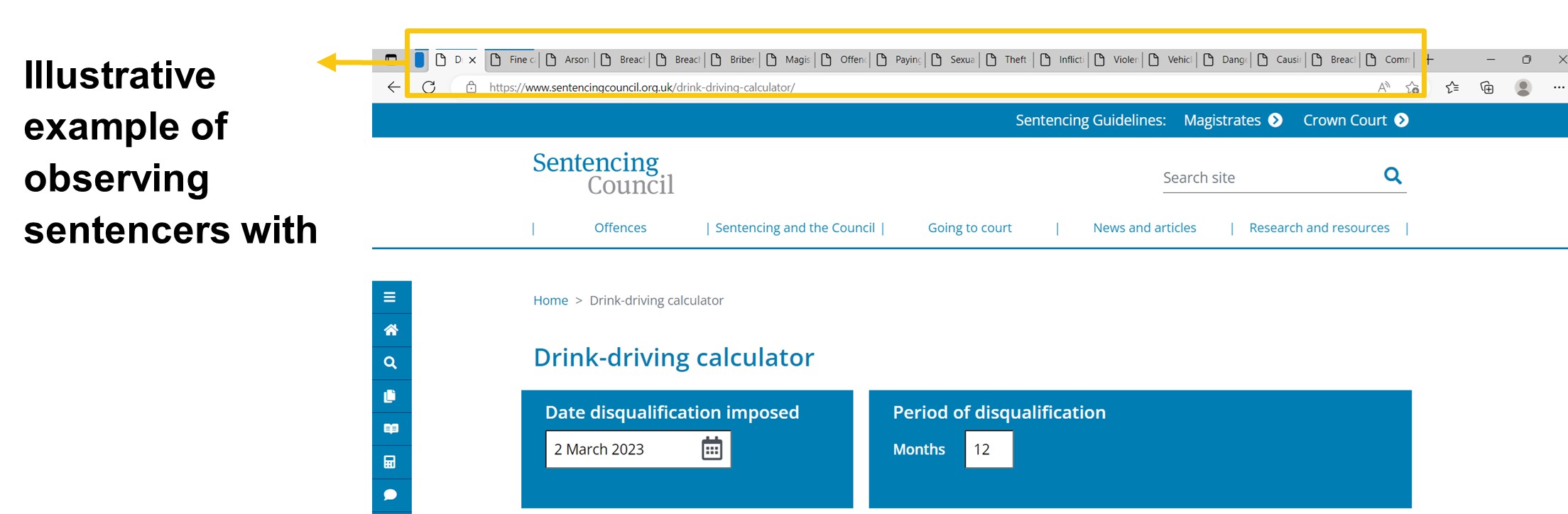

Figure 40: Illustrative example of observing sentencers with multiple tabs open of different guidelines and other resources

This may have also been influenced by individuals’ levels of digital literacy, as some sentencers were not confident using multiple tabs to access different web pages. For example, one sentencer noted they would like to view two separate guidelines side-by-side but did not think this could be done “unless you were a technical whiz”. Another sentencer was observed viewing only one guideline at a time, as they did not know how to open different guidelines in separate tabs.

