1. Introduction

The Sentencing Council was set up in 2010 and produces guidelines for use by all members of the judiciary when sentencing after conviction in criminal cases.

One of the Sentencing Council’s statutory duties under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 is to monitor the operation and effect of its sentencing guidelines and to draw conclusions from this information. This evaluation will examine the potential impact and implementation of the Bladed articles and offensive weapon offences guidelines, describing the research and analysis that has been undertaken and exploring whether there is any evidence of any implementation issues with the guidelines.

The evaluation will also assess whether any changes anticipated by the resource assessments, which were published alongside the guidelines, have occurred or whether there have been any unanticipated impacts. The findings are discussed, and possible interpretations and next steps are presented.

Bladed article and offensive weapon offences are relatively high-volume offences and are covered by three sentencing guidelines, which came into force on 1 June 2018:

- Bladed articles and offensive weapons – possession (adults only), hereafter referred to as the ‘Possession’ guideline.

- Bladed articles and offensive weapons – threats (adults only), hereafter referred to as the ‘Threats’ guideline.

- Bladed articles and offensive weapons (possession and threats) – children and young people (only applies to the sentencing of offenders aged under 18), hereafter referred to as the ‘Children and young people’ guideline.

It is worth noting that whilst this evaluation refers to the ‘Possession’ guideline, the actual guideline was renamed in 2023 to ‘Bladed articles and offensive weapons – having in a public place’. The guideline title was changed as the word ‘having’ rather than ‘possession’ better reflects the wording in the legislation creating the offence. The evaluation continues to use the term ‘possession’ as this was the term used to describe the guideline during the period that has been considered for analysis for this evaluation.

1.1. Possession guideline

The adult Possession guideline covers five offences:

- possession of an offensive weapon in a public place

- possession of an article with blade/point in a public place

- possession of an offensive weapon on education premises

- possession of an article with blade/point on education premises

- unauthorised possession in prison of a knife or offensive weapon

These offences all share a statutory maximum sentence of 4 years’ custody and, for the time period analysed, all of them (except unauthorised possession in prison of a knife or offensive weapon) were subject to a statutory minimum sentence provision of 6 months’ custody for a second or further relevant offence, except in particular circumstances. More information on this provision for all three guidelines can be found in section 1.4.1.

The Possession guideline has four levels of culpability (A, B, C and D) and two levels of harm (1 and 2), leading to an eight-point sentencing table. It has a range of starting points from a low level community order for the lowest offence category D2, up to 1 year 6 months’ custody for the most serious category A1 offences. The top of the category range for A1 in the guideline is 2 years 6 months’ custody and the bottom of the range for D2 is a band C fine.

This guideline replaced previously published guidelines from the Sentencing Guidelines Council (SGC) relating to adult offenders at the magistrates’ courts only, which came into force in August 2008. By contrast, the Sentencing Council guideline also applies to sentencing at the Crown Court. The original SGC guideline had only three offence categories. Sentencers were advised that a starting point of at least 12 weeks’ custody would be appropriate for offences involving possession of a bladed article, as opposed to an offensive weapon. This guidance reflected the judgment in R v Povey [2008] EWCA Crim 1261; [2009] 1 Cr App R (S) 42, which drew attention to the prevalence and recent escalation of knife crime offending and highlighted the importance of the role of sentencing in reducing these crimes (including reduction by deterrence) and the protection of the public.

By comparison, the updated Possession guideline specifies that possession of a bladed article or ‘highly dangerous’ offensive weapon falls into culpability A, where the lowest starting point for cases of category 2 harm is 6 months’ custody. As such, it was expected that any offences involving possession of a bladed article/highly dangerous offensive weapon would likely receive a custodial sentence of between 3 months and 2 years 6 months (the top and bottom of the category ranges), before any reductions for a guilty plea. However, there is provision made within culpability D for if ‘possession of weapon falls just short of a reasonable excuse’, where the starting point for both harm levels 1 and 2 is a community sentence. Above the sentencing table, sentencers are advised that where there are characteristics present which fall under different levels of culpability, they should balance the level of culpability accordingly.

Based on current sentencing practice at the time for possession offences, the resource assessment that accompanied the definitive guideline anticipated that there might be a potential increased demand on prison and probation resources resulting from a higher proportion of offenders receiving a custodial sentence under the new guideline for possession of a bladed article. Previously, a relatively high proportion of offenders (32 per cent in 2016) received a non-custodial sentence for these offences. Under the new guideline it was anticipated that these offenders might receive a short custodial sentence instead. However, it acknowledged that sentence severity had been increasing over the past decade and so any increases in the average custodial sentence length (ACSL – see Annex A for more details) and custody rate after the introduction of the guideline might similarly be a continuation of a pre-existing trend. It also stated that there may be an increase in the number of offenders receiving custodial sentences for a second or subsequent offence, as per the change in legislation, but that this impact would not be due to the guideline itself.

1.2. Threats guideline

The adult Threats guideline covers three offences:

- threatening with an offensive weapon in a public place

- threatening with an article with a blade/point in a public place

- threatening with an article with a blade/point or offensive weapon on education premises.

These offences all share a statutory maximum sentence of 4 years’ custody, the same as possession offences. For the period of time analysed, the offences were also all subject to statutory minimum sentence provisions of 6 months’ custody except in particular circumstances where the sentencer has considered it unjust to do so. More information on this provision can be found in section 1.4.1.

The guideline has two levels of culpability and two levels of harm, leading to a much smaller four-point sentencing table in comparison with the possession guideline. There are a range of starting points from 6 months’ custody for the lowest offence category B2, (reflecting the statutory minimum sentence), up to 2 years’ custody for the most serious category A1 offences. The top of the category range for A1 offences is 3 years’ custody, a little higher than the Possession guideline. Unlike the Possession guideline, there are no non-custodial sentences presented in any of the ranges.

The resource assessment anticipated that there would be no impact on prison and probation resources as a direct result of the guideline. It acknowledged that the new guideline reflected the legislation regarding the statutory minimum and so any increase in the number of offenders receiving custodial sentences would instead be the impact of the legislation.

1.3. Children and young people guideline

The Children and young people guideline directs sentencers to consider it alongside the Overarching principles – Sentencing children and young people guideline. This provides sentencers with comprehensive guidance on the distinct principles and welfare considerations that should be held in mind when sentencing children and young people more generally. The offence specific guideline was the first guidance available to the courts for sentencing children and young people specifically convicted of offences of bladed articles and offensive weapons, beyond the overarching principles which came into force one year prior.

The format of this guideline differs considerably from the adult guideline, reflecting the substantial differences in sentencing this age group of offenders, namely that the principal aim in the sentencing of children and young people is to prevent offending and reoffending and to have regard for their welfare. This is evident in the different range of sentencing outcomes available to courts to address the needs of these individuals, such as referral orders and youth rehabilitation orders (YROs). Detention and training orders (DTOs) are additionally available as a type of custodial sentence in the most serious cases. The aims of any custodial sentence for children and young people should be to provide training and education with the specific intent of diverting the individual away from criminality and to reduce reoffending and provide rehabilitation. These sentences can be spent in secure children’s homes, secure training centres and young offender institutions.

Following the structure of the offence specific sentencing guidelines produced previously for sentencing children and young people for robbery and sexual offences, the structure of the Bladed articles and offensive weapons (possession and threats) – children and young people guideline sets out that sentencers should first assess the seriousness of the offending by considering the nature of the offence at step 1, followed by an assessment of the relevant aggravating and mitigating factors at step 2. This non-exhaustive list of factors shares some commonalities with the adult guideline, such as aggravation for attempts to conceal identity and mitigation for cooperation with the police. However, it also contains some more targeted factors such as aggravation for deliberately committing the offence before a group of peers with the intent of causing additional distress, and mitigation for being in education or having an unstable upbringing.

The guideline also incorporates (at the time, recently imposed) specific statutory minimum sentence provisions, which vary depending on the offence they were convicted of. More information on this provision can be found in section 1.4.1. When sentencing young people who were aged 16 or over on the date of the offence for possession of a bladed article or offensive weapon in a public place or on education premises, the court must impose a sentence of at least 4 months’ DTO where this is a second or further relevant offence, unless the court is of the opinion that there are particular circumstances (where offence committed before 28 June 2022) which make it unjust in all the circumstances to do so. When sentencing young people aged 16 or over at the date of conviction for threatening with a bladed article or offensive weapon, the court must impose a sentence of at least 4 months DTO, again, unless the court is of the opinion that there are particular circumstances which make it unjust to do so in all the circumstances (‘exceptional circumstances’ after 28 June 2022).

The resource assessment for children and young people that was published alongside the guideline set out that there was no intention to change sentencing practice, but rather the aim was to produce a useful and accessible guideline which would promote a more consistent approach to sentencing, especially in light of the legislative changes setting out the minimum sentence provisions. The Council did not anticipate a substantial impact on youth justice services as a result of the guideline. Given the particular focus on offender personal mitigation within the guideline, it was not expected to increase the proportion of children and young people receiving a custodial sentence for these offences. It did, however, acknowledge that there could be increases in the number of offenders receiving DTOs for threats or for a second or subsequent offence of possession, but that these would be the impact of the legislation, rather than the sentencing guideline.

1.4. Overarching issues

1.4.1. Statutory minimum sentence

All three guidelines are subject to statutory minimum sentence provisions. These are outlined in each guideline within a dedicated step. Across all three, the legislation previously outlined that the court must impose this minimum sentence unless it is of the opinion that there are “particular circumstances” relating to the offence or the offender “which make it unjust to do so in all the circumstances”. This wording applied to offences committed before 28 June 2022.

For the Possession guideline, the legislation is referenced at Step 3 in the guideline. This legislation previously set out that where a possession offence is being sentenced and it is the offender’s second or further relevant offence, the court must impose a sentence of at least 6 months’ imprisonment. The ‘relevant offences’ that are referenced include the four possession offences for which this statutory minimum sentence applies, and all threat offences.

In the Threats guideline, also outlined at Step 3, the minimum term is that the court must impose a sentence of at least 6 months’ imprisonment for an offence of threatening with a bladed article or offensive weapon.

Lastly, the Children and young people guideline also references the statutory minimum sentence provisions at Step 5 of the guideline. For the individuals who meet the criteria, the guideline highlights that the court must impose a sentence of at least a 4 month DTO for all threat offences, or where this was the second or further relevant offence for a possession offence.

