James Thornton, Sophie Gallop, Loretta Trickett, Orla Slattery, Kirsty Welsh, Jonathan Doak

Nottingham Law School, Nottingham Trent University

1. Summary

1.1 Background

In 2006, the Sentencing Guidelines Council (SGC) published a definitive guideline Overarching principles: domestic violence. In 2018, the Council revised the guideline to reflect important changes in terminology, expert thinking and societal attitudes in this important area of sentencing. To reflect the fact that both physical violence and controlling behaviour can constitute domestic abuse, the title of the guideline was changed to Overarching principles: domestic abuse. The guideline was updated in 2021 to reflect the enactment of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, including that Act’s statutory definition of domestic abuse.

Towards the end of 2023, the Sentencing Council commissioned Nottingham Trent University (NTU) to conduct a review of the guideline. The review focused on how the guideline is used in sentencing as well as sentencers’ understanding, interpretation, implementation, application, and thoughts about the current guideline. It also explored the impact of the presence of domestic abuse on the sentence.

1.2 Methodology

The review was conducted using a mixed method approach, which consisted of the following:

Primary data

- An online anonymous survey of 358 sentencers (53 judges and 305 magistrates) exploring sentencers’ use and thoughts about the guideline. The questions included in the survey can be seen at Annex A.

- Forty semi-structured qualitative interviews with sentencers (20 from the Crown Court and 20 from magistrates’ courts). Interviews were designed to allow for more in-depth discussion than the survey and to allow for interviewees’ points to be elaborated upon and clarified in response to interviewer probing. Interviews included sentencers reviewing hypothetical scenarios which can be seen at Annex B.

Secondary data

- Analysis of 413 transcripts of Crown Court sentencing remarks covering 19 offences across the broad areas of assault, kidnap and false imprisonment, harassment and stalking. Each transcript was reviewed for the presence of potential domestic abuse or context by reference to the domestic abuse guideline’s definition. Transcripts were coded thematically.

- A systematic review of all published sentencing appeal judgments using search terms related to the overarching guideline and domestic abuse. The search terms can be found under section 3.2.2 of this report. Searches returned 42 relevant appeal judgments between the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline in 2018 and early 2024. Judgments were analysed thematically.

- Analysis of a relevant sample of past Sentencing Council data from court data collections. The offences analysed included assault, harassment, criminal damage, and breach of a protective order. Analysis focused on the answers to the questions about whether domestic context was relevant to the case and, if so, its impact on the sentence.

1.3 Limitations

Across the data sources outlined above, the following limitations should be borne in mind when considering how representative or conclusive the findings are:

- The data can only be said to be indicative of the views/practice of the sample of sentencers covered through the different data strands. Due to sample sizes, they cannot be said to be statistically representative of the sentencer population

- As the survey and interviews relied upon participants volunteering, there is a risk of self-selection bias. This can mean that while participants are readily engaged with this area of research, such respondents may be differently inclined in terms of sentencing practice, their use of the domestic abuse guideline and so on than the general cohort of sentencers

- Sentencing transcripts are only available from the Crown Court and Court of Appeal; evidence is therefore limited to what was said in those courts

- It is difficult to conclude that any differences in the application of the domestic abuse guideline (as identified using the data collected in past court data collections) were due to the overarching guideline itself. There are a large number of variables that could have influenced the changes

- Some cases may not be fully recorded (or recorded at all) in data collection exercises, due to human input errors or lack of time on the day.

1.4 Findings

1.4.1 When and how sentencers use the domestic abuse guideline

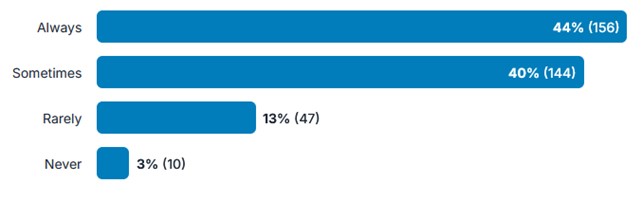

- Forty-four per cent of the survey respondents said they ‘always’ refer to the domestic abuse guideline when sentencing cases of domestic abuse, 40 per cent ‘sometimes’, 13 per cent ‘rarely’, and three per cent ‘never’. In interview, some of those who used it considered that it was a useful reminder of key principles and was a useful training aid for new sentencers. Others used it more extensively, for detailed application in the sentencing process. For example, for assessing ‘harm’ and ‘culpability’ under the relevant offence specific guideline, stating that the domestic abuse guideline applies and therefore there is an additional aggravating factor, or in considering in detail the guideline’s aggravating and mitigating factors. The most common way that sentencers used the domestic abuse guideline was to refer to its list of aggravating factors “of particular relevance to offences committed in a domestic context”.

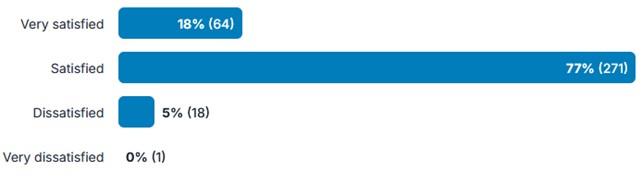

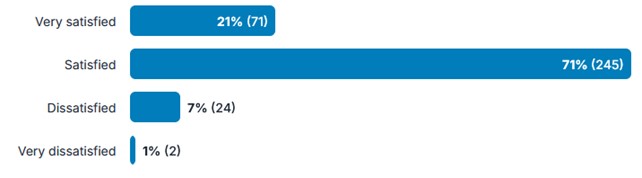

- There was generally a high level of satisfaction with how usable the guideline is in practice. Ninety-five per cent of survey respondents were at least ‘satisfied’ with the guideline’s layout, structure or ease of use.

- Within analysis of the aforementioned sentencing appeal judgments, the case of R v Baldwin [2021] EWCA Crim 417, noted that greater engagement with the domestic abuse guideline rather than just treating the domestic context as an aggravating factor is required.

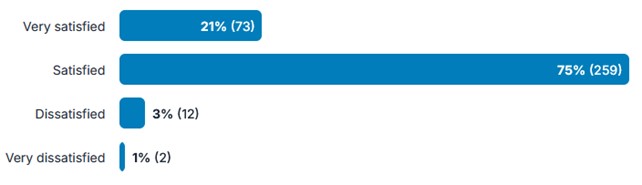

- While 87 per cent of survey respondents said they found the domestic abuse guideline helpful in sentencing, 13 per cent did not. For the most part, those with positive views thought that the guideline was a helpful document, with relevant and useful information, for example of things to take into consideration in sentencing cases involving domestic abuse, as a source of general guidance to assist identifying domestic abuse, and as a checklist.

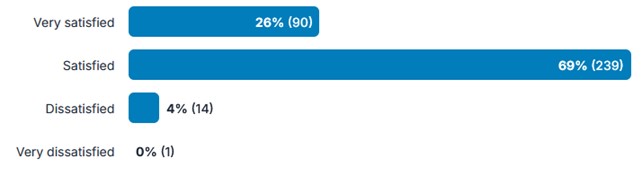

- Reasons provided in the interviews and survey for not using the guideline included it just being “common sense”, “obvious” or prioritising offence specific guidelines (among other documents) in busy courts. This echoed findings of the User testing survey analysis – how do guideline users use and interact with the Sentencing Council’s website? published in November 2023 in which sentencers shared that, due to a sense of familiarity with the overarching guidelines and their principles, they did not feel the need to refer to the domestic abuse guideline in each case in which the guideline was relevant.