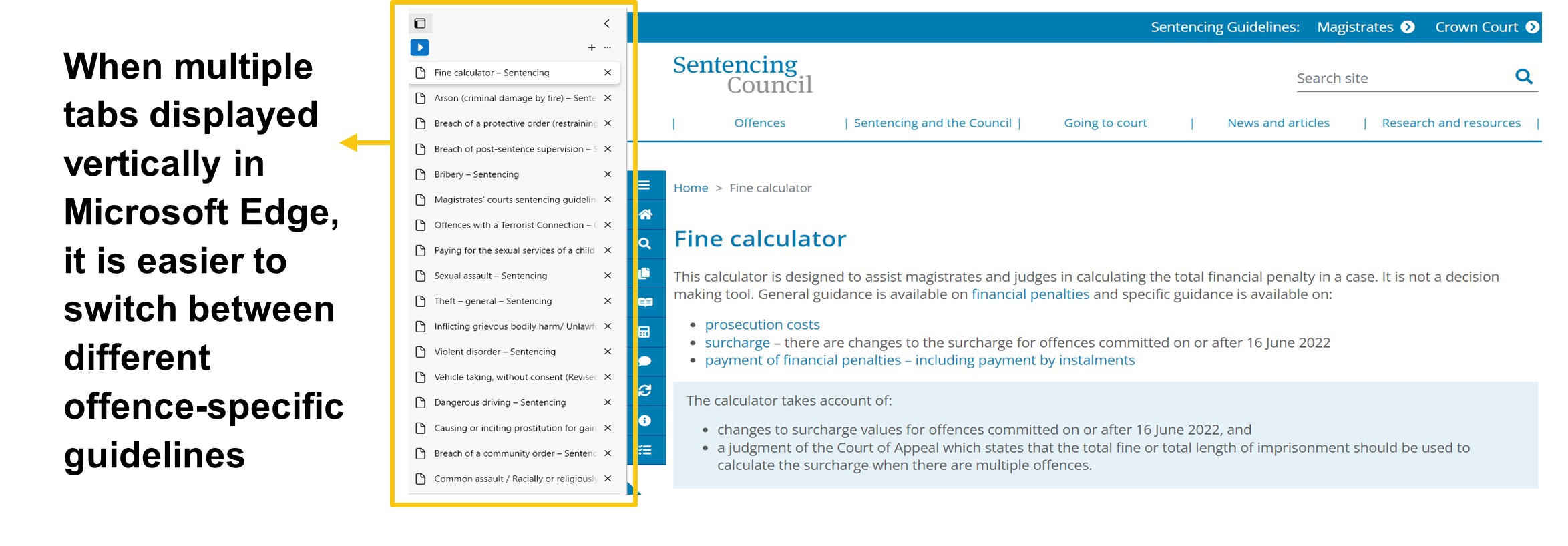

Conversely, some sentencers arranged their tabs vertically in Microsoft Edge. This was observed to more clearly list the names of offence specific guidelines for each opened tab. This appeared to make it easier for them to navigate between multiple tabs.

Figure 41: Illustrative example of observing sentencers using vertical tabs to view and access multiple guidelines and other resources