The ‘unjust in all the circumstances’ exemption wording applicable to all of these offences has since been updated in legislation under the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 (PCSC Act 2022) and subsequently amended in the guidelines. This change means that for offences committed on or after 28 June 2022, the statutory minima must be applied for a second or further relevant offence when sentencing a possession offence, or when sentencing all threat offences, unless the court is of the opinion that there are ‘exceptional circumstances’ which relate to the offence or to the offender, that would justify not doing so.

However, it should be noted that during the relevant time period for which data were analysed for this evaluation, the ‘unjust in all the circumstances’ rather than ‘exceptional circumstances’ was the wording of the exemption in the guideline. Therefore, the scope of this evaluation only covers the implementation of the original wording and does not attempt to evaluate the strengthened language under the PCSC Act. This means that the utility of any conclusions in this review in relation to this element of the guidelines may be limited.

1.4.2. Weapon categorisation

In all of these guidelines, the severity of the weapon involved is an important consideration within the assessment of culpability. To assist sentencers in this, the guidelines contain some guidance regarding the classification of any weapons involved.

The top culpability category of both adult guidelines and the list of factors within the children and young people guideline which may justify imposing a custodial sentence or stringent youth rehabilitation order all refer to a ‘bladed article’ and a ‘highly dangerous’ offensive weapon.

The guideline explains that highly dangerous offensive weapons are those whose dangerous nature is substantially above the legal definition of an offensive weapon, which is ‘any article made or adapted for use for causing injury, or is intended by the person having it with him for such use’. The guideline draws sentencers’ attention to this, but it is then left to the court to determine whether the weapon involved is highly dangerous, based on the facts and circumstances of the case.

Regarding the definition of a bladed article, this is set out in legislation and includes any article which “has a blade or is sharply pointed except a folding pocketknife, unless the blade of the folding pocketknife exceeds 3 inches (7.62cm)”.

2. Approach

2.1. Aims

This evaluation aims to fulfil the Council’s statutory duty to monitor the operation and effect of its sentencing guidelines and to draw conclusions from this information, by considering the available evidence.

It explores whether sentencing outcomes changed following the introduction of the guidelines and how any observed impacts compare with what was anticipated. It also examines whether there is any evidence of issues with the implementation of the guidelines, especially with regards to the application of the statutory minimum sentence (where applicable), and the weapon categorisation.

2.2. Methodology

The Council has taken a mixed methods approach to this evaluation, considering the available evidence from multiple different sources, each with their own strengths and limitations, which are set out as follows.

2.2.1. Analysis of CPD trend data

The Ministry of Justice’s Court Proceedings Database (CPD) was used to produce descriptive statistics for the relevant bladed article and offensive weapon possession and threat offences covered by the guidelines. For more information on this data source, please see Annex A at the end of the report. Any changes in the sentences being imposed and the ACSL between the 12 month period before the guidelines came into effect (March 2017 to February 2018) and the 12 months after the guidelines came into effect (June 2018 to May 2019) were examined.

However, a comparison of sentencing outcomes and ACSLs between only the pre and post guideline period would not take account of any fluctuations in the average severity of sentencing over time. These may be due to changes in sentencing practice which are unrelated to guidelines, such as the changing number and seriousness of cases coming before the courts or any changes in charging practice. The data were therefore also used to conduct trend analysis for the period 2011 to 2021 inclusive, which was the latest period of data available when this analysis was undertaken.

While the CPD data provide a comprehensive picture of sentencing practice for the offences over the relevant period, this source of evidence cannot be used to understand the drivers behind any changes in the distribution of sentence outcomes or ACSLs. This is because the data do not contain any details about some of the guideline factors that sentencers applied to the cases (e.g. those covering harm, culpability, aggravation and mitigation) and therefore the type of factors that influenced their decision making. This source also cannot be used to assess the implementation of the guideline particularly with regards to the weapon categorisation, as this information is also not recorded in the administrative courts systems.

In addition, in considering the CPD evidence for the Children and young people guideline, it is important to note that the age variable in the data is the age of the offender at the date of sentence. This means there may be some individuals who appear in the data as aged 16 who were in fact not yet aged 16 when they committed the offence or when they were convicted.

2.2.2. Analysis of survey data

In order to fill the evidence gaps identified above, a data collection exercise was undertaken both before and after the guideline came into force, in all magistrates’ courts in England and Wales where possession of a bladed article or offensive weapon was the principal offence. For a definition of ‘principal offence’, please see Annex A. Threat offences were excluded from this exercise as volumes sentenced at magistrates’ courts for these offences were too low for it to be meaningful. The data collection focussed on magistrates’ courts as this was considered to be a key data gap as, unlike the Crown Court, sentencing transcripts are not available and offence volumes were sufficiently high for this approach.

Sentencers were asked to complete a survey form, mainly online, for every offender sentenced between 1 November 2017 and 30 March 2018 for the pre guideline period, and between 23 April 2019 and 30 September 2019 for the post guideline period. A small number of paper forms were circulated and filled in for the pre-guideline data collection, in an attempt to boost response rates, but the post-guideline collection was fully administered online via the Council’s website.

The survey asked sentencers to provide detailed information following the structure of the guideline in place at the time, including the relevant culpability and harm factors that they took into account, the offence categorisation, any relevant aggravating and mitigating factors they considered, details of any guilty plea, the final sentence imposed and what they regarded as the ‘single most important factor’ affecting the sentence. Many of these guideline specific details are not available from the CPD.

The response rate for this survey was 16 per cent for the pre guideline period, with 411 full responses in total – 48 on paper and 363 online – and 34 per cent for the post guideline period, with 928 full online responses.

While these data are able to provide a more in-depth understanding of the reasons behind the sentence imposed, they will only represent a sample of all types of offences and cases being sentenced for possession offences, so any findings should be interpreted with caution. Any findings will also be skewed towards the lower end of sentencing severity as the data only cover sentencing at the magistrates’ courts for these offences. In addition, given the response rate post guideline was more than double that for pre guideline, the post guideline data may be more representative of magistrates’ court sentencing for possession offences.

Nevertheless, the data collected from this survey could be analysed to understand how the guideline is being used by sentencers, for example the relationship between the relevant culpability and harm factors and the offence categorisations chosen by the sentencer. These survey data also permitted the examination of specific implementation issues, such as the application of the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody for a second or further relevant offence.

2.2.3. Content analysis of sentencing remarks

A content analysis of a small sample of Crown Court judges’ sentencing remarks of adult offenders sentenced for both possession offences (n=30) and threats offences (n=26) was undertaken for the post guideline period only, to examine if there was any evidence of implementation issues with the guidelines.

The aim of this transcript analysis was to gain an insight into how Crown Court sentencers are sentencing these offences and using the guidelines in practice. Particular attention was given to the offence categorisation selected by the sentencer based on the weapon involved, and the application of the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody for a second or further relevant possession offence, or for offences of threatening with a bladed article or offensive weapon.

A limitation of this source is that transcripts of sentencing remarks are not available from magistrates’ courts, so any evidence is likely to be skewed towards the higher end of sentencing severity for these offences. There also were constraints around the number of transcripts that could reasonably be analysed, given that the process is resource intensive. As such, these data represented only a reasonably small sample of sentencing practice for these offences.

2.2.4. Analysis of criminal appeals data

A content analysis of a sample of sentencing remarks of Court of Appeal judgments in the post guideline period (from 1 June 2018 onwards until the end of 2021), was also undertaken to support an assessment of the implementation of the adult Possession guideline. The sample ordered included those appeals which were ‘allowed’ (appeal successful) and ‘dismissed’ in the period.

These transcripts were examined in order to understand the reasons put forward for appealing against these sentences, and whether any of these reasons alluded to implementation or consistency issues regarding the use of the guideline by sentencers.

3. Offence specific findings

3.1. Possession offences

Summary of findings

- The majority of offenders received a custodial sentence for possession offences and sentencing outcomes did not change substantially following the guideline.

- The resource assessment estimated that additional prison places might be needed as a result of the guideline. While there was no evidence that this has been the case, it is acknowledged that sentencing outcomes may have been impacted by the pandemic.

- The mean and median ACSL were generally stable pre to post guideline, indicating sentencers may already have been applying the key principles regarding sentencing possession offences, particularly the statutory minimum sentence, prior to the introduction of the Possession guideline.

- The majority of knives and bladed articles cases were categorised correctly in culpability A. However, there was evidence of some balancing of culpability factors, even for cases not involving the culpability D factor ‘Possession of weapon falls just short of reasonable excuse’, especially in cases where the weapons were reportedly not used to threaten or cause fear.

- For possession of a bladed article offences, the proportion of non-custodial outcomes decreased more sharply immediately following the guideline but then plateaued.

- For possession of offensive weapons offences, there was no decrease observed in the proportion of non-custodial outcomes. Instead, there was an increase in these outcomes from 2017 onwards.

- Specifically at magistrates’ courts, as well as predominantly being categorised as low harm, the cases receiving non-custodial outcomes were found to generally involve lower culpability factors with a high proportion of guilty pleas.

- In relation to the statutory minimum sentence, the guideline appears to have maintained the low level of community sentences imposed on offenders with qualifying previous convictions.

- Sentencers seemed to place a relatively high weight on mitigation during sentencing and may have been utilising principles in the Imposition of community and custodial sentences guideline to suspend custody or impose community orders for possession offences.

3.1.1. Summary trend analysis

All possession offences

Of the five offences covered by the Possession guideline, possession of a bladed article in a public place is the highest volume, comprising almost three quarters of the around 9,800 adult offenders sentenced in 2021 for a possession offence. Possession of an offensive weapon in a public place is the second highest volume possession offence, comprising around one quarter of offenders sentenced in recent years. The remaining three offences are comparatively much less frequent: there were fewer than 10 adult offenders sentenced for both possession of a bladed article or possession of an offensive weapon on education premises in 2021, and around 100 offenders sentenced for unauthorised possession in prison.

While there are differences between offences, overall, around two thirds of all possession offences are sentenced in the magistrates’ courts. This proportion has remained stable over time and there is no evidence that this has changed since the guideline came into force on 1 June 2018. The exception is for unauthorised possession in prison of a knife or offensive weapon (which came into force as an offence on 1 June 2015) where, since 2016, the majority of offenders are sentenced in the Crown Court (79 per cent of offenders in 2021).