- The sentencing transcripts reviewed were noted to have included a number of instances in which the domestic abuse guideline was not specifically mentioned in the remarks, despite the guideline being particularly relevant to the cases. However, it is possible that the sentencers had referred to or applied the principles of the guideline but did not formally mention it in their remarks. They could also have applied factors or principles related to domestic abuse that appear in offence specific guidelines such as ‘Offence committed in a domestic context’.

1.4.2 The impact of the domestic abuse guideline on sentences

- The Council’s past data collection exercises provided a mixed picture in terms of the domestic abuse guideline’s potential influence on final sentence outcomes where cases had been identified as having been committed in a domestic context. There were three offences for which the collections pre- and post- the offence specific guideline were also before and after the revision of the domestic abuse guideline: harassment, breach of protective order and criminal damage.

- For harassment, there was an increase in the proportion of cases having their sentence increased in some way to reflect the domestic context following the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline. After the introduction of the guideline 70 per cent had their sentence increased, compared to 45 per cent prior to the guideline’s introduction.

- For breach of a protective order, a slight increase in the sentence was observed. The domestic context was reported to have increased the sentence in 50 per cent of cases following the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline, compared to 43 per cent of cases before the guideline came into force.

- For criminal damage, little difference was recorded pre- and post- the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline. Following the introduction of the guideline, the domestic context was said to have increased the sentence in 35 per cent of cases compared to 39 per cent of cases prior to the guideline’s introduction.

- Interviewees reported that the presence of domestic abuse played a part in deciding whether or not to suspend a custodial sentence. Often, this was used as something operating in favour of imposing immediate custody.

1.4.3 Sentencers’ views on when the domestic abuse guideline applies and what constitutes ‘the domestic context’

- In the survey and interviews, some sentencers reported relying on “common sense” to decide whether an offence was committed in a domestic context and referred to the type of relationship and/or the location of the offence as the reason for classifying a case as involving domestic abuse. Sentencers predominantly focussed on the relationship between the parties as a way to classify whether a case was in a domestic context. This was primarily observed in interviews during discussion of scenarios, which included heterosexual relationships. Despite this, sentencers also gave other examples of relationships including, same-sex co-habiting couples, extended family members, or adult children and parents (this aligns with paragraph two of the domestic abuse guideline). Across the sample of sentencers, judges were more likely than magistrates to turn to and use the domestic abuse guideline in order to decide whether the offence had been committed in a domestic context. In interview, some magistrates pointed out a lack of guidance on relationship length.

- In relation to location, sentencers’ main focus in interview was on family or separated couples’ homes (for example where contact between the two took place incidentally, due to contact arrangements around children). However, some also mentioned shared accommodation, such as houses of multiple occupancy (HMOs). Some felt that it was not just the location of the offence itself that put a case in a domestic context, but a degree of dependency and trust between the victim and offender was also required. Others felt that a more intimate or familial relationship is required to fulfil the classification.

- In accordance with case law, others in interview considered the offender’s conduct when deciding whether an offence was in a domestic context, such as: violence, coercion, control, and attempts to undermine and humiliate the victim. Where sentencers analysed this aspect, they would often make use of the behavioural factors indicated in the domestic abuse guideline, as indicative of domestic abuse. A few sentencers commented on use of technology to control, noting that the domestic abuse guideline could provide further information as to the operation of this kind of abuse.

- Some ‘grey areas’ and inconsistencies as to what counts as ‘domestic context’ were identified, such as:

- houses in multiple occupation (HMOs)

- longstanding platonic relationships of trust/dependence

- stalkers (delusionally) believing they are in a romantic ‘relationship’ with the victim, providing a similar sense of entitlement/power to that of domestic abusers

- death occurring as a result of neglect

- mercy killings

- cases of modern slavery

- instances where there are multiple defendants, and one is abusing the other

- where a long-term victim of domestic abuse ‘snaps’ and attacks or kills their abusive partner

- where a victim of domestic abuse commits offences against others as a result of their abuse

It was implied that further guidance in these areas may be beneficial.

- In interview, a ‘virtual/online space’ was a location that appeared to be more problematic for sentencers in deciding whether the offence was committed in a domestic context. It was suggested that the applicability of the space could be clarified within the guideline. This could be particularly relevant in the context of the proliferation of social media and other technologies, which can allow enhanced monitoring, control and harassment of individuals.

1.4.4 Practical issues

- There was generally a very high level of satisfaction in the survey in terms of how the domestic abuse guideline works in practice. Ninety-five per cent of survey respondents were at least ‘satisfied’ with its ‘layout, structure or ease of use’. Conversely, some sentencers raised concerns regarding utility in a busy court: where they are already looking at numerous other guidelines and documents, some found it difficult to locate the guideline when busy or under time constraints. Some suggestions were made to add a link to the guideline at the top of each offence specific guideline, as well as greater use of bullet points, tables, checklists and the highlighting of key words (e.g., provocation, children, and restraining order) to help find the guideline’s information on these issues more quickly.

- It was suggested in the survey and interviews that there was insufficient interaction with and cross-referencing from offence specific and other overarching guidelines. Sentencers are directed to the domestic abuse guideline via a drop down under the aggravating factor ‘Offence committed in a domestic context’; however, this link is somewhat buried. It is therefore suggested that this could be made more prominent within offence specific guidelines and a brief explanation added. However, some interviewees found the non-prescriptive nature of the guideline to be an advantage.

- Sentencers noted that they would like to see a formal uplift in the domestic abuse guideline, similar to guidance contained in offence specific guidelines on the uplifts in sentences for hate crimes and assaults on emergency workers. It was suggested that this could be referenced in the domestic abuse guideline as well as relevant offence specific guidelines.

1.4.5 Other specific issues

- Some comments in response to the survey noted that the guideline did not provide much assistance in terms of the imposition of restraining orders where child contact is raised as an issue. It was suggested that some guidance on the particular wording or provisions to consider in these cases might assist. Similar concerns were raised in relation to the length of these orders. Considerations in the drafting of these orders have been reflected in case law such as R v Khellaf [2016] EWCA Crim 1297. It may be of assistance to sentencers to have this reflected in the guideline.

- The domestic abuse guideline encourages sentencers to consider potential rehabilitation programmes (paragraph 17). However, issues with a lack of availability of some of the relevant probation courses and the unsuitability of offenders with certain characteristics for some courses e.g., when they are only for males, may suggest a problem with the assumptions that the guideline is based on. Sentencers thought it was unclear what to do if the courses are unavailable or unsuitable.

- Many survey respondents and interviewees felt that the domestic abuse guideline needed to be updated, at the very least to take account of the new non-fatal strangulation offence and the consequent seriousness with which such conduct is now treated. Some suggested this should be added to the list of aggravating factors “of particular relevance to offences committed in a domestic context”, and/or in the ‘Scope’ and ‘Assessing seriousness’ sections of the domestic abuse guideline. A suggestion was also raised to include in the guideline things to look out for that could be indicative of future risk, such as strangulation, stalking, and threats to kill.

- It was mentioned by respondents and interviewees that sentencers are expected to order compensation in cases of domestic abuse. However, comments suggest that the approach in domestic abuse cases is to assume that it will do more harm than good unless and until the victim of the offence informs the court. If this is regarded as the correct approach by the Council, sentencers could benefit from this being outlined in the domestic abuse guideline.

- The application of the mitigating factor of provocation within the Council’s data collection exercises was explored, which found that the recording of this factor was rare. It was therefore suggested that the domestic abuse guideline could elaborate on the “rare circumstances” where provocation may be relevant, particularly cases where victims of abuse lash out at their abuser.

- Where there are multiple defendants and one is abusing the other, it was also suggested that the guideline might also cross-reference the ‘Difficult and deprived background or personal circumstances’ factor which was recently introduced by the Council. The factor also includes ‘Direct or indirect victim of domestic abuse’; however, this wording appears at the bottom of a list of 12 other sub-bullet points in the majority of offence specific guidelines. To incorporate this reference into the guideline may enhance its prominence.