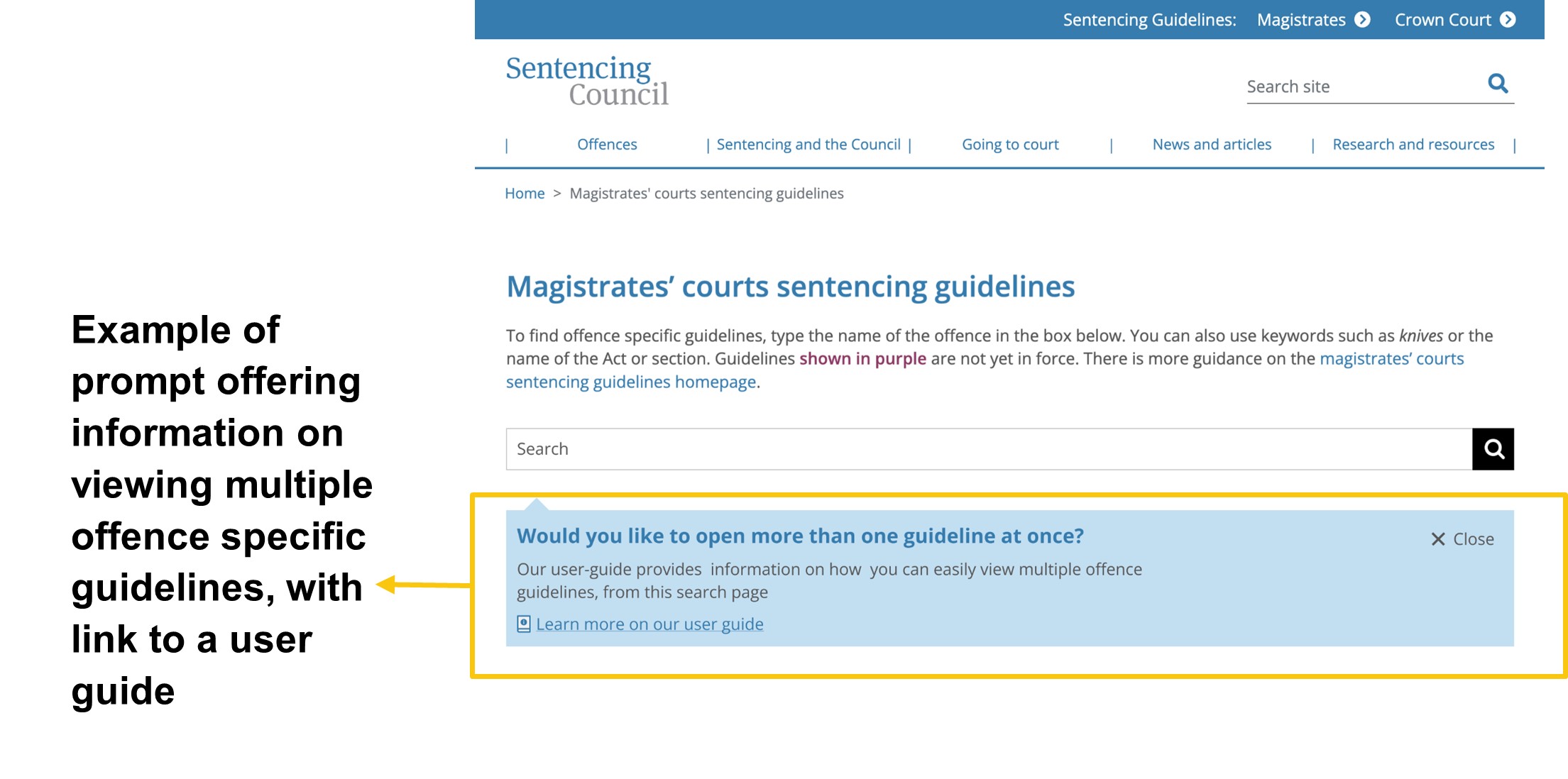

Recommendation C4: provide prompts with optional guides, to help sentencers who are not confident in their digital skills to better navigate the guidelines.

Priority: medium

The Council should provide prompts with optional guides at points where sentencers with lower confidence in their digital skills may struggle to use the website intuitively. For example, providing a prompt asking ‘would you like to open guidelines in a new tab?’ when sentencers run a search. This should allow sentencers to view a brief guide on using multiple tabs. The guides should provide specific advice with short video clips and accompanying text where appropriate.

These prompts should be automatically opened when sentencers access the offence specific search page. To avoid being seen as annoying or irrelevant to sentencers, these prompts should only be available for a relatively short time period (e.g. one week), though could also be presented again at a later date (e.g. six months later).

These prompts could also refer to guides about changes made as a result of this research project. This would support a smooth adjustment period for sentencers, as changes are made to the guidelines.

Figure 42: Mocked up example of recommendation C4

Finding C5: some sentencers had difficulty navigating to the table with starting points for compensating physical and mental injuries

Some sentencers described that they found it relatively easy to access other commonly used resources on the Council’s website (e.g. the fine calculator and pronouncement cards).

However, there were some who were observed struggling to find the tables with suggested starting points for compensating physical and mental injuries. They also stated they had difficulty locating this information quickly. These sentencers were also observed being unsure of where this information was located in the Council’s website.

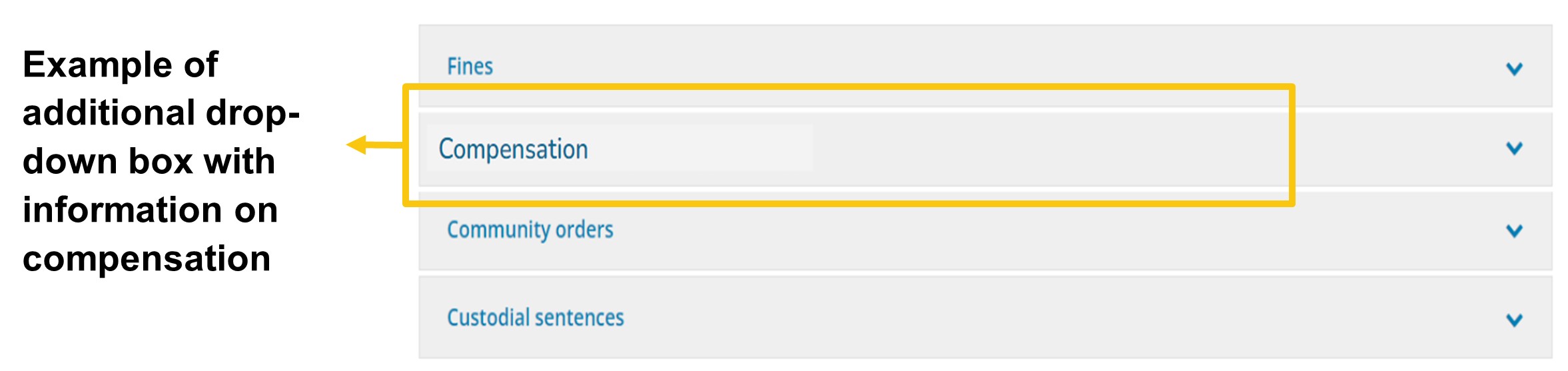

Recommendation C5: embed information about compensation within offence specific guidelines.