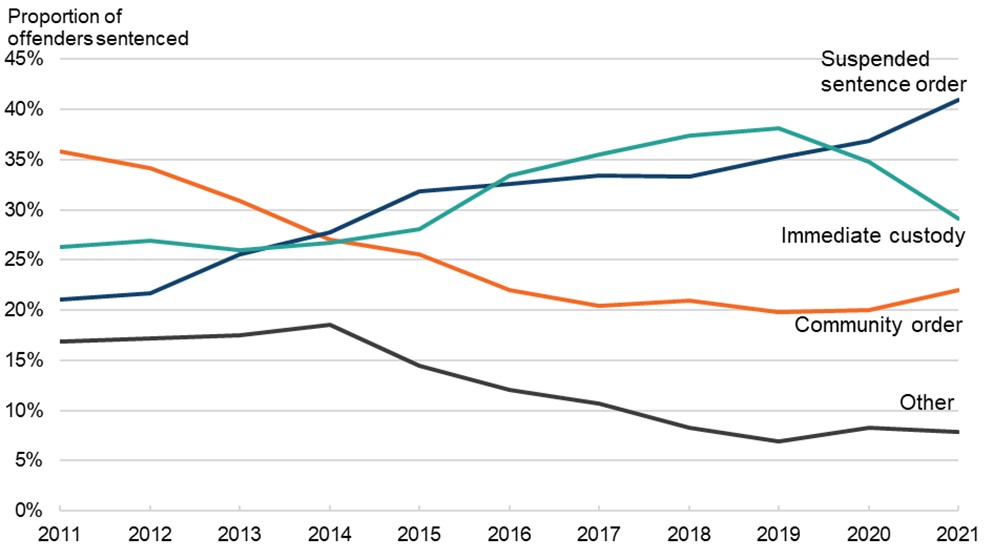

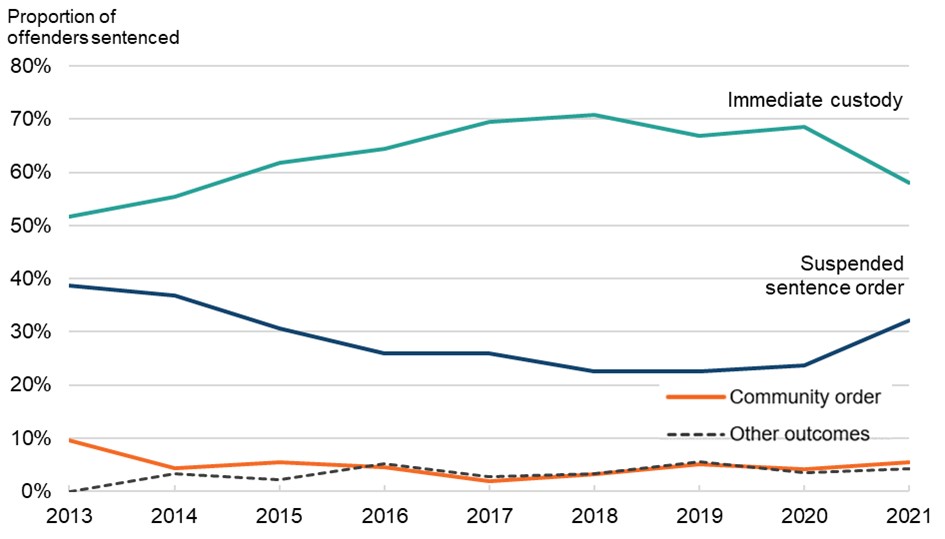

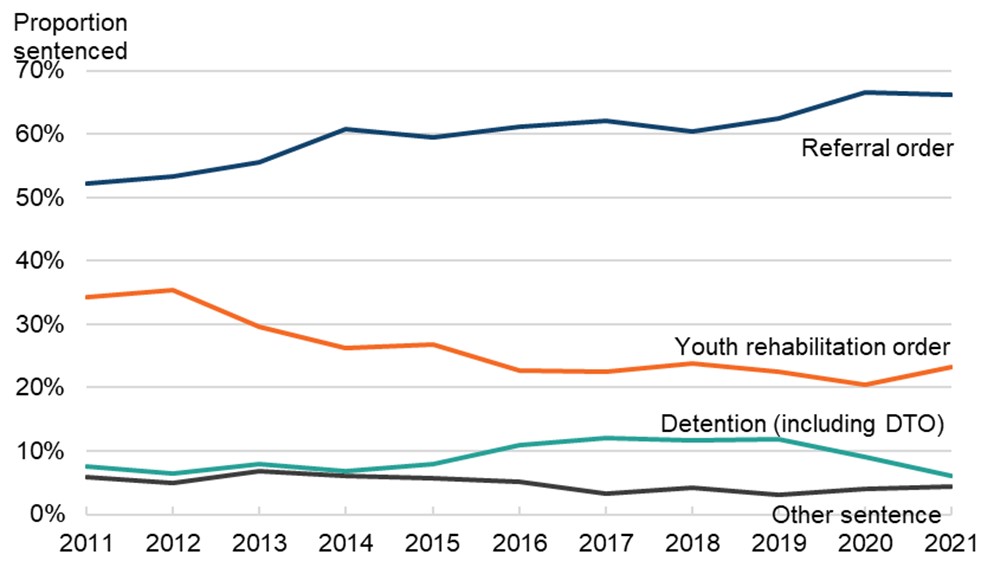

Figure 1: Sentencing outcomes for adults convicted of all possession offences, 2011 to 2021 (MoJ CPD)

Overall, for all possession offences, the most frequent outcome in 2021 was a suspended sentence order (SSO) with 41 per cent of 9,800 offenders sentenced this year receiving this outcome. The proportion of SSOs for possession offences has generally been steadily increasing over time, and this trend does not appear to have changed when the guideline came into force during 2018 (Figure 1).

The proportion of SSOs has also consistently been increasing in magistrates’ courts, where they have been the most frequent outcome for possession offences since 2016. In 2021, SSOs comprised 42 per cent of around 6,800 sentencing outcomes for possession offences in magistrates’ courts. At the Crown Court, immediate custody has been the most frequent sentencing outcome each year from 2011 to 2021, comprising almost half (46 per cent) of around 3,000 sentencing outcomes for possession offences in 2021. Overall, the trend in sentencing outcome proportions at both magistrates’ courts and the Crown Court appear unaffected by the introduction of the Possession guideline in June 2018.

This also applies to non-custodial outcomes, where the proportion for all possession offences has been broadly stable since 2017, a year pre-guideline. For those offenders receiving immediate custody for possession offences, the average custodial sentence length (ACSL) was calculated using CPD data. Comparing the 12 month period before the guideline was published with the 12 month period directly after the guideline came into force, shows a small increase in the mean ACSL pre to post guideline from 6.4 months to 6.8 months. However, when the whole time series from 2011 to 2021 is considered, this increase can be viewed in the context of a gradual increase over time, from 5.6 months in 2011 to the peak of 6.8 months in 2018, after which it appears to have stabilised.

To examine the impact and implementation of the Possession guideline in full, it has been important to analyse sentencing outcome data for the two highest volume offences separately, to explore any differences between the two offences, given the placement of weapon factors in the guideline. Any overarching themes for the impact and implementation of the Possession guideline are then subsequently presented.

Possession of a bladed article in a public place

Possession of a bladed article is the first factor within culpability A of the guideline. This has a starting point of either 6 months’ or 1 year 6 months’ custody, depending on the nature of the harm. The resource assessment anticipated that given that a high proportion of offenders were currently receiving a non-custodial sentence for possession of a bladed article, the guideline could lead to an increase in sentencing severity, as offenders previously receiving a non-custodial sentence pre guideline might be expected to receive a custodial sentence post guideline instead. This was estimated to result in the need for around 80 additional prison places per year.

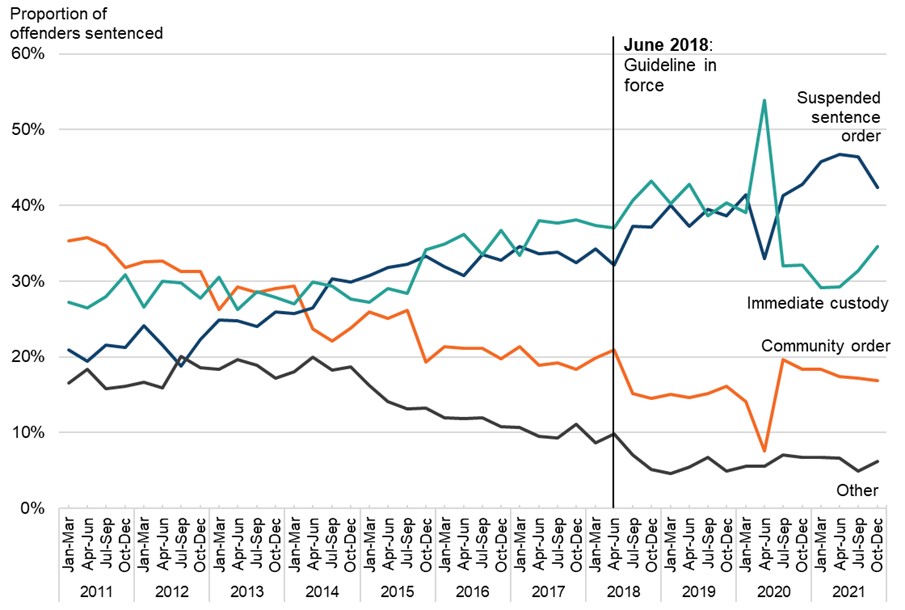

Figure 2 compares the sentencing outcomes for possession of a bladed article in a public place on a quarterly basis. Analysis of trends at this level of detail allows for more detailed exploration of the timing of certain changes. As seen, the majority of offenders receive some type of custodial sentence for this offence, and the most frequent sentencing outcome has mostly alternated between immediate custody and a suspended sentence order (SSO), both before and after the guideline.

Figure 2: Sentencing outcomes for adults convicted of possession of a bladed article in a public place, Jan-Mar 2011 to Oct-Dec 2021 (MoJ CPD)

Before the guideline came into force, the proportion of SSOs had been reasonably stable at around one third of sentencing outcomes for several years. Over the same time, there was an increase in the proportion of immediate custodial outcomes, from 27 per cent in the period January-March 2015 to 37 per cent by April-June 2018. Throughout 2017, the year before the guideline came into force, a slightly higher proportion of offenders received immediate custody than an SSO. However, after the guideline came into force, the proportion of SSOs increased and the trend for immediate custody plateaued, and more offenders began to receive an SSO than immediate custody.

Since the spike in early 2020, which is assumed to have been driven by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic prioritising the most serious cases in courts, the proportion of immediate custodial outcomes has generally decreased. In 2021, almost half of adult offenders sentenced for possession of a bladed article received an SSO and fewer than one third received immediate custody. It is possible these trends are driven by the ongoing impact of the pandemic.