- The relevance of a previous record or pattern of abusive behaviour without convictions lacks clarity. Some sentencers seemed prepared to consider things like previous non-molestation orders, harassment warnings and the like to be separate aggravating features for domestic abuse offenders (as demonstrating a pattern of behaviour or that the offender ought to have known better, having already been given a chance or warning), but others did not.

- Sentencers noted that the mitigating factor ‘Good character’ may have little relevance and therefore exercised caution in relation to the factor in interview. They did note that the guideline’s comments on this assisted them with avoiding taking good character at face value. It should be noted that the wording of this factor was changed to include positive good character, rather than solely good character in April 2024.

2. Introduction

2.1 The Sentencing Council and sentencing guidelines

The Sentencing Council for England and Wales was established in April 2010 (under s118, of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009) in order to promote greater transparency and consistency in sentencing, while maintaining the independence of the judiciary.

The Council is an independent, non-departmental public body which is part of the Ministry of Justice’s family of arm’s-length bodies. The Council has statutory duties to:

- develop and issue sentencing guidelines and monitor their use

- assess the impact of guidelines on sentencing practice

- promote awareness among the public regarding the realities of sentencing, and publish information about sentencing practice in magistrates’ courts and the Crown Court

The majority of sentencing guidelines issued by the Sentencing Council are ‘offence specific’, providing a step-by-step framework for sentencing a particular offence or group of offences. For example, there is a guideline on Theft from a shop or stall and one on Dangerous driving. Where there is no relevant offence specific guideline, the General guideline: overarching principles provides a step-by-step process and information to help guide the sentencer instead.

The Council also produces ‘overarching’ guidelines, which address specific issues that may arise across many different offences. These include guidelines on Reduction in sentence for a guilty plea and Sentencing children and young people, which are expected to be used in conjunction with any relevant offence specific guidelines. The Overarching principles: domestic abuse guideline, hereafter referred to as the ‘domestic abuse guideline’, was issued by the Sentencing Council in 2018 and is another example of an overarching guideline. It applies to all sentencing courts in England and Wales. In accordance with the Sentencing Council’s statutory duties to assess the impact of guidelines in sentencing practice, and as part of its current strategic plan, Nottingham Trent University was commissioned to conduct a research review of the domestic abuse guideline. This explores the guideline’s impact on sentencing, as well as sentencers’ understanding, interpretation, implementation, and application of it.

2.1.1 Sentencing guidelines

Whether overarching or offence specific, all courts are legally obliged, by s59(1) Sentencing Act 2020, to “follow any sentencing guidelines which are relevant…unless the court is satisfied that it would be contrary to the interests of justice to do so.” Sentencing guidelines apply in magistrates’ courts, where (at the time of the research) sentences of up to six months’ imprisonment may be imposed for a single offence, and the Crown Court, where any sentence can be imposed up to the maximum legal sentence for the offence. The Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) also applies sentencing guidelines where these are relevant to the appeal.

Offence specific guidelines provide a tailored step-by-step process for the sentencer to follow, along with any relevant overarching guidelines. In summary, the process is as follows:

- Categorisation/provisional sentence

The court arrives at a provisional sentence based upon an initial assessment of the seriousness of the offence. This is determined by the culpability of the offender and the harm caused, intended to be caused, or that might foreseeably have been caused, by the offence. The outcome of this initial assessment is to arrive at a pre-determined sentence starting point and an associated category range as set out in the relevant guideline. For example, a given category may have a starting point of a ‘medium level community order’ and a range of ‘low level community order – 6 weeks custody’.

- Aggravating and mitigating factors

The court considers a non-exhaustive list of aggravating and mitigating factors in relation to the offence itself and the offender, including the offender’s criminal record or lack thereof. These factors can move a sentence up or down within the initial category’s range or, exceptionally, outside of the initial category.

- Reduction in sentence for guilty pleas

The court may reduce the sentence to reflect an offender’s guilty plea. Generally, the earlier the plea, the greater the sentence reduction. The court will refer to s73 Sentencing Act 2020 and the Reduction in sentence for a guilty plea overarching guideline to help decide precisely how much of a reduction to provide.

- Where applicable, there are further additional issues courts may take into account. These include:

- the court may reduce the sentence to reflect any assistance the offender has provided to the prosecution or investigators. For example, providing evidence or information implicating others involved

- an assessment of the ‘dangerousness’ of the offender to the public and whether special custodial sentences should be imposed

- totality – applicable when sentencing more than one offence and determining whether to impose sentences consecutively (served one after the other) or concurrently (served at the same time), to reach an overall sentence that is “just and proportionate”

- whether the offender should pay ‘compensation’ to the victim and any other ‘ancillary’ orders, such as a restraining order or disqualification from driving

- The court will then give reasons for, and explain the effect of, the final sentence.

With regards to the Council’s overarching guidelines, these do not follow a standard format or process. They are generally narrative guidelines that contain guidance on a range of cross-cutting areas that can be applied across a range of offences. Each one has been developed to meet the specific needs of sentencers in the area in question. The following section outlines the details of the domestic abuse guideline.

2.2 The domestic abuse guideline

In 2006, the Sentencing Guidelines Council (SGC), the predecessor body to the Sentencing Council, published the Overarching principles: domestic violence guideline. In 2018 the Council revised this guideline. The aim of this was to reflect important changes in terminology, expert thinking and societal attitudes. The Council intended for the revised guideline to ensure courts identify domestic abuse cases and factor it into sentencing decisions, and provide guidance on all the necessary information and factors to consider. The title of the guideline was changed to Overarching principles: domestic abuse, to reflect the fact that both physical violence and controlling behaviour can constitute domestic abuse. The guideline was further updated in 2021 to reflect the enactment of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, including that Act’s statutory definition of domestic abuse (discussed in detail below).

Although many criminal offences can involve domestic abuse, it is not an offence in its own right: in practice, conduct involving domestic abuse is often charged under other offence types, such as harassment, criminal damage, assaults or homicide. Indeed, some of the relevant offence specific guidelines for these offences contain reference to ‘domestic context’, for example as an aggravating factor. The Council also expects the principles of the domestic abuse guideline to be applied, in conjunction with any relevant offence specific guidelines, wherever an offence is committed in a domestic context.

The closest to a specific domestic abuse offence is Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship, under s76 Serious Crime Act 2015. An offence specific guideline for this offence was published in 2018 and is being evaluated separately to the domestic abuse guideline. This offence is therefore beyond the scope of this report and its evaluation will be published in due course.

The domestic abuse guideline is available on the Sentencing Council’s website, but a brief summary is provided below.

The guideline begins with a section on its scope, focusing on the definition of domestic abuse. This includes, but is not limited to, a summary of the detailed definition from the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (linked above). According to the Act, domestic abuse is abusive behaviour of person A against person B, where both persons are over the age of 16 years old and both persons are personally connected. Abusive behaviour can include physical or sexual abuse; violent or threatening behaviour; controlling or coercive behaviour; economic abuse; psychological, emotional, or other abuse. Person A and B are considered ‘personally connected’ when they are married; in a civil partnership; they have agreed to marry each other; they have agreed to become civil partners; they are, or have been, in an intimate personal relationship with each other; they have, or have previously had, a parental relationship with respect to the same child; or they are relatives.

This part of the guideline also reminds sentencers to avoid stereotypical assumptions regarding domestic abuse, noting that it “occurs amongst people of all ethnicities, sexualities, ages, disabilities, religion or beliefs, immigration status or socio-economic backgrounds”.