Priority: low

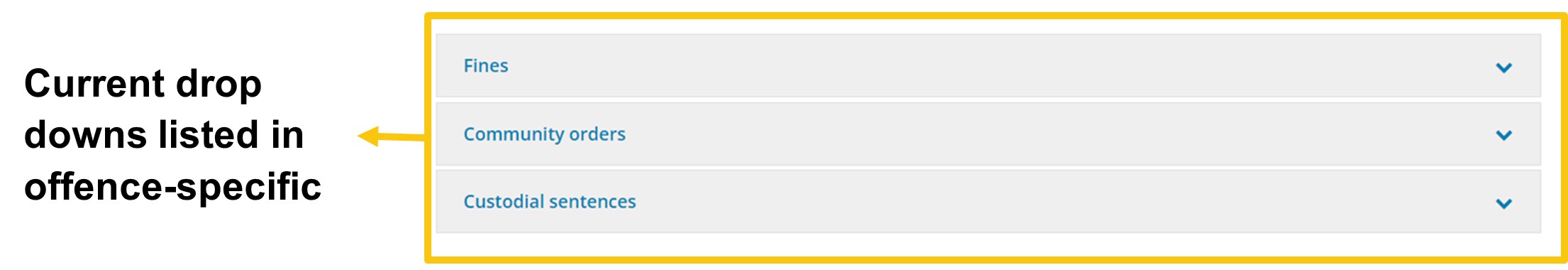

Similar to how fines are presented within the offence specific guidelines, a separate dropdown box with information about compensation should also be embedded within offence specific guidelines. This information should also provide a hyperlink to the explanatory materials section on compensation, for sentencers to refer to additional information if needed.

If practical, the Council could also consider providing this only in offence specific guidelines which relate to offences in which victims likely suffer physical or mental injury (e.g. common assault).

Alternatively, the Council could consider including a hyperlink directly to the suggested starting points for physical and mental injuries page within the offence specific guidelines. While some offence specific guidelines currently provide a link to the Introduction to compensation page, at step 7 of these guidelines, it may be beneficial to have a separate link to the suggested starting points for physical and mental injuries page.

An example of how this recommendation could be implemented is illustrated in Figure 43.

Figure 43: Comparison image of dropdowns for fines, community orders and custodial sentences, currently listed on offence specific guidelines

Figure 44: Mocked up example of recommendation C5

D. How do sentencers access the guidelines?

Finding D1: The landing page varies for magistrates depending on how they reach the guidelines

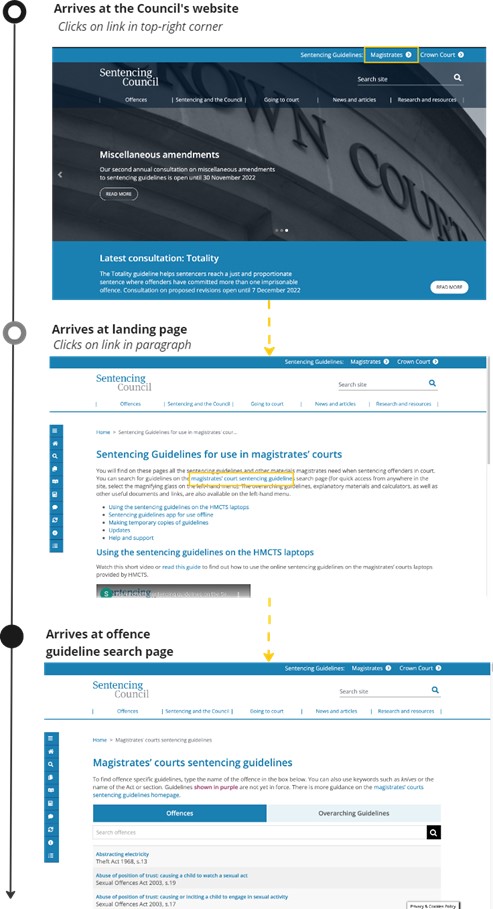

Routes to the sentencing guidelines for the magistrates’ court can take magistrates to one of two pages.