Regarding non-custodial sentences, the proportion of community order (CO) and other sentence outcomes had already been decreasing before the guideline came into force in June 2018. Immediately after the guideline came into force, there was a short period of an apparent sharper decline in CO outcomes. However, contrary to expectations, this was then followed by an increase again and then a general plateau in the proportion of COs and other sentence outcomes in 2019. In 2021, around 17 per cent of sentencing outcomes for this offence were a CO. The implications of the findings in relation to non-custodial outcomes are discussed in the Possession offences overarching themes section, below.

For those offenders receiving an immediate custodial sentence for possession of a bladed article in a public place, the mean ACSL after any reductions for a guilty plea was 6.4 months in 2021, a reduction from 6.7 months in 2019, while the median ACSL has stayed consistent at 6 months’ custody since 2016 (Table 1). These trends are similar to those observed for all possession offences, which is not unexpected as this single offence comprises the majority of sentencing volumes for possession offences.

Table 1: Volumes and average custodial sentence lengths (ACSL) post guilty plea for offenders receiving immediate custody for possession of a bladed article in a public place, 2011 to 2021

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

N |

1,500 |

1,263 |

1,309 |

1,333 |

1,523 |

1,978 |

2,283 |

2,690 |

2,930 |

2,132 |

2,183 |

|

Mean |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.5 |

5.4 |

5.6 |

6.1 |

6.0 |

6.5 |

6.7 |

6.6 |

6.4 |

|

Median |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.7 |

3.3 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

Source: MoJ CPD

In relation to the application of the guideline, the lowest starting point in the guideline for most offences involving possession of a bladed article (culpability A) is 6 months’ custody, before any reduction for plea. Even after allowing for plea reductions, both the mean and median ACSL have been at or above this threshold since the Possession guideline has been in force. However, this has been the case since 2016, as opposed to appearing to be driven by the guideline itself. While the mean ACSL increased between 2017 and 2018, which could have been driven by the Possession guideline, it has since been falling slightly since 2019, and in 2021 the ACSL was 6.4 months.

Given the timing of this recent small decrease in mean ACSL and the decrease in proportion of immediate custodial outcomes, these changes are not thought to be related to the Possession guideline and are instead likely to be driven by the COVID-19 pandemic when court sitting times were drastically reduced and the imposition of immediate custodial sentences required additional considerations (see the Council’s note on the application of sentencing principles during the COVID-19 emergency). These issues impacted sentencing outcomes in 2020 and were still pertinent in 2021 as court backlogs grew.

Overall, the conclusion that can be drawn from the CPD sentencing data considered above for possession of a bladed article in a public place is that the evidence does not support the anticipated increase in prison resources of 80 additional prison places from the Possession guideline, as estimated in the resource assessment. While the proportion of non-custodial outcomes continued to decrease slightly post guideline, sentencing outcomes for possession of a bladed article in a public place were generally quite stable post guideline until around April-June 2020, after which changes have been observed which are unlikely to be the result of the Possession guideline but are instead likely to have been driven by COVID-19. The stabilisation of the median ACSL from 2016 onwards coincides with the introduction of the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody for a second or further relevant possession offence from July 2015 onwards. If sentencers were already following the principles prior to the introduction of the Possession guideline, this could explain why the expected prison place impacts were not seen. This is discussed further in the Possession offences overarching themes section, below.

Possession of an offensive weapon in a public place

The sentencing outcomes for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place follow a slightly different pattern to those for possession of a bladed article in a public place. Generally, the sentencing outcomes are slightly less severe, as might be expected from the way that weapons are referenced in the guideline, with bladed articles elevated to the highest culpability level in the guideline, alongside offensive weapons that are judged as ‘highly dangerous’. Other weapons fall into lower categories of culpability.

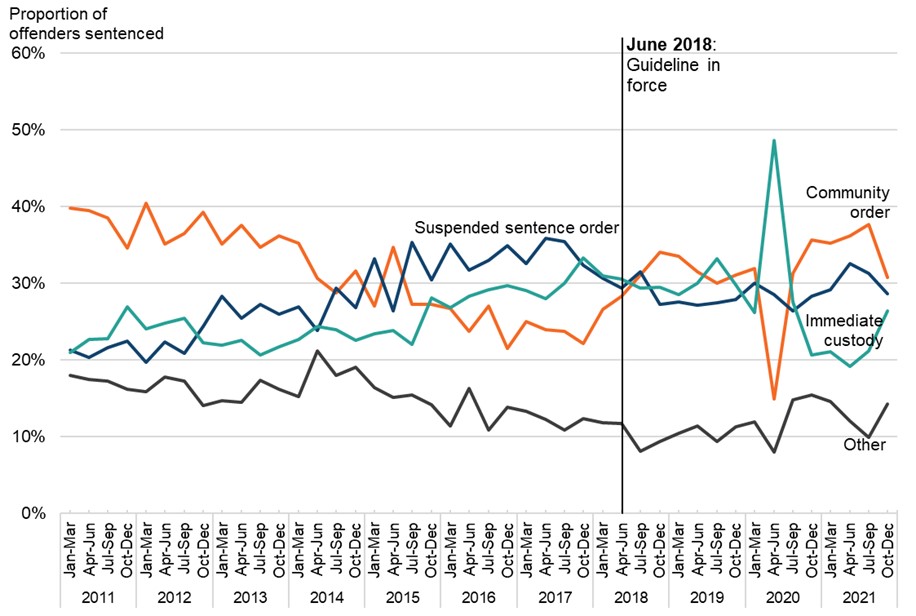

As seen in Figure 3, post guideline, the most frequent outcome for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place has generally been a community order (CO), with the exception of the period April-June 2020. In 2021, over one third (35 per cent) of adult offenders sentenced for this offence received a CO. The proportion of CO outcomes has generally increased since the end of 2017 onwards, when fewer than one quarter of offenders (22 per cent in October-December 2017) received a CO. Therefore, this increase appears to slightly predate the Possession guideline, so it is not clear if the guideline is the reason for this change.

Figure 3: Sentencing outcomes for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place, Jan-Mar 2011 to Oct-Dec 2021 (MoJ CPD)

As with possession of a bladed article in a public place, the proportion of offenders sentenced for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place receiving an immediate custodial sentence was increasing slightly before the guideline came into force, from around one fifth of outcomes in 2013 to around a third shortly before the guideline. This trend then appears reasonably stable until the spike in the middle of 2020, the timing of which coincides with the immediate impact of COVID-19, as observed for possession of a bladed article. However, contrary to the trend seen for possession of a bladed article, the proportion of suspended sentence orders (SSOs) for possession of an offensive weapon decreased from the end of 2017 and has appeared to stabilise from the end of 2018 onwards.

Table 2: Volumes and average custodial sentence lengths (ACSL) post guilty plea for offenders receiving immediate custody for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place, 2011 to 2021

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

N |

771 |

648 |

540 |

545 |

585 |

756 |

801 |

848 |

895 |

616 |

586 |

|

Mean |

6.8 |

7.2 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

7.4 |

6.4 |

6.7 |

7.0 |

6.9 |

6.7 |

6.2 |

|

Median |

4.7 |

5.6 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

Source: MoJ CPD

As seen in Table 2, for those offenders receiving immediate custody for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place, the median ACSL has been stable at 6 months’ custody since 2015, similar to possession of a bladed article. The implications of this shared finding are discussed more in the overarching themes section, below.

Pre guideline, the mean ACSL fluctuated a little more but generally the ACSL has remained similar pre to post guideline at slightly under 7 months’ custody, with the exception of 2021 which was a little lower. However, given the timing of this recent decrease, this is not thought to have been driven by the Possession guideline.

Overall, because of the impact of COVID-19, it is hard to identify what the lasting impact of the guideline might have been on sentencing for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place. However, there is no clear evidence of substantial changes around the time of the guideline coming into force.

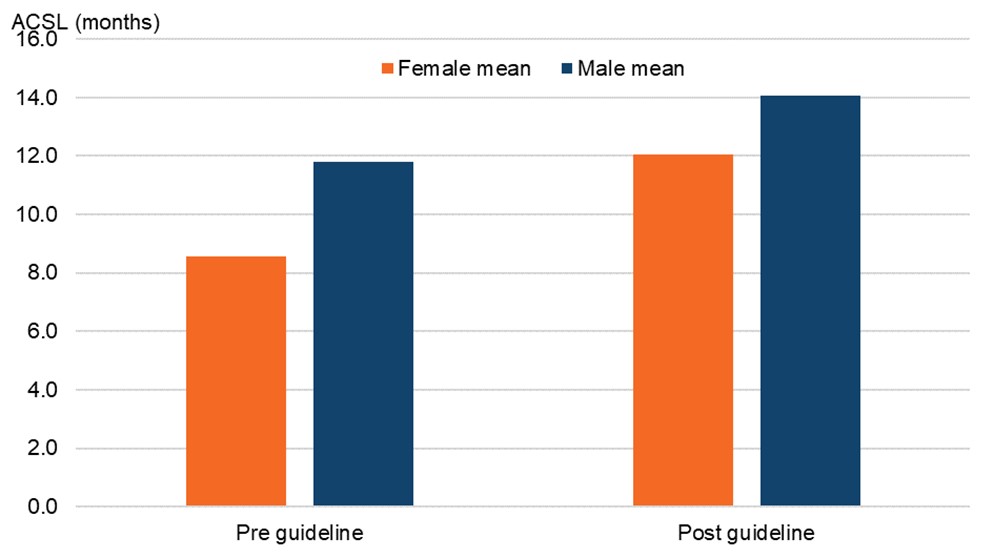

Demographic analysis

The available CPD data for possession offences regarding the sex, age, and ethnicity of the offenders being sentenced has been considered to examine if there are any differences in impact of the Possession guideline for offenders of different demographic groups.

Offenders sentenced for possession offences tend to be male (92 per cent pre and 93 per cent post guideline) and most frequently 30-39 years of age, although the general age profile is younger than that sentenced for other triable either way offences (16 per cent 18-20 years compared with 8 per cent, in 2021). No substantial differences in sentence outcome or ACSL were found when comparing the outcomes for males compared with females, or comparing between age groups for the period when the Possession guideline came into force.