It then proceeds to emphasise that, “[t]he domestic context of the offending behaviour makes the offending more serious” and explains why. For example, “because it represents a violation of the trust and security that normally exists between people in an intimate or family relationship” and the likelihood of increasing frequency and severity. At this point, the guideline also notes that victim withdrawal from prosecution does not indicate a lack of seriousness and to avoid drawing any inferences from lack of victim involvement.

The guideline continues by listing some aggravating and mitigating factors “of particular relevance to offences committed in a domestic context”, for example, ‘Abuse of trust and abuse of power’, or ‘Evidence of genuine recognition of the need for change, and evidence of obtaining help or treatment to effect that change’, respectively. Some of these factors are incorporated into certain offence specific guidelines too.

The guideline then lists several other factors influencing sentence. These include some very general considerations in relation to victim wishes, the general irrelevance of provocation, the interests of children and the appropriateness of custodial sentences. There is also more specific guidance, on the application of statutory ‘dangerousness’ provisions and ancillary orders. The guideline concludes with information on the use of restraining orders and the relevance of victim personal statements made to the court.

2.3 The research review

This research review aims to provide an accurate and up-to-date indication of ‘practice on the ground’ to enable the Sentencing Council to consider the extent to which the domestic abuse guideline is delivering its aims and objectives. Its findings will supplement the extensive Overarching principles – Domestic abuse: Response to consultation (Sentencing Council, 2018a) and Overarching Principles – Domestic Abuse: Final resource assessment (Sentencing Council, 2018b) that were conducted by the Sentencing Council when the domestic abuse guideline was being drafted.

Resource assessments contain estimates of the potential consequences that the introduction or revision of a guideline may have on prison, probation, and youth justice resources. The assessments involve detailed analysis of current sentencing practice, alongside a review of current guidance, transcripts of judges’ sentencing remarks and news articles.

Following the consultation and resource assessment, it was anticipated that some sentencers might impose more severe sentences following the introduction of the guideline. This was due to the introduction of a principle in the guideline that cases committed in a domestic context should be treated more seriously than cases not committed in a domestic context. It was found that although some sentencers were already sentencing in line with this principle others were not, so it was estimated that there could be an increase in severity. However, it was not possible to predict the exact magnitude of any increase, or whether the guideline might lead to a change in the type of disposals sentencers handed down. Due to some emphasis in the new guideline on rehabilitation and the need to consider the most appropriate sentence to address the offending behaviour, it was also anticipated that some sentencers might give greater consideration to imposing a community order.

As noted above, the Council is required as part of its statutory duties to review the performance of its guidelines, and following public consultation in 2020, the Council identified five Strategic objectives for 2021-2026. These included a commitment to “explore the impact and implementation of the domestic abuse overarching guideline by undertaking an evaluation”. The Council therefore commissioned Nottingham Trent University in October 2023 to conduct a research review of the guideline.

This review focuses on:

- sentencers’ understanding, interpretation, implementation, application, and views about the guideline

- how the domestic abuse guideline is used in sentencing

- the impact of the domestic abuse guideline on sentences

As such, the key areas of focus here are the domestic abuse guideline’s effect on:

1. The decision on whether or not to categorise or classify an offence as one involving ‘domestic abuse’ or ‘domestic context’

How, if at all, does the domestic abuse guideline assist or affect sentencers’ understanding of domestic abuse? The guideline contains a large initial section explaining when it applies, including, although explicitly not limited to, the statutory definition of domestic abuse. We are interested in how, if at all, this and any other relevant parts of the guideline are used by sentencers to decide this question.

2. The sentencing process/decision

How or where does the guideline fit into the sentencing process and what parts of that process does it affect? For example, does it result in a change in the sentence starting point (in terms of assessing culpability or harm initially), or in an additional aggravating factor/s, later in the sentencing process? Similarly, does the guideline affect, for example, the use of ancillary orders or requirements?

3. The final sentence

Does the guideline result in a harsher, more lenient or different type of sentence? This could be in terms of sentence type: financial penalty, community order, or custodial sentence, or in terms of sentence severity: length of custodial period, number of hours of unpaid work, fine amount, and so on. It could be both. Relatedly, does the guideline result in the inclusion of a specific element to a sentence? For example, adding a particular rehabilitation programme to a suspended sentence order where one otherwise would not have been added, or favouring unpaid work over a curfew for a community order.

3. Methodology

In considering the questions outlined previously, the review draws upon both primary and secondary data, in particular:

- an anonymous online survey of sentencers with experience of sentencing cases involving domestic abuse

- one-to-one qualitative (semi-structured) interviews with sentencers which were anonymised post-interview

- a sample of transcribed Crown Court sentencing remarks (post-domestic abuse guideline implementation)

- reported and published Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) cases (post-domestic abuse guideline implementation), and

- data from previous Sentencing Council court data collection exercises (pre- and post- the domestic abuse guideline implementation)

Further details of each of these data are set out at 3.1 and 3.2 below.

Approval is required in order to conduct interviews or surveys with sentencers. This was obtained successfully following review of all research materials including interview and survey questions by both the Office of the Sentencing Council (OSC) and the Senior Presiding Judge (who acts as a point of liaison for judiciary and government). Nottingham Trent University’s Business, Law and Social Sciences independent research ethics committee also reviewed and approved the proposed programme of research and materials.

3.1 Primary data

3.1.1 Anonymous online survey of sentencers

A link to an online survey was disseminated to all sentencers in magistrates’ courts and all locations of the Crown Court via a link that was sent to their judicial email addresses. It was also posted on Magistrates’ Matters (a newsletter for magistrates) and the judicial intranet. Potential participants were informed of the aims of the review, as well as the other sources of data that would be relied upon alongside their survey. The survey was open from November 2023 to March 2024, with 365 responses received in total. Of those, seven were filtered out as the respondents had no experience of sentencing domestic abuse cases.

The survey consisted of closed and open questions. A closed question is one where the participant must select from a number of pre-determined options, for example ‘yes’ and ‘no’ or a four-level Likert-style scale (e.g. ‘very satisfied’, ‘satisfied’, ‘dissatisfied’, ‘very dissatisfied’). To encourage respondents to make a decision one way or the other, there were no ‘neutral’ responses (‘undecided’, ‘don’t know’, etc.). An open question is where participants write their own response, for example in a free text box after being asked to “please explain why”. The survey was designed to take around 10 minutes to complete, and it was made clear that “there are no mandatory questions, so you can skip any you do not want to answer”. A copy of the survey questions can be found at Annex A.

The breakdown of respondent roles is presented in Table 1, which shows that 85 per cent of respondents were magistrates, with those remaining being Crown Court judges (comprising circuit judges and recorders). The greater proportion of magistrate respondents is not surprising, given the national picture of sentencers. As of 1 April 2024, there were 14,576 magistrates (88 per cent), 127 district judges (magistrates’ courts) (< one per cent), 100 deputy district judges (magistrates’ courts) (<one per cent), 738 circuit judges (four per cent) and 988 recorders (six per cent) in post (Ministry of Justice, 2024).

Table 1: Survey respondent numbers broken down by judicial role

|

Judicial role |

Number |

% |

|

Magistrate |

305 |

85% |

|

Circuit judge (full-time salaried Crown Court judge) |

46 |

13% |

|

Recorder (a part-time Crown Court judge) |

7 |

2% |

|

Total |

358 |

100% |

Given the different roles and experiences of magistrates compared with Crown Court judges, we have distinguished these roles when reporting findings below. We have not distinguished between part-time (recorders) and full-time (circuit) Crown Court judges.