The magistrates’ court guidelines have a dedicated landing page as well as the offence specific guidelines search page. Magistrates land on either page, depending on which shortcut or link they are following. The offence specific guidelines search page was consistently considered to be the main page magistrates wanted to get to in order to access the guidelines.

When accessing the guidelines from the desktop shortcut on a court laptop, magistrates reached the offence specific guideline search page. However, when accessing the guidelines from the shortcut on the eJudiciary homepage, or through a link on the home page of the Council’s website, magistrates reached the magistrates’ sentencing guidelines homepage. This required an additional click for magistrates to reach the offence specific guidelines search page, as illustrated in Figure 45. Magistrates suggested they would prefer that all shortcuts to the guidelines landed on the offence specific guideline search page.

Figure 45: User journey to access magistrates’ court guidelines search page, via landing page

Recommendation D1: work with HMCTS to ensure all shortcuts or links to the magistrates’ guidelines consistently bring sentencers to the offence guideline search page.

Priority: low

All icons and shortcuts to the sentencing guidelines for the magistrates’ court should link directly to the offence specific guidelines search page (for the magistrates’ court).

E. How do sentencers use the guidelines when making sentencing decisions?

Finding E1: sentencers use the offence specific guidelines to inform their decision-making, but do not always physically look at the guidelines in each case (as they report they are familiar with the content of these guidelines)

Under the Sentencing Code, courts are bound to follow sentencing guidelines that are relevant to the case before them unless it is contrary to the interests of justice to do so. How sentencers use the Council’s website is therefore important to those making sentencing decisions, but how sentencers use the guidelines can vary.

When sentencers were familiar with the offences in a case, they did not always look at the corresponding guidelines, and would rely on their understanding and recollection of the information within the guidelines. They expressed confidence about knowing the information contained in the guidelines, to allow them to make an appropriate sentencing decision. While they were more likely to refer to guidelines when dealing with offences that they were less familiar with, this does pose a risk that they may not be aware of updates to offence specific guidelines.

Sentencers (particularly magistrates) reported that they tended to prepare for their working day by opening the offence specific guidelines that were relevant to all their upcoming cases for that day. Magistrates said that they generally did not have time to review these guidelines before sitting in court but would have them open on their court laptops to be able to refer to these when dealing with cases. Magistrates also referred to some explanatory materials (particularly the fine calculator), when making sentencing decisions whilst sitting in court.

Although magistrates typically did not review the overarching guidelines when sitting in court, mostly due to time constraints, they did state they would look at the information in overarching guidelines if they were dealing with a more complex case. This usually involves taking time to deliberate the case in retiring rooms, where they would be able to review offence specific and overarching guidelines. In addition, most magistrates noted they were generally aware of the information contained within the overarching guidelines.

Judges were more likely than magistrates to review the guidelines before sitting in court to form a view about their sentencing decision. This was partially due to having more time available before sitting in court to deal with cases. Similarly, judges were more likely than magistrates to refer to the overarching guidelines, given they may have more time to prepare for a case. Additionally, judges may be dealing with more complex cases which requires referring to the overarching guidelines more frequently. Judges would also refer to the sentencing guidelines whilst sitting in court. They also referred to other professional judicial resources (e.g. Archbold, Sentencing Referencer) to seek additional sentencing information, more than the information on the Council’s website.

Recommendation E1: communicate more directly with sentencers when guidelines are revised and encourage sentencers to review changes

riority: medium

The Council should send an email alert to all sentencers when the contents of an offence specific guideline is updated or changed.

Additional findings and suggestions

A high-level review of the offence specific guideline pages was conducted, using the Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool (WAVE). The WAVE tool is designed to identify elements within web pages that might not align with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). The WCAG provide guidance on how information should be published on the internet, to be more easily accessible to people with different levels of ability (e.g. visual, learning or physical abilities).

Three main findings were identified, relating to the way icons and colour contrast was presented within offence specific guidelines. These findings may also be applicable to other guidelines and pages on the Council’s website which have the same design features as the offence specific guidelines.