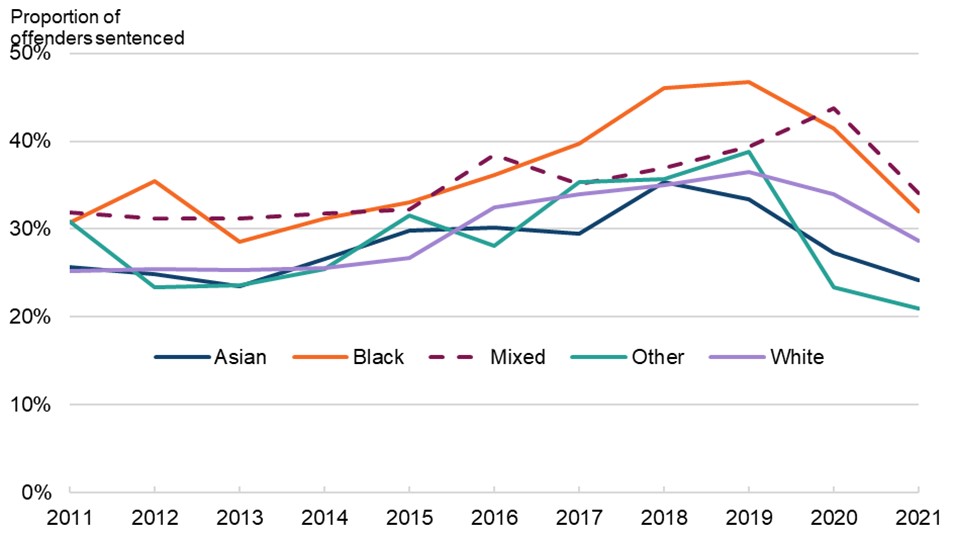

Regarding offender ethnicity, as seen in Figure 4, after 2017, black offenders became proportionately more likely to receive an immediate custodial sentence than offenders of all other ethnicities. For example, in 2018, 46 per cent of black offenders received immediate custody, compared with 35 per cent of white offenders. Given the guideline came into force during 2018, the data were examined on a more detailed quarterly basis to consider if it was possible that the Possession guideline may have contributed to any unwarranted disparities in sentencing for this demographic group of offenders.

Figure 4: Relative proportion of immediate custodial outcomes by self reported ethnicity for possession offences, 2011 to 2021 (MoJ CPD)

This trend analysis indicated that the increase in the proportion of immediate custodial outcomes for black offenders relative to white offenders started during 2017, and thus predated the Possession guideline coming into force. There were also no clear differences between ethnic groups in the ACSL for those offenders receiving an immediate custodial sentence for a possession offence.

3.1.2. Analysis of overarching issues

Overarching issue: Non-custodial outcomes

Analysis of CPD trend data

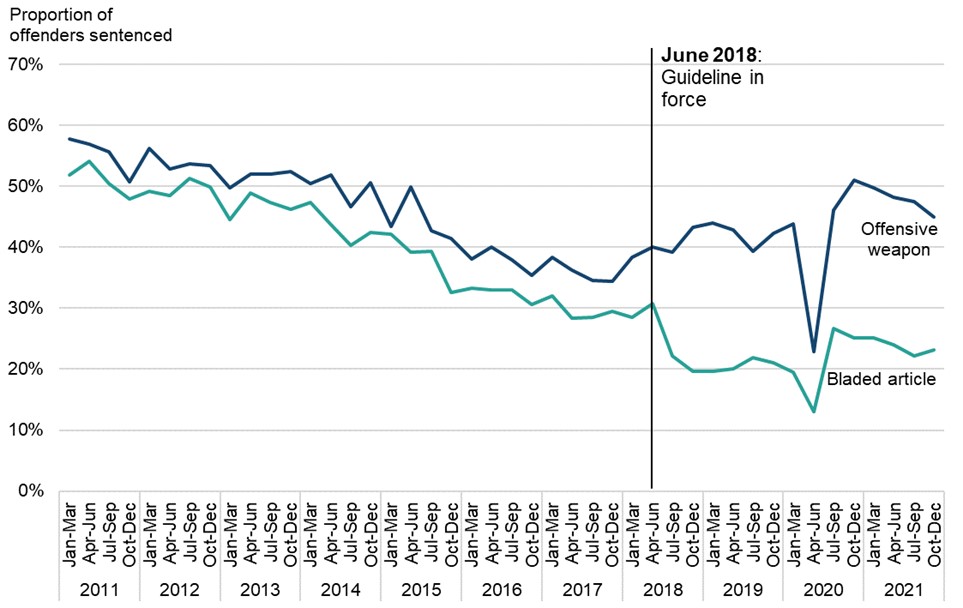

Given the expectation set out in the resource assessment that custodial outcomes would increase, and that the proportion of non-custodial sentences would therefore decrease, particularly for possession of bladed article offences, Figure 5 below compares the trend in the proportion of community order outcomes for possession of a bladed article in a public place against possession of an offensive weapon in a public place, on a quarterly basis.

As seen in the graph, and discussed previously, COs for these offences were generally decreasing before the guideline came into force in June 2018. However, we see some divergence in the trends from the end of 2017 onwards.

Figure 5: Proportion of community orders for possession of a bladed article or an offensive weapon in a public place, Jan-Mar 2011 to Oct-Dec 2021 (MoJ CPD)

For the offence of possession of an offensive weapon in a public place, COs increased in the months following the guideline coming into force, although this appears to have started pre-guideline, from October-December 2017. Sentencing for this offence then seems to be greatly affected by COVID-19 in the middle of 2020 when the proportion of COs fell sharply, then rose steeply to around half of offenders sentenced. For possession of a bladed article in a public place, although there is a rather steep decline immediately following the guideline coming into force, this does not persist. The proportion of COs for this offence appears less affected by COVID-19, with a much smaller inverted peak and recovery in the middle of 2020 compared with the possession of an offensive weapon offence. Across both offences, the proportion of COs appears to have started decreasing again in 2021.

In summary, the proportion of COs has not seen the decrease post-guideline that the resource assessment anticipated, at least not in the longer-term.

A potential explanation for this finding comes from the Imposition of community and custodial sentences guideline, which was published in February 2017. This guideline aimed to clarify the factors that may make it appropriate to impose a community order or to suspend a custodial sentence, if the case had truly passed the custody threshold. As seen in the Imposition guideline review, trend analysis suggested that the guideline was successful in clarifying these principles, as demonstrated by an increase in the proportion of community orders and associated decrease in the proportion of suspended sentence orders from around April 2018. It is possible that the Imposition guideline is the driver behind the plateau in CO outcomes after April-June 2018 for possession of a bladed article and the increase seen from 2017 onwards for possession of an offensive weapon.

Analysis of sentencing remarks

The CPD data alone cannot be used to understand the reason for an outcome being given. Instead, analysis of a sample of Crown Court judges’ sentencing remarks was conducted for the post guideline period to try to understand more about how the Possession guideline is being used in practice, and to explain the finding regarding the absence of a continued decrease in community order outcomes for possession offences (as shown in Figure 5). It should be noted that transcripts are only available at the Crown Court. As possession offences are sentenced mainly at magistrates’ courts, it is likely the cases covered in the transcripts will reflect the more severe end of sentencing. The findings were, therefore, used only to supplement and add context to the findings from the CPD analysis.

In total, a sample of 39 transcripts from cases sentenced post guideline from 2018 to 2021 (mostly from 2020) were analysed, containing the sentencing remarks for 40 offenders. The majority (22 offenders) concerned possession of a bladed article as the principal offence, 9 concerned the offence of unauthorised possession in prison of a knife or offensive weapon (although most of these involved knives or makeshift bladed articles), and in the remaining 9 the offender was charged with possession of an offensive weapon (although it should be noted that 4 of these cases involved a knife).

As expected, all of the 22 offenders in the post guideline sample sentenced for possession of a bladed article were categorised as culpability A by the judge, compared with only 5 of the 9 offensive weapon possession offences. Across both these offences, the majority of offenders were categorised as harm category 2. By contrast, all 9 of the unauthorised possession in prison offences were categorised as harm 1, as would be expected given the placement of the factor ‘Offence committed in prison’ within harm category 1.

Of the 27 offenders sentenced for possession of a bladed article or offensive weapon in a public place who were categorised in culpability A, while the starting point in the guideline is custody, around half (15 offenders) received immediate custody as their final sentence, a third (8 offenders) received a CO and the rest received an SSO. Within the sample that received a CO, the reasons provided by sentencers were explored, to see how they supported the possibility that the Imposition guideline might be able to explain the proportion of CO outcomes for possession offences. The reasons included a strong or realistic prospect of rehabilitation, personal mitigation or the mental health needs/vulnerabilities of the offender and reference to the interests of justice better being met with a CO.

These reasons overlap with the principles in the Imposition guideline for reducing a custodial sentence to a CO or suspending custody. Therefore, it is possible that sentencers are utilising the principles in this guideline to only impose immediate custody where it is unavoidable to do so when sentencing offenders for possession of a bladed article and offensive weapon. This could explain the rate of non-custodial outcomes for these offences, despite the guideline starting points.

Analysis of survey data

The magistrates’ court data collection undertaken for possession offences pre and post guideline is another source of evidence that can be used to examine the implementation of the Possession guideline and potentially further explain the findings in relation to the proportion of non-custodial outcomes observed in the trend analysis. It is possible to use this source to explore issues around the way sentencers approach applying the harm and culpability factors in the guideline to arrive at the final sentence, supplementing the evidence from sentencing remarks which are only available from the Crown Court.

Under the old guideline, offence seriousness was categorised into three levels, with level 1 the least serious and level 3 the most. At this top level, sentencers were directed to commit the case to the Crown Court for sentencing, as the guideline was for use in the magistrates’ courts only. Within level 1, the example provided for the nature of the activity was ‘Weapon not used to threaten or cause fear’, which corresponds with the wording of the culpability C factor in the new guideline.

As seen in Table 3, in around two thirds of the pre guideline data collection responses, sentencers judged the offence category to be level 1 (which has a starting point of a high level community order), indicating the weapon was not used to threaten or cause fear.

Table 3: Offence categorisations and frequency in pre guideline data collection

|

Offence level |

Guideline factor examples |

Starting point |

Range |

Proportion from data collection |

|

3 |

Weapon used to threaten or cause fear and offence committed in dangerous circumstances |

Crown Court |

Crown Court |

14% |

|

2 |

Weapon not used to threaten or cause fear, but offence committed in dangerous circumstances |

6 weeks’ custody |

High level community order – Crown Court |

18% |

|

1 |

Weapon not used to threaten or cause fear |

High level community order |

Band C fine – 12 weeks’ |

67% |

Source: Magistrates’ court sentencing survey.