Responses to closed questions were analysed in JISC Surveys and via Excel. Responses to open questions were analysed and coded thematically. In this report, some of the free text responses have been edited for typographical errors and to promote clarity, but not where this would have affected respondents’ meaning.

3.1.2 Qualitative interviews with sentencers

Semi-structured interviews were designed to allow for more in-depth discussion than the survey and to allow for interviewees’ points to be elaborated upon and clarified in response to interviewer probing. The opportunity to be involved in one-to-one interviews was advertised to all sentencers in magistrates’ courts and all locations of the Crown Court via their judicial email addresses, the judicial intranet, Magistrates’ Matters (a newsletter for magistrates) and at the end of the survey. Information included a summary of the review and invited those interested in being interviewed to contact the research team. Those who responded were provided with a more detailed information sheet about the review and what their participation in an interview would involve, as well as a consent form. An initial recruitment target of 40 interviewees, split between jurisdictions (20 from magistrates’ courts and 20 from the Crown Court) was met. Interviews were conducted via video conferencing facilities between January and February 2024.

The interviews consisted of open questions in relation to the areas of focus outlined in section 2.3, as well as consideration of two vignettes (hypothetical scenarios) to stimulate discussions of how the domestic abuse guideline could apply within the interviewees’ decision-making processes. The first vignette involved an either-way offence (assault occasioning actual bodily harm (ABH)), which was used for all interviewees, as this type of offence can be dealt with by either a magistrates’ court or the Crown Court (hereafter ‘the ABH vignette (1)’). The second vignette involved an indictable-only offence (causing grievous bodily harm (GBH) with intent), which was used for Crown Court interviewees, as these types of offences can only be dealt with by the Crown Court (‘the GBH vignette (2)’). The third vignette involved a summary-only offence vignette (harassment), which was used for magistrates’ courts interviewees, as these offences can only be dealt with by a magistrates’ court (hereafter, ‘the harassment vignette (3)’).

A copy of the interview vignettes can be found at Annex B. The interviews were conducted by a member of the research team, recorded, professionally transcribed and anonymised. The anonymised transcripts were then analysed thematically by reading and noting key themes and sub-themes. Team members used NVIVO (software used to assist qualitative social science analysis) to record the relevant themes and sub-themes. In this report, some quotes have been edited slightly for clarity and to remove filler phrases (such as “you know” and “like”).

3.2 Secondary data

3.2.1 Transcripts of Crown Court sentencing remarks

A sample of 446 sets of transcripts of sentencing remarks from Crown Court cases post-2018 (after the domestic abuse guideline’s introduction) was obtained via the OSC, with the agreement of His Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS). The terms of this agreement stipulate that the cases referred to in the findings are not named.

These transcripts were selected from a ‘pool’ of transcripts held by the OSC. The sample provided by the Office to the research team was purposefully weighted towards those cases which were most likely to be relevant in terms of the time period (in other words, after the domestic abuse guideline) and offence type, and for those offences which the Council has produced guidelines for.

Each case was reviewed for the presence of potential domestic abuse or context by reference to the domestic abuse guideline’s definition (paragraphs one to seven). Only obviously irrelevant cases were removed, for example, where there was no connection between the offender and the victim, such as in the case of an assault on bar security staff. Fifty-five such cases were removed on this basis, leaving 413 for full analysis.

Table 2 outlines the types of offences contained in the sample of transcripts of sentencing remarks.

Table 2: Sentencing remarks sample numbers broken down by offence type

|

Offence |

Number |

|

Manslaughter |

137 |

|

Child cruelty offences |

40 |

|

Breach of a protective order |

39 |

|

False imprisonment |

25 |

|

Kidnap |

22 |

|

Racially and/or religiously aggravated harassment and/or stalking |

20 |

|

Threats to kill |

18 |

|

Stalking |

15 |

|

Modern slavery |

15 |

|

Blackmail |

14 |

|

Disclosing private sexual images |

13 |

|

Harassment |

13 |

|

Attempted murder |

12 |

|

Threatening to disclose private sexual images |

11 |

|

Bladed articles |

7 |

|

Witness intimidation |

6 |

|

Actual bodily harm |

3 |

|

Grievous bodily harm (s20) |

3 |

|

Total |

413 |

Relevant transcripts were imported into NVIVO for coding. NVIVO is a software package used to assist qualitative social science analysis, by recording and collating the themes and sub-themes identified by the user. The research team read and coded each transcript and then analysed them thematically. Thematic analysis (see Braun and Clarke, 2006) involves identifying general themes (or codes) and sub-themes (sub-codes) in order to draw conclusions from non-numerical data, such as documents and interview transcripts. Such codes may be derived from reading the data (for example, if a particular topic is mentioned in a set of sentencing remarks, this could then form a code) or may be agreed upon in advance as a factor to proactively consider. For example, if a factor is mentioned in the domestic abuse guideline, that might form a code. The team adopted a combination of the two approaches when analysing the sentencing transcripts.

3.2.2 Reported/published Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) cases

A systematic review was undertaken of all reported/published sentencing appeal judgments from the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) following the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline (from May 2018 to February 2024). This utilised the following legal databases: Westlaw, The National Archives’ ‘Find Caselaw’ service, BAILII (British and Irish Legal Information Institute) and Lexis+ UK. These results were narrowed down using the following search phrases:

- Overarching principles: Domestic Abuse

- Overarching principles AND Domestic Abuse

- Overarching principles AND Domestic Violence

- Principles AND Domestic Abuse

- Principles AND Domestic Violence

All judgments returned were then read and reviewed for relevance. This resulted in 42 relevant judgments, each of which were imported into NVIVO and analysed thematically, in the same manner as the sentencing remarks above.

3.2.3 Sentencing Council data collection exercises (pre- and post-domestic abuse guideline)

The Sentencing Council periodically conducts sentencing data collection exercises in both magistrates’ courts and the Crown Court. These are generally run for five or six months for selected offences. During data collection periods, sentencers are asked to fill out a short online survey immediately after passing sentence, with details about the sentencing outcome and the factors that were taken into account in reaching that outcome, as well as some information on the offender.

We drew on 12 data collections for this work. The collections for breach of a protective order, criminal damage, and harassment, all spanned periods prior to and after the introduction of new offence specific guidelines for these offences, as well as pre- and post- the domestic abuse guideline (Table 3). The other collections were conducted later than the introduction of the domestic abuse guideline but were included as they also collected information on whether the offence was committed in the domestic context and, if so, its impact on sentence (Table 4).

Table 3: Data collection periods by offence type, pre- and post-domestic abuse guideline

|

Offence type |

Data collection periods (pre-domestic abuse guideline) |

Data collection periods (post-domestic abuse guideline) |

|

Breach of a protective order |

01/11/17 – 30/03/18 |

23/04/19 – 30/09/19 |

|

Criminal damage |

01/11/17 – 30/03/18 |

04/01/21 – 07/05/21 |

|

Harassment |

01/11/17 – 30/03/18 |

23/04/19 – 30/09/19 |

Table 4: Data collection periods by offence, post-domestic abuse guideline only

|

Offence type |

Data collection periods (post-domestic abuse guideline only) |

|

Actual bodily harm |

04/01/21 – 07/05/21 and 09/01/23 – 30/06/23 |

|

Common assault |

04/01/21 – 07/05/21 and 09/01/23 – 30/06/23 |

|

Grievous bodily harm (s20) |

09/01/23 – 30/06/23 |

|

Grievous bodily harm with intent (s18) |

09/01/23 – 30/06/23 |

3.3 Limitations

The following limitations apply to each source of data and should be borne in mind when considering how representative or conclusive the review’s findings are.