Icons

Finding 1: icons and links within the guidelines were not always labelled

Links or icons which do not have accompanying text can introduce confusion for keyboard and screen-reader users. The blue sidebar in the offence specific guidelines does not automatically present with accompanying text to users of the guidelines (see Figure 46).

Figure 46: Examples of icons in blue sidebar and link to print guideline, without accompanying text labels

Suggestion: embed relevant descriptive text for icons and links within the offence specific guidelines pages.

For icons in the blue sidebar, this suggestion could be incorporated within Recommendation C1 (embedding the blue sidebar at the top of the guidelines page).

Finding 2: icons within the blue sidebar appear to be smaller than recommended by accessibility standards

The size of icons within the blue sidebar appear to be smaller than the recommended size for icons (44 x 44 pixels), as suggested by the WCAG 2.1.

Suggestion: increase the size of icons displayed on the guidelines, to at least 44×44 pixels.

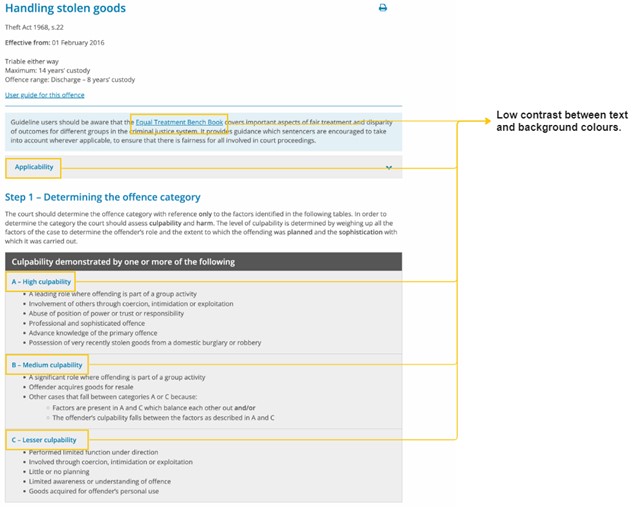

Colour contrast

Finding 1: low colour contrast exists between text and background colours in sections of text within the offence specific guidelines

Text that has low colour contrast with its background colour can make it difficult for people with colour sensitivity or other visual conditions to read information. Text (or other elements) within a webpage should be sufficiently distinguishable in contrast to the background.

Figure 47: Examples of low colour contrast within the offence specific guidelines, as identified by WAVE

Suggestion: increase the colour contrast of text in the offence specific guidelines, to increase accessible visibility.

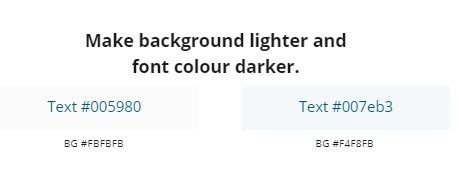

The colour contrast of offence specific guidelines should be increased. This can be achieved by using darker font colours and maintaining the current background colours (see Figure 48). Alternatively, a lighter background colour could be used, in addition to making the font colour slightly darker (see Figure 49).

Figure 48: Examples of higher colour contrast using existing background colours

Figure 49: Examples of higher colour contrast, with different background and font colours

5. Conclusion

Sentencers are generally satisfied with the usability of the guidelines, with the exception of the search function. Difficulties and frustrations with the search function on the offence specific guidelines page was a common barrier to the usability of the guidelines. These difficulties take up sentencers’ time and can distract them from engaging in other tasks in a timely manner. Almost all of the high-priority recommendations made in this report relate to improving the search function.

A total of 18 recommendations have been made in this report, of which there are:

- five high-priority recommendations

- nine medium-priority recommendations

- four low-priority recommendations

In addition to improving the search function, these recommendations aim to support sentencers by making it easier to navigate the guidelines and access different kinds of information. This includes presenting the guidelines in a more intuitive manner, aligning with how sentencers use the guidelines on a daily basis. It also involves providing ways to support sentencers finding and understanding sentencing information in a smooth and user-friendly manner.

The sentencing guidelines support sentencers with a consistent approach to sentencing. The benefit of a clear and consistent structure for the guidelines was commended by many sentencers in this project. Continuing to improve the usability of the guidelines will further help both sentencers and the Council strive towards a transparent and consistent approach to sentencing.