By comparison, in the post guideline returns (Table 4), offenders most frequently fell into the A2 offence category, which has a starting point of 6 months’ custody. Culpability C was only recorded in 15 per cent of all post guideline returns, which is much less frequent than the comparable level 1 offence category in the pre guideline data. The majority of post-guideline returns falling into harm category 2 rather than 1 (83 per cent) aligns with the finding from the pre-guideline data regarding the weapons typically not being used to threaten or cause fear.

Table 4: Offence categorisations and frequency in post guideline data collection

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

|

1 |

11% |

4% |

2% |

[k] |

|

2 |

57% |

5% |

14% |

8% |

Source: Magistrates’ courts sentencing survey.

Note: Proportions calculated where harm and culpability known; one or both were missing from 13% survey responses. Percentage totals may not appear to sum correctly due to rounding.

[k] indicates that the proportion is less than 0.5%.

Given the CPD finding (Figure 5) that the proportion of COs has increased steadily since 2017 for offensive weapons offences and has also not decreased as much as anticipated for possession of bladed articles, the full data collection record for those cases receiving a community order were examined in detail. This allowed us to identify potential reasons as to why, despite a higher proportion of cases falling into a category post guideline with a custodial starting point, the proportion of custodial outcomes did not rise.

This analysis found that 92 per cent of the cases receiving a CO outcome had a guilty plea. Sentencers also frequently reported dropping down a threshold as a consequence of this guilty plea. This was more apparent for those cases involving possession of a bladed article (45 per cent of this subsample, compared with 27 per cent for possession of an offensive weapon), although this difference might be because the sentence was less likely to already be a CO before the application of the guilty plea for bladed articles. The outcome before guilty plea was unfortunately not recorded to be able to confirm this. Where the principal offence was possession of a bladed article, 74 per cent of cases receiving a CO also had the mitigating factor ‘No/minimal distress caused’ marked as relevant (which is notable because this factor does not appear in either the old or current guidelines) and in a third, the sentencer indicated that a culpability C or D factor was relevant. Half of those charged as possession of an offensive weapon receiving a CO had the culpability C factor ‘No threat or fear of violence’ ticked.

Furthermore, across all offences, it was found that sentencers tended to mark more mitigating factors than aggravating factors as relevant to their sentencing decision. In both pre and post guideline datasets, the most frequently cited factor in mitigation was ‘No/minimal distress caused’, ticked in over half (54 per cent) of post guideline cases and 42 per cent of pre guideline cases. The second most frequently recorded mitigating factor in the post guideline data was remorse (44 per cent). This is another factor which does not appear in either guideline (although it is acknowledged that the mitigating factors provided are not an exhaustive list of relevant factors, and remorse is a common factor in guidelines). Remorse was also commonly cited in the pre guideline data in around one quarter of responses.

Finally, in the data collection, sentencers were also asked to provide the ‘single most important factor’ influencing their sentencing outcome. This was completed in 94 per cent of post guideline returns so provides some useful additional context for the majority of cases in the data collection. These responses were thematically coded and, overall, one third of all responses contained a reference which could be interpreted as relating to offender mitigation, such as having no previous convictions or references to remorse, good character or the offender having caring responsibilities. By comparison, just one in six responses could be interpreted as relating to aggravation, such as the offender being on bail or being under the influence of alcohol or drugs. This backs up the finding from the data collection that sentencers may be placing a relatively high degree of weight on mitigation for sentencing these offences, compared with other offences for which this level of detail in the data has been analysed.

In conclusion, the higher weight given to mitigation compared to aggravation found throughout the data collection data, in combination with a high proportion of guilty pleas, could further explain why the proportion of CO outcomes was seen to plateau for bladed article offences shortly after the guideline came into force, rather than decrease further, as anticipated, and why there has also been no decrease in the proportion of CO outcomes for offensive weapons. It is acknowledged that the sample drawn on here relates to magistrates’ courts sentencing only, so will naturally be skewed towards cases of less severe offending. Nevertheless, this analysis complements the findings from the Crown Court sentencing remarks in relation to the application of Imposition principles, which is that a “custodial sentence must not be imposed unless the offence or the combination of the offence and one or more offences associated with it was so serious that neither a fine alone nor a community sentence can be justified for the offence”.

Overarching issue: Weapon categorisation

In addition to examining the type of outcomes received for these offences, it is important to explore other issues, to establish if sentencers are implementing the guideline as anticipated. One such overarching issue to consider is how sentencers are categorising the type of weapon involved in the offence.

In the old guideline, there was much less emphasis placed on the type of weapon within the offence categorisation. At step B, one of the listed factors indicating higher culpability was a particularly dangerous weapon, but this factor was only reported relevant in 5 per cent of pre guideline forms. Nevertheless, it has been important to consider the analysis post-guideline by the type of weapon that the possession offence relates to, given the rigidity of the guideline in relation to the placement of bladed articles and ‘highly dangerous’ offensive weapons.

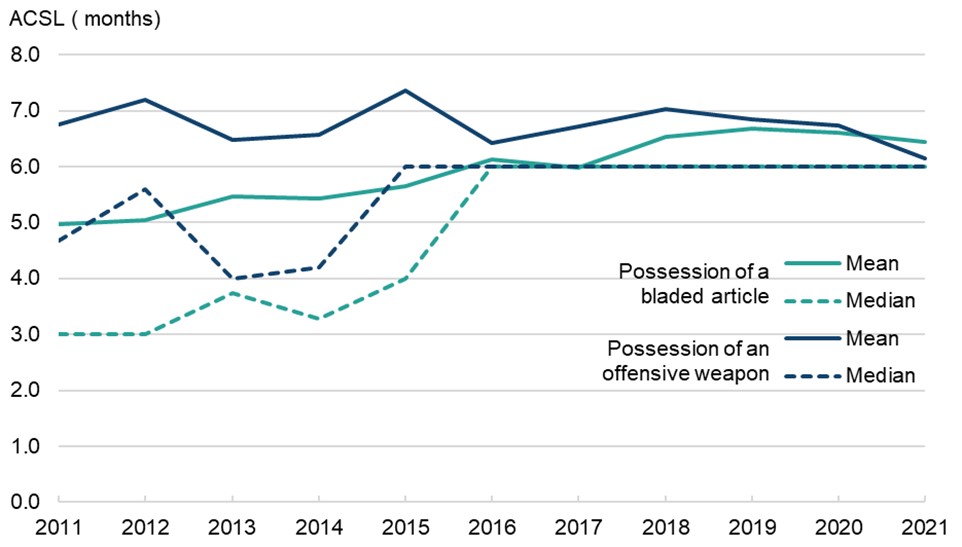

For those offenders receiving immediate custody for possession offences, Figure 6 compares the mean and median ACSL from the CPD data over time for bladed article and offensive weapons offences separately.

As seen in the graph, 2021 is the first year during the period analysed where the mean ACSL for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place was lower than for possession of a bladed article in a public place. Given the placement of the weapon factors in the Possession guideline, we might have expected this to have usually been the case prior to 2021. This finding might suggest that where offenders are receiving immediate custody for possession of an offensive weapon, this is because the offensive weapons involved are often judged to be ‘highly dangerous’, which is another culpability A factor.

Figure 6: Comparison of mean and median ACSL for possession of a bladed article and offensive weapon in a public place, 2011 to 2021 (MoJ CPD)

However, the small sample of Crown Court transcripts which were analysed presents another possible explanation, which is that cases of offenders charged with possession of an offensive weapon may also involve the possession of knives, which are then correctly categorised as culpability A. This was the case for 4 of the 9 cases in the sample.

The magistrates’ court survey data can also be used to explore this issue. In the pre guideline data collection, around two thirds of the 411 completed form returns were for possession of a bladed article in a public place, around one third were for possession of an offensive weapon in a public place (fewer than five forms were received in total for the remaining three possession offences). Similar proportions were also seen in the post guideline collection, where 63 per cent of the 928 returned completed forms involved sentencing an offender where possession of a bladed article in a public place was the principal offence. These distributions follow the pattern seen in the CPD data.

Generally speaking, the offence categorisations supported the expectation that possession of a bladed article is categorised more severely than possession of an offensive weapon. However, post guideline, 42 per cent of offenders sentenced for possession of an offensive weapon were placed in culpability category A by the sentencer overall and almost half (49 per cent) had at least one culpability A factor ticked. It was initially thought that these would therefore be cases involving a highly dangerous weapon.

Further investigation of the data revealed that over 80 per cent of all the survey returns where possession of an offensive weapon was selected as the principal offence and the offender’s culpability was categorised as A overall had the factor ‘Possession of a bladed article’ ticked, and this factor was ticked in 40 per cent of all survey returns for this offence. This echoes the finding from transcript analysis that some cases charged as possession of an offensive weapon may involve a bladed article.

Additionally, across all possession offences, post guideline, examples of the weapons in offences that involved ‘Possession of a highly dangerous weapon’ include a kitchen knife, an axe and a machete, which reinforces the idea that highly dangerous and offensive weapons often tend to also be bladed articles.

It is not known why these cases were charged as possession of an offensive weapon instead of possession of a bladed article, but this finding may also explain why the ACSL in the CPD data for possession of an offensive weapon was not typically much lower than for possession of a bladed article. It suggests that caution should be taken in interpreting differences between these offences at a principal offence level only.

Given that the data collection collected detail on the type of weapon involved, this can be used instead of the principal offence to explore whether sentencers are sentencing the weapons involved in possession offences as expected, irrespective of the offence being charged. In the pre guideline collection, the most frequent weapon category was a kitchen knife, reported in around one third (34 per cent) of the survey returns. Where this weapon was involved, the majority (58 per cent) were categorised into level 1 (weapon not used to threaten or cause fear).

In the post guideline data, the majority of the weapons involved were again either a kitchen knife (32 per cent of responses) or a lock knife (24 per cent). All weapons (including those recorded in free text responses) in the post-guideline data collection were coded as to whether they were a knife or a bladed article, as per the definition set out in legislation (see the Overarching Issues section at the beginning of this report for more details). Where this was the case, the overall culpability category was A in the majority (81 per cent) of the survey returns, as would be expected when following the guideline. Given that ‘Possession of a bladed article’ is the first factor within culpability A, this suggests that sentencers may have had other reasons for not placing the remaining 19 per cent of offenders in culpability A.