3.3.1 Anonymous online survey of sentencers

While we secured our target number of participants, it should be underlined that the sample cannot be regarded as statistically representative. The Ministry of Justice reports that there are 14,576 magistrates in England and Wales and 1,953 sentencing judges (MoJ, 2024). In total, 305 magistrates and 53 Crown Court judges responded to the survey. Hence, this data is not representative of widespread sentencing practice or the views of the judiciary. It should also be noted that some sentencers did not complete every question in the survey, therefore data for some questions is incomplete.

We also depended upon participants volunteering, which carries a risk of self-selection bias. In other words, those inclined to volunteer their time for a research project on domestic abuse sentencing may be disproportionately more interested in or aware of this area of sentencing and associated issues, compared with the general cohort of sentencers sitting in criminal courts as a whole. Of course, this does have positives: it meant participants readily engaged with the survey questions and we received many helpful and highly relevant comments. However, it is important to be aware that such respondents may be differently inclined in terms of sentencing practice, use of the domestic abuse guideline, and so on, than the general cohort of sentencers.

3.3.2 Qualitative interviews with sentencers

The above limitations in relation to small and unrepresentative sample sizes likewise apply to the interviews as it was only possible to interview 20 magistrates’ court sentencers and 20 Crown Court sentencers. That said, this research did not aim to be representative of all sentencers. Rather, the interviews were designed to elicit a range of views on a topic through in-depth discussions, until data ‘saturation’ was reached (this is where fewer and fewer original findings and insights are found as more and more interviews (for example) are analysed, suggesting further ones are unnecessary).

Self-selection bias may also operate even more heavily here than in relation to the survey, given the extra time commitment required for an interview. Social desirability bias is also a risk with interviews. In other words, the natural tendency for people to tell researchers what they think they want or expect to hear. This is not necessarily deliberate and can operate subconsciously. It can lead to sanitised answers to questions, when compared with actual decision making in practice.

The use of vignettes also carries caveats. These were based upon the empirical research literature on the various ways that domestic abuse can take place and the team’s own criminal legal practice experience. As intended, this helped to move from abstract to practical discussions about the domestic abuse guideline. However, a real case would have much more detail and evidence, for example, photographs, statements, witness testimony, advocacy from both sides’ lawyer/s, and probation reports. The vignettes should not be considered (and were never intended to be) a ‘simulation’ of sentencing.

3.3.3 Transcripts of Crown Court sentencing remarks

As noted above (section 3.2.1), the transcripts included in this review were a sample from the ‘pool’ of transcripts held by the OSC. That pool is limited by the fact that it does not contain all the Crown Court sentencing transcripts for a particular offence, does not cover all types of criminal offences, and only covers those offences for which the Council has, or is, producing a guideline. It is possible therefore that there were offences potentially involving domestic abuse which we did not consider. Further, we analysed a total of 413 sets of remarks. Given that in recent years, the Crown Court has processed at least 20,000 cases per quarter (although not all of these will have involved domestic abuse) (MoJ, 2023), clearly this sample is not representative. In addition, it should be noted that these transcripts only cover the Crown Court as transcripts of sentencing remarks are not available for magistrates’ courts.

There is also a limitation in terms of what the transcripts can and do show. They show what a judge said on a particular day, with a particular audience in mind: offender, lawyers, victim, and so on. The transcripts also varied in terms of the detail they set out about the case. In some cases, they seemed to assume some prior knowledge and were quite unclear, perhaps because the detail would have been obvious to those involved in the case or due to time constraints. In other cases, remarks provided a clear and accessible explanation of the reasons behind a sentence. We could also not ask for clarification, or explore why the judge said something, or how precisely they used the domestic abuse guideline. Relatedly, if a judge had read or used the domestic abuse guideline to help with their sentencing decision in some way but had said nothing about it in their sentencing remarks, this would also not be picked up from analysing the transcript.

3.3.4 Reported/published Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) cases (post-domestic abuse guideline)

We are confident that all reported/published appeals cases were picked up within the period of analysis (May 2018 to February 2024). However, this does not mean that all appeal cases decided during that period of analysis will have been covered. Firstly, any cases decided during that period whose publication was delayed until after that period may have been missed. Secondly, while most appeal cases are reported/published, it is possible that a relevant case during this period may not have been, perhaps due to reporting restrictions imposed by the Court of Appeal pending a re-trial in the same case.

The only significant limitation is that this source covers a very small proportion of total sentencing exercises: only 42 relevant appeal cases were identified in the course of the previous six years. This will of course provide useful insights in those particular cases, especially on how the Court of Appeal viewed the initial sentencing decision. However, it does not give any indication as to how the domestic abuse guideline has been used or the effect it has had in the vast majority of cases sentenced in the Crown Court or the magistrates’ court which have neither been reported nor appealed.

3.3.5 Sentencing Council data collection exercises (pre- and post-domestic abuse guideline)

These surveys are completed in court, at the time of sentencing or immediately afterwards. In busy courts, it is possible that some sentencers might not complete the survey in full (or at all), therefore in some cases data for some questions (or sentences) may be missing.

In relation to domestic abuse in particular, while we were provided with data for the sentencing of seven different offences, these data were limited by the fact that only the collections for three of them, criminal damage, harassment and breach of a protective order, were available both prior to and after the implementation of the domestic abuse guideline. This makes it impossible to draw conclusions about the effect of the domestic abuse guideline in relation to the other four offences.

In relation to the three offences where this data was available, it is still difficult to show that any changes identified were caused by the domestic abuse guideline. For example, if domestic abuse was identified in more cases after the guideline compared to before, this could be because the guideline had improved sentencer awareness. However, it might equally have been because levels of domestic abuse may have risen during the same time period. There was also another key change to sentencing guidelines between these data collection exercises: new offence specific guidelines were introduced for all three of the offences. Hence, any observable differences might also be a result of those new guidelines rather than the new domestic abuse guideline. Lastly, the question format differed slightly between the pre- and post-domestic abuse guideline collections. The pre-domestic abuse guideline data collections asked sentencers “Broadly speaking, how did the domestic context affect your sentencing decision?” and utilised a dropdown list of responses, while the post-domestic abuse guideline data collections took one of two approaches. Those for criminal damage, actual bodily harm, common assault, grievous bodily harm and grievous bodily harm with intent asked that same question, but the list of dropdowns differed slightly, and for each option, a free text question was added, asking the sentencer to provide details as to why they had made that decision. Those for harassment and breach of a protective order asked an open question with a free text response: “In what way, if any, did the domestic context affect the final sentence and how?”. These differences in format and questioning may elicit different responses and reduce comparability.

3.3.6 Final comments on limitations

As mentioned above, all data sources have their inherent disadvantages. The fact that we have relied upon a variety of different sources of data and methods of data collection, mitigates some of these. For example, sentencing remarks demonstrate actual practice and so mitigate against the risk of social desirability bias presenting a sanitised account in interviews. Conversely, interviews allow sentencers to explain why they might do something and allows the researcher to ask clarifying questions, which is not possible when reviewing sentencing remarks. Surveys, due to their convenience, reach a larger group than interviews, providing a broader range of views. Sentencing Council data collections may provide less detail than some Crown Court sentencing remarks but cover a much greater number of cases and also include those from the magistrates’ courts (depending on the offence). Ultimately, the above caveats ought to be borne in mind when considering the findings. Nonetheless, despite these unavoidable limitations, these findings still provide helpful insight into the use of, and the perceived use of, the domestic abuse guideline across the criminal court system.

4. Findings

Across all sources of data, the following set of key themes was identified. This section is structured in accordance with these themes, rather than analysing each data source individually. All sources of data informed the findings and are discussed under each theme’s sub-heading, where relevant. Details of the vignettes used in the interviews with sentencers can be found at Annex B.