This subsample of 128 cases where the overall culpability category was not recorded as A, even though the weapon involved was a knife or bladed article, were analysed. In around one third (46 cases, 5 per cent of total survey returns) the sentencer indicated that the culpability D factor ‘Possession of weapon falls just short of reasonable excuse’ was relevant to their sentencing decision; the overall culpability category selected was D in all but two of these cases, which was not the intention of the inclusion of this factor. In the scenario described, the intention of culpability D was to enable some knife or bladed article cases to be assigned a lower culpability category in the situation where the reason for the possession of the weapon fell just short of the defence of reasonable excuse. It was intended that a sentencer would balance the factors A and D, resulting in culpability B or C overall.

There were also a further 79 responses, representing 9 per cent of total survey returns, where the weapon involved was coded as a knife or bladed article and this culpability D factor was not marked as relevant, but the overall culpability category was recorded as B or C. Again, this was not the way the guideline was intended to be used.

However, it should be noted that the final outcome was either custody or a Crown Court committal in 54 of the 126 cases (43 per cent) where the culpability categorisation was not as expected in relation to the weapon involved.

Overarching issue: Statutory minimum sentence

Another overarching issue to explore in relation to implementation of the Possession guideline is application of the statutory minimum sentence, outlined at step 3 of the guideline. The CPD data cannot be used to explore this for possession offences as the data record does not contain the relevant detail about the offender’s previous convictions. Nevertheless, in relation to Figure 6 above, the stabilisation of the ACSL for possession offences from 2016 onwards, rather than directly following the Possession guideline, is an interesting finding as the timing of this coincides with the introduction of the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody for a second or further relevant possession offence from July 2015 onwards. Given that the guideline sought to simplify and reinforce the principles for sentencing these offences, the lack of a substantial change in ACSL from the date of the guideline could suggest that sentencers were already mostly following these principles prior to the guideline coming into force.

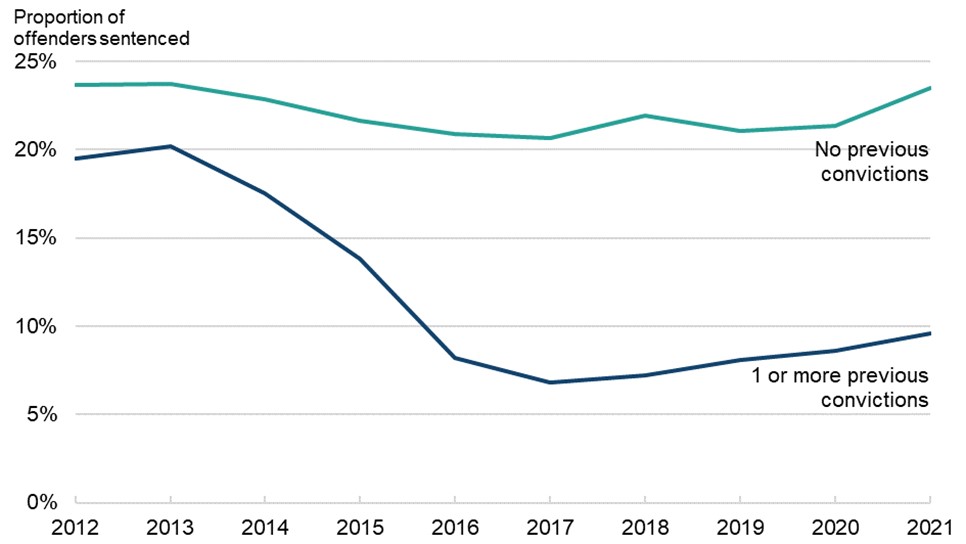

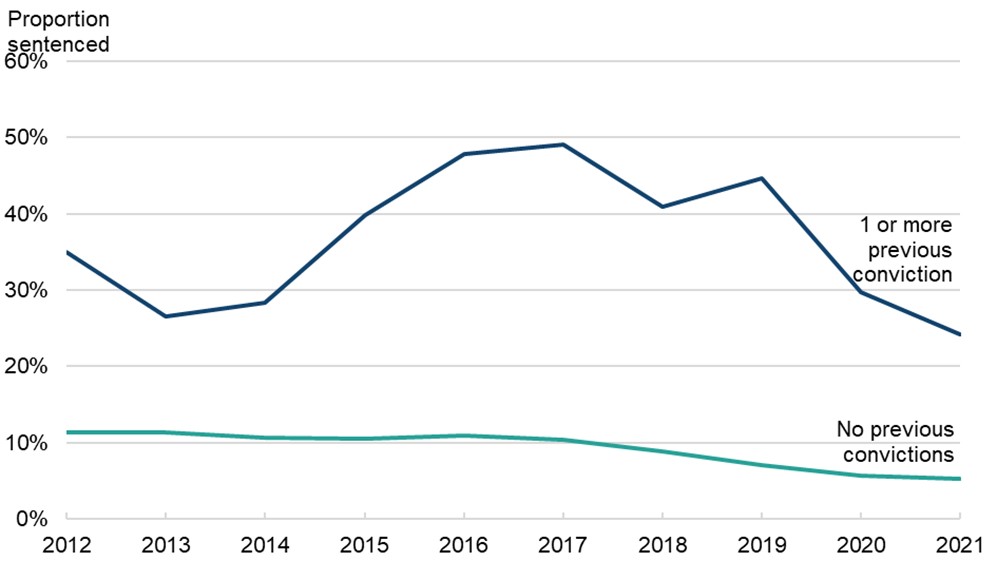

Other evidence to support the successful implementation of the statutory minimum sentence within the Possession guideline comes from the MoJ’s Knife and offensive weapon sentencing statistics publication. The data are produced using the Police National Computer and will be on a different counting basis to the CPD figures, so caution should be exercised when comparing between the two sources.

Data from this publication indicate that around one third of offenders sentenced for a knife possession offence had at least one or more previous convictions or cautions for a qualifying offence (any previous knife and offensive weapons offences). The proportion of adult offenders receiving a community sentence for a possession offence where the offender had no qualifying previous convictions or cautions has stayed mostly stable over the past decade. However, for those offenders with one or more qualifying previous convictions or cautions, so including those for whom the legislation indicates they should be receiving a custodial sentence, the frequency of community sentence outcomes is much lower – fewer than 10 per cent in 2021. As seen in Figure 7, this proportion fell sharply from 2013 but this decline stopped after 2017, with only a slight increase from 2017 to 2021. This echoes the stabilisation of the mean and median ACSL seen in the CPD data from 2016 onwards (Figure 6).

Figure 7: Proportion of adult offenders who received a community sentence, by number of previous knife offence convictions, 2012 to 2021 (Source: MoJ Knife and Offensive Weapon Statistics)

This data suggests that the introduction of the guideline in 2018 has preserved the decline that took place prior to its introduction, and ensured a consistently low level of community sentences are being imposed on offenders with qualifying previous convictions. This evidence also provides further support for the conclusion that sentencers were already following many of the principles in the Possession guideline prior to its introduction, and this is why the anticipated resource impacts were not observed.

This is also supported by a content analysis of sentencing transcripts. For 15 of the 40 offenders in the sample, the sentencer mentioned that the offence being sentenced was their second or further relevant offence, which aligns with the 30 per cent observed in the MoJ Knife and offensive weapon sentencing statistics. The sentencer considered it unjust to impose the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody in 2 of these cases, imposing a community order instead. In a further 2 cases, the period of custody was suspended. In all cases where applicable, the sentencer acknowledged the exceptional circumstances of the case and considered this to be the best course of action to address the offending behaviour and reduce the risk of reoffending.

In relation to the reasons provided by the sentencers not to impose the statutory minimum sentence, these align with those in the guideline to justify the circumstances in which a sentencer could consider it unjust. This provides evidence that sentencers are implementing the Possession guideline as intended, particularly with regard to the statutory minimum sentence for these offences.

Regarding survey data on this issue, one of the questions asked sentencers to indicate whether the offence being sentenced was a second or further relevant offence, (and hence subject to the statutory minimum term of 6 months’ custody). If the sentencer selected yes, they were asked whether there were any circumstances that meant imposing this minimum term would be unjust, aligning with the reasons set out in the guideline at the point of analysis (see the Overarching Issues section above for more details).

For the pre guideline collection, sentencers were asked to record whether the reason for not imposing the minimum sentence related to the offence, the offender, or both. However, in the post guideline collection, sentencers were given a free-text box to record their reason, which has then been coded into these same categories, as well as some additional detail which is shown in Table 5. Sentencers could list multiple reasons, so the percentages do not sum to 100.

Across both possession of a bladed article and offensive weapon, in 28 per cent of the pre guideline responses and 25 per cent of the post guideline responses the sentencer indicated that the offence being sentenced was the second or further relevant offence for that offender. These proportions are generally in line with evidence from the MoJ Knife and offensive weapon offences statistics publication and content analysis of sentencing remarks at the Crown Court discussed earlier. The sentencer then went on to indicate that they believed imposing this minimum term would be unjust in all the circumstances in 26 per cent of pre and 20 per cent of post guideline instances, totalling 29 responses pre guideline and 46 responses post guideline.

Volumes are still low across both collections, which limits the robustness of any conclusions. Nevertheless, pre guideline, the circumstances of the offender were the most commonly referenced reason, cited slightly under half the time (45 per cent). Sentencers indicated that the circumstances of both the offence and the offender influenced their decision 41 per cent of the time, whereas the offence alone was only cited for 14 per cent.

Table 5: Reasons given by sentencers to support their decision not to impose the statutory minimum sentence, post guideline.

|

What reason relates to |

The reason given for statutory minimum being unjust in all the circumstances |

Proportion of cases mentioned |

|

Offence |

Seriousness/circumstances of the offence |

33% |

|

Offence |

Period of time elapsed since previous offence |

52% |

|

Offender |

Strong personal mitigation |

22% |

|

Offender |

Realistic prospect of rehabilitation |

26% |

|

Offender |

Significant impact of custody on others |

2% |

Source: Magistrates’ courts sentencing survey.

Post guideline, the circumstances of the offence were more frequently referenced; over half of sentencers cited the duration of time that had elapsed since the previous offence as their reason for not imposing the minimum sentence and a third mentioned the seriousness/circumstances of the offence. Of the small sample where ‘strong personal mitigation’ was cited as one of the reasons (10 cases), 7 referenced the mental health of the offender as a relevant mitigating factor.

These reasons may provide further evidence to explain why the proportion of non-custodial outcomes did not decrease substantially as expected, after the Possession guideline came into force.

Of the remaining cases where the sentencer did not indicate that it would be unjust to impose the minimum sentence, a final sentence was lower than expected in fewer than five per cent of occasions in both the pre and post guideline data. Furthermore, for all cases where the sentencer flagged that the offence was a second offence, only 2 per cent of both the pre and post guideline final outcomes were below the expected threshold.

This provides further evidence to support the successful implementation of the Possession guideline in relation to the application of the statutory minimum sentence for a second or further relevant knife offence. It could also explain why there was no substantial change in ACSL when the guideline came into force, as was expected.

Overarching issue: Appeals against sentence

One final area to explore in relation to implementation relates to appeals against sentence. If there were any particular implementation issues with the guidelines, we might expect to see some of these arise on appeal. To examine this, 19 transcripts of Court of Appeal judgments for cases originally sentenced for either possession alone or for possession alongside a threat offence, from July 2018 onwards, were analysed. This sample represented around half of the 40 appeals against sentence for these offences (i.e. not including sentencing for a threat offence alone) which have taken place post-guideline.

Of the sample of 19 transcripts analysed, 7 were dismissed and 12 were allowed, although only 5 of those which were allowed were done so in relation to the application of the relevant bladed article guideline originally – the others concerned the application of the principle of totality or the guilty plea reduction. The majority were appeals against the sentence for the offence of possession of a bladed article or offensive weapon alone (17 appeals) and two transcripts involved both a possession and a threat offence.

Within the subsample of appeals that were allowed, and the original application of the guideline was referenced as the reason for this (5 cases), all the appeal decisions ultimately agreed with the harm and culpability categorisations of the sentencing judge. Where they deviated was in the application of the appropriate starting point and any aggravating and mitigating factors. In several instances, the sentencing judge moved beyond the offence range within the guideline, but on appeal this was deemed to be manifestly excessive. In another judgment the appeal judges disagreed with the conclusion that a term of immediate imprisonment could not be avoided and instead ruled that the sentence should be suspended based on the strong mitigating circumstances.

This supports earlier findings in this report regarding the high weight seeming to be placed on mitigation by sentencers for these offences, which are often used to justify suspending the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody.

3.2. Threat offences

Summary of findings

- The majority of offenders received a custodial sentence for threat offences, of which around one quarter were suspended, in the years immediately post-guideline. This represents a stabilisation of the pre-existing trend.

- For offenders receiving immediate custody, almost all sentences were above the statutory minimum sentence of 6 months’ custody.

- The ACSL for offenders receiving an immediate custodial sentence increased pre to post guideline by 2 months. It is not known if these increases would have persisted; sentencing trends in 2020 and 2021 have been impacted by COVID-19.

- Very few offenders receive a non-custodial outcome for these offences. A realistic prospect of rehabilitation was the most frequent reason sentencers were found to give for not imposing the statutory minimum sentence.

3.2.1. Summary trend analysis

All threat offences

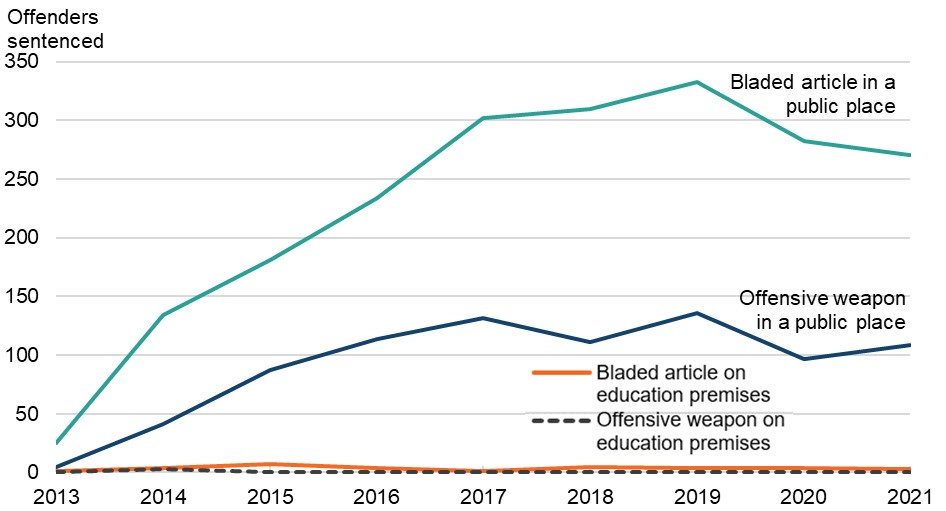

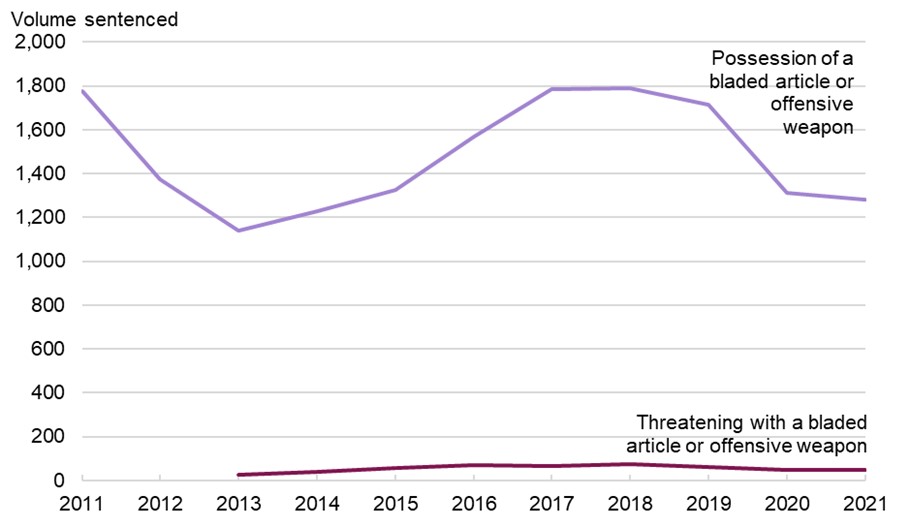

Offences of threatening with a bladed article or with an offensive weapon were introduced in December 2012 and so CPD data only exists from 2013 onwards.

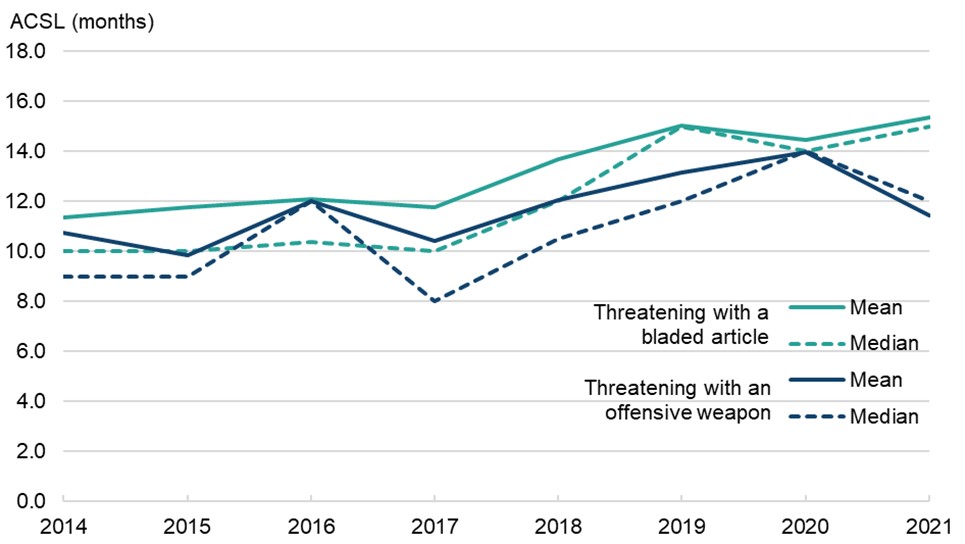

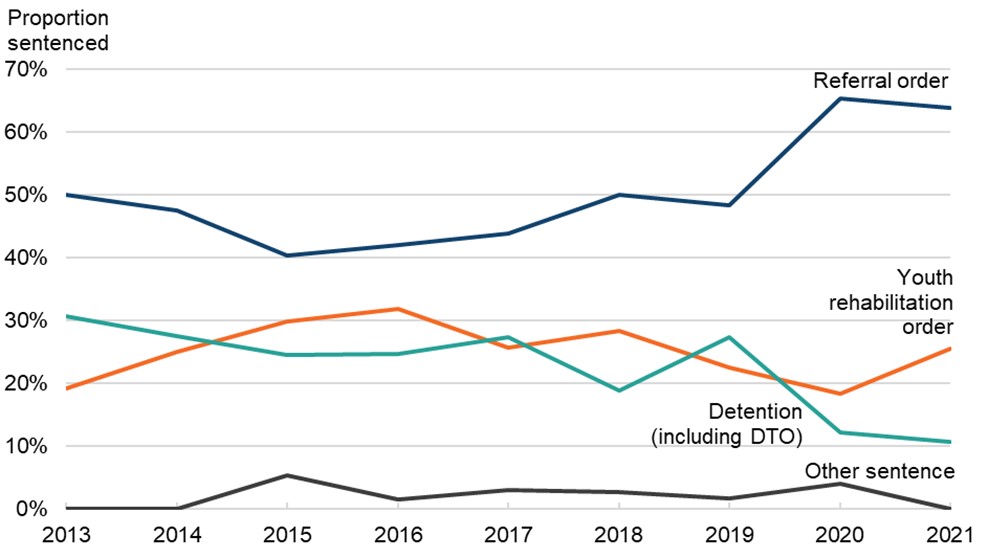

The three threat offences covered by the Threats guideline are relatively low volume compared with possession offences. In 2021, around 380 offenders were sentenced for threat offences, of which over two thirds (71 per cent) were for threatening with a bladed article in a public place. Fewer than five offenders were sentenced for threatening with an article with a blade/point or with an offensive weapon on education premises (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Volume of adult offenders sentenced all threat offences, 2013 to 2021 (MoJ CPD)

Analysis of the CPD data shows that volumes for threatening with a bladed article or an offensive weapon in a public place generally rose sharply until 2017, but this increase has slowed in recent years. It is likely that volumes over the last two years have been impacted by COVID-19, so volumes may increase again in the future. The vast majority of offenders are sentenced at the Crown Court for threat offences, which has not substantially changed with the existence of the Threats guideline – in 2017, around 86 per cent of adult offenders were sentenced at the Crown Court and in 2021 this figure was 90 per cent.