4.1 Sentencer views on when the guideline applies and what constitutes ‘the domestic context’

As noted in the introduction, one focus of this review was exploring sentencers’ understanding, interpretation, implementation, application, and thoughts about the domestic abuse guideline. A crucial part of that is sentencers’ understanding of whether the guideline applies at all. In other words, what is the ‘domestic context’ or ‘domestic abuse’?

As outlined in 2.2 above, the domestic abuse guideline itself is potentially applicable across a wide variety of circumstances where there is a ‘personal connection between the victim and offender. The Act also states that any child related to the abuser and/or victim, who “sees or hears, or experiences the effects of, the abuse” is also considered to be a victim of domestic abuse. However, the domestic abuse guideline is clear that it “applies (but is not limited to) cases which fall within the statutory definition” (emphasis added).

Across the data sources, there were many different ways in which the applicability of the domestic abuse guideline and the domestic context were interpreted. For some sentencers the domestic abuse guideline was welcome because it focused attention specifically on the domestic context as part of the overall crime, indicating that it needed to be taken more seriously than offences that had not been committed in a domestic context. Many sentencers stated that they did consider domestic abuse to be more serious than offences outside of the domestic setting and that the domestic abuse guideline had helped to solidify this view. It had also helped to challenge earlier stereotypical ideas about domestic abuse not being as serious as other types of offending, which otherwise might be prevalent. Such was the historic legacy of minimising the importance of domestic abuse that some interviewees and survey respondents, felt that even the word ‘domestic’ was inappropriate. For example:

Judge: It’s just got such connotations of 1970s policing, you know: ‘it’s [only] a domestic’.

The various approaches identified by this review as to whether the guideline is applicable are set out below. We begin with sentencers’ implicit or ‘common sense’ approach, before going on to consider approaches based upon the relationship, location and/or conduct.

4.1.1 The domestic context and applicability of the guideline is “just common sense”

Some sentencers appeared to use an instinctive common sense approach to whether a case fell within the definition of domestic context. In the case of magistrates, this appeared to be because many of them rarely used the domestic abuse guideline (see below, 4.2.1, and below, 4.2.4). Indeed, those magistrates who did turn to the domestic abuse guideline, often appeared (from interview and survey responses) to do so because they had some specialist interest in domestic abuse already – for example, from employment in social or healthcare professions or even personal experience. Of those surveyed, 32 per cent had sat in a specialist domestic abuse magistrates’ court.

Reliance on an implicit or common sense definition was also seen among judges and even occurred in some cases, when participants were guided specifically to or were asked in interview about the eight paragraphs under the relevant ‘Scope of the guideline’ heading. For example:

Judge: I can’t remember what the definition actually is [right now], but you know it when you see it.

Relatedly, as will be seen throughout the quotes from the interviews in this report, some sentencers appear to still be using the phrase ‘domestic violence’ rather than ‘domestic abuse’. Use of this term does not necessarily suggest a problem with sentencer understanding, but it does show how old terminology can become ingrained. Its continued use is contrary to the domestic abuse guideline’s aim to reflect important changes in terminology.

That said, generally judges stated in interview more often than magistrates that they used the guideline in order to decide whether the offence was in a domestic context. Some judges stated that they often began sentencing with the domestic abuse guideline, but the majority began with the offence specific guideline, before turning to the domestic abuse guideline for additional guidance and information.

It should also be noted that Crown Court interview participants tended to reference the guideline more frequently than was observed in the Crown Court transcripts. This could be a consequence of the fact that the guideline was the advertised subject matter of the interview, so it would be fresh in interviewees’ minds. It could also relate to social desirability bias in interview responses (the natural tendency for people to tell researchers what they think interviewers want or expect to hear), and/or to self-selection bias (those inclined to volunteer their time for a study on domestic abuse sentencing may be more likely to have awareness and/or interest in that topic than most). Equally, as we discuss further below (4.1.6), some judges may not always mention that they have used the guideline in their sentencing remarks, even if they have read or used it in the course of making their decision. Regardless of the cause though, there is a risk that even the reference from some judges in interviews to their using the guideline to help determine domestic context may present a slightly misleading picture of the frequency or level of the guideline’s use for this purpose compared with actual sentencing practice.

4.1.2 The domestic context and applicability of the guideline is relationship-based

Outside of the instinctive “you know it when you see it” approach, another way sentencers classified domestic abuse cases was on the basis of the nature of the relationship between the parties. This aligns with the part of the domestic abuse guideline (paragraph two), which lists some relationships (drawing on the Domestic Abuse Act’s definition). The most common example cited in this context from interview was a heterosexual relationship between (in accordance with the statutory definition) married or cohabiting couples with children, both in the abstract and in relation to the vignettes.

Magistrate: Well, it’s a family, they’re married.

Within this, some took a more detailed approach, examining the nature of that relationship, but still focused on that rather than the conduct.

Magistrate: It’s a domestic context because of the relationship between the offender and the victim. They’re married, they’re parents, they’ve lived together. So yeah, this is pretty clearly in [a] domestic context.

Magistrate: Oh, it’s not just the fact they’ve been married 15 years, it can also be partnerships for say six months, three months. You’re looking at the relationship between the two people as to whether you would consider it to be in a domestic context. And that takes into consideration for example, who might pay the bills, are there children involved? There’s a whole wide range of things that indicates a relationship, not just being married for 15 years.

Given that some of the vignettes involved a heterosexual married couple with children, picking up on this relationship was to be expected. The extent to which some focused exclusively on this aspect was notable though, given the many other things in the vignettes that might also have been relied upon (such as the conduct, see 4.1.5, below).

Beyond heterosexual couples with children, many magistrates and judges also gave other examples of relationships, including, for example, same-sex cohabiting couples, extended family members, or adult children and parents. The domestic abuse guideline was considered particularly useful by these sentencers for providing a wider range of relationships/examples that could fall under the domestic context.

Judge: Quite a lot of it is set out within the domestic abuse guideline, but basically, I look at it as any intimate relationship. Or that between partners. And, of course, whatever gender, sexuality is completely irrelevant and whether it’s parent, child, whatever it is, a familial or intimate personal relationship.

In the following quote, one judge emphasised a wide range of relationships, pointing to a key issue, that it was a relationship involving “trust”:

Judge: I try and broaden it as much as I can. It’s anybody who’s had a relationship of trust. Or something more than acquaintance. It’s a spectrum…I’ve done sentences recently where it’s been a stepson and stepfather arguing over other family members. So that’s probably a fairly tenuous link in that sense, but even step relationships can be close…. Offences that have happened between people who’ve been in a relationship that’s passed some time ago. There’s still that connection and a lot of the time the offence will be borne out of the circumstances or the breakdown of that relationship. So, it’s not just between husband and wife, [or] boyfriend, girlfriend.

Similarly, a magistrate interviewee emphasised the need for some kind of “bond” or “tie” and a level of “permanence”:

Magistrate: Now for me, to be in a domestic context, it’s about the level of bond and tie that is there, so my understanding of it would be that there was some level of permanence to that relationship and not to say that they’re still together or it has to be a really long time…. Intimate personal relationship means you’re to some extent sharing lives in a way that going on a few dates, you’re not.

This was particularly evident when it came to the harassment vignette (3, used in magistrates’ court interviews only). In that vignette, the connection between the parties involved “a few dates after meeting on Tinder”, before the victim said they did not want to pursue a long-term relationship. Many interviewees recognised that it was debateable whether this was a case of domestic abuse and used the domestic abuse guideline to help them decide one way or the other:

Magistrate: Well, I’m just trying to find exactly whether they’ve had an intimate or personal relationship. I suppose they’d been on a few dates. Would that be enough to argue that they had had an intimate, personal relationship? I think I would say, probably yes, but I can hear my colleagues, some of them would argue quite strongly against that. The fact that in the domestic abuse guideline, it doesn’t actually say how short or long that intimate personal relationship has had to have lasted to have been an impact. But then I can imagine [my colleagues would] start saying, ‘would one date mean that they’d had an intimate, personal relationship? … What about two dates?’ And you could get into that sort of difficult realm of, ‘how many dates?’ …and how do we know how intimate and personal they’d been in those dates and so on? So, it’s not straightforward.

Magistrate: Because the two people have been on a few dates, so that implies that a relationship is developing. We’re not told if there’s been any sort of sexual engagement, but that could be happening. A few dates, one of them already wants to pursue a long-term relationship. So, to me yes, I would say this would fall within the [domestic abuse] guideline.

Magistrate: No, I don’t know that it would [come within the domestic abuse guideline]…. It’s a different type of [relationship], the relationship is a different situation. It’s an early stage that [they] decided [they] didn’t want to pursue it.

Ultimately, in relation to the harassment vignette (3), some magistrates decided that it did and some that it did not count as ‘domestic’, but that could be due to the brevity of the vignettes, compared with what would be available in court. The important point for the purposes of this review is the assistance the domestic abuse guideline provides in such cases. Some, such as the first magistrate in the above example, pointed out the lack of guidance on relationship length. However, others considered that this was adequate, given the need to keep the guideline to a manageable length (see further, 4.2.4, below).

4.1.3 The domestic context and applicability of the guideline is location-based

A further way in which the phrase ‘domestic context’ was thought to apply was based on the location of the offence. The domestic abuse guideline and Act do not mention location (although the guideline does refer to a “household” in the context of different kinds of relationship), so this approach is unlikely to be drawing from them. The main locations focused on in the interviews were homes, often a “family” home:

Judge: This is violence of intimate partners, spouses, in the family home, I think.

However, other locations might include the homes of separated persons, for example where contact between the two took place incidentally, due to contact arrangements around children. The key thing for some was that this was a place where the parties lived, which could include extended family members rather than only intimate partners:

Judge: A domestic setting between people who are in a relationship of one sort or another, not necessarily an intimate relationship. And/or allied to people who have a relationship, within a family for instance, or something less than what we might think of as a family, but some sort of connection of a domestic nature between them.

In terms of location, for some sentencers, domestic context could be considered to include people living in shared accommodation without an intimate relationship in the traditional sense. Here some people could be within a domestic context, due to the nature of their living arrangements, rather than exclusively the nature of the relationship itself. As the judge in the following quote acknowledges, in some cases it will be the relationship within the location that is important; in others, the location itself determines the domestic context:

Judge: Or sharing the same household so it could be a landlord and his tenant for example, or cohabiting tenants. So ‘domestic’ how I understand it is being in a relationship or in circumstances in which you are in close proximity, such as sharing a flat. However, while location was important, some sentencers were of the opinion that this would require some kind of “quasi-domestic” relationship and behaviour outside of simple multiple-occupancy shared accommodation. For example, a degree of dependency or trust, reflecting the domestic abuse guideline’s reference to “expectation of mutual trust and security”.

In addition, being in a position of power was also considered:

Judge: If I had somebody who was living here as a friend. …let’s just say that they were a slightly weaker individual than me and I’m just more of a bully. …it’s different to some bloke in a pub who’s had too many beers and just smacks somebody. So, what is it? Instinct says ‘well, it’s quasi-domestic’ and therefore if that’s the case, although there’s no familial or sexual or intimate relationship, there’s still one person in a position of some degree of power over the other, and he’s abusing it, or indeed she’s abusing it. And if that’s right, then perhaps the guideline needs to specifically reference that scenario.

Although being in a position of power is not mentioned in the domestic abuse guideline’s definition of domestic abuse, ‘Abuse of trust and abuse of power’ is mentioned as one of the aggravating factors; paragraph four mentions ‘expectation of mutual trust and security’ and paragraph five mentions ‘acts designed to make a person subordinate’ in defining coercive behaviour. Text that focused on power and abuse of that power could therefore be worth considering for inclusion in the ‘Scope of the guideline’ section too.

That said, some sentencers indicated that they believed something more was needed than just living in a shared property with some position of power, trust, and/or dependency. Namely, a more intimate or familial type of relationship:

Judge: It wouldn’t, for example, include two students living together in student accommodation. It requires a more intimate relationship between the two. Doesn’t have to be formalised by marriage or something like that, and it would include stepchildren and fostered children and anything like that. But it requires that kind of relationship.

A location that appeared to be more problematic for sentencers was that of ‘virtual’ space. In particular, some magistrates struggled to decide whether the scenario in the aforementioned harassment vignette (3) should be regarded as domestic abuse. This involved a brief relationship between two parties and much of the harassing behaviour taking place online, albeit that the victim could well have been within their home when reading the online material. The brevity of the relationship, as noted previously, and the absence of cohabitation seemed to imply for some that this could not constitute a domestic context, whereas for others this was sufficient.

It may be that the domestic abuse guideline could clarify its applicability in virtual or online spaces (one way or the other) to encourage consistency of approach. Doing so would build on what is already considered by some to be a helpful role of the domestic abuse guideline. Many sentencers, particularly judges, felt that the sentencing guideline helped them to identify a range of domestic and familial relationships and to explain their decision about why it fell within the domestic context, and should therefore be taken more seriously by the court:

Judge: It can happen within the family. I’ve dealt with a case where a mother was being appallingly ill-treated by her son, and who in my judgement, fell very much within this overarching [domestic abuse] guideline. [The guideline] is a reminder and empowers the court to act in accordance with what I think is common sense. And justifies a robust and often severe approach to domination and control, and environments within that sort of context.

4.1.4 Problems with relying on relationship or location to determine ‘domestic context’

The reliance of many interviewees and survey respondents on the nature of the relationship, and/or location of the offence as the reason for classifying a case as involving domestic abuse, is somewhat contrary to recent caselaw. One such instance is R v Anthony Williams [2021] EWCA Crim 738, a case of voluntary manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility. In such cases the offender fulfils all the legal requirements for murder, but the partial defence of diminished responsibility applies. This requires an abnormality of mental functioning caused by a recognised medical condition, with the abnormality substantially impairing the individual’s ability to understand the nature of their conduct, form a rational judgement and/or exercise self-control. The abnormality of mental functioning must also have provided an explanation for the individual’s conduct in relation to the killing. On appeal against the sentence – which was in part based upon the fact that the judge failed to consider the domestic abuse guideline – the Court of Appeal concluded explicitly that the domestic abuse guideline did not apply in this case where the killing was perpetrated by (1) a husband against his wife and (2) in their home, because the case could not be properly classified as domestic abuse in the absence of a history of controlling or coercive behaviour, violence, or abuse. There was a similar logic expressed in a 2019 case from the Crown Court sentencing remarks sample, where the judge determined that the victim (the offender’s mother) being attacked in her home was not an aggravating feature, given that the case did not involve “persistent domestic violence but a one off push, which happens to have been in her home”. Such cases arose, notwithstanding that the 2018 version of the guideline referred to “any incident or pattern”. The updated version in 2022 has since clarified further that domestic abuse could arise through either “a single act or course of conduct”.

Secondly, in R v Dale Tarbox [2021] EWCA Crim 224, the Court of Appeal found that the guideline was not applicable on the following basis:

The circumstances of this case do not quite fit within the ambit of the domestic abuse guideline: although [victim] had stayed with Tarbox several times and for appreciable periods, and although there had been some sexual activity between them on at least two occasions, we do not think it can be said that they were or had been intimate partners or family